Adapted and condensed from “Comparaisons à Cannes,” translated by Jean-Luc Mengus, Trafic no. 19, été 1996. -– J.R.

In his introduction to Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan

records the consternation of one of his editors that “seventy-five

per cent of your material is new. A successful book cannot venture

to be more than ten per cent new.” From the vantage point of this year’s

Cannes Festival, a compulsion to contextualize everything new in

relation to something familiar reveals a comparable problem. Indeed, the

kind of movie pitch parodied at the beginning of Altman’s The Player,

in which every project becomes some version of one or two previous

hits — “The Graduate, Part 2,” “The Manchurian Candidate meets

Ghost” — has by now become a kind of journalistic shorthand for the

critic eager to make the film fully accessible once it’s released. This

necessity of establishing old references in relation to new ideas is above

all an indication of how thoroughly the priorities of the film business

have infiltrated film criticism.

As useful as this practice is, it often functions as a kind of nervous

tic. For the writer or speaker too lazy to perform the less alluring task

of description, it poses a constant temptation — a means of short-

circuiting the critical process through a kind of magic or alchemy that

suddenly makes the invisible visible. Being more guilty of this habit

than most, and finding it especially hard to avoid during the daily

pressures of Cannes, I’d like to attempt both a critique and an

autocritique of this tendency, hopefully indicating when it can serve

a useful critical function and when it simply interferes with critical

analysis.

To begin with an example that strikes me as being especially

dubious — a form of comparison that seems indistinguishable from

advertising — consider the following sentence from Janet Maslin in one of

her Cannes reports: “Set in Edinburgh (and already a big hit in

England), Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting is sure to prompt controversy as a

hip, clever provocation that’s raw enough to make Kids look like

Sesame Street.”

In point of fact, when Maslin calls Trainspotting “raw” she isn’t

referring to the film’s style, which holds relatively little interest for her,

but to her sense of the content, such as male frontal nudity and

excrement: “Tauntingly decadent, Trainspotting lets its drug-addicted

characters show off violent and grossly scatological behavior that will send

some viewers racing for the exits.” Stylistically, the film is actually

much less “raw” than the pseudo-documentary manner of Kids; it’s an

imaginative stylistic exercise that for me — to play my own version of the

comparison game — evokes Richard Lester in the early sixties in terms

of visual play and Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange in terms of narrative

form. In fact, these references occur to Maslin as well, but she couches

them again mainly in terms of puritanical class content: “Yet this

willfully outrageous film also has no trouble evoking either a grungier

Clockwork Orange or a ruder set of Beatles.” The Beatles are of course

the “product” being sold in A Hard Day’s Night and Help!; Lester is

only the film artist involved.

One reason for focusing on Maslin is that, thanks to her position,

she is the writer who has the most effect on which foreign films will

open in the United States and whether or not they will succeed

commercially. Yet the fact that she is clearly more interested in cinema as

a business than as an art, more fascinated by Harvey Weinstein than by

Kiarostami, Hou, or Godard, apparently places her in the majority —

which is why the circulations of the French and American Première

are higher than those of Cahiers du Cinéma, Positif, Trafic, Sight and

Sound, and Film Comment combined.

On the other hand, ten years ago, Première didn’t exist and Vincent

Canby, Maslin’s predecessor on The New York Times, was more

interested in art than in business. Did Première and Maslin suddenly come

along to “fill a need,” or did they, like so many of the movies they both

publicize, first manufacture the desire they now seek to exploit?

***

For me the principal pleasure afforded by Cannes is the

opportunity to take a two-week holiday from the so-called “fun” of

commercial American cinema, which tends to dominate the remainder

of my year. Perhaps this “fun” would feel less oppressive if it didn’t already

inform the experience in the United States of news, politics, fast food,

sports, economics, education, religion, and leisure in general, making it

less an escape than the very (enforced) essence of American life. A

bemusing paradox: after the alleged triumph of capitalism over Communism,

we find ourselves living in a “planned” culture that evokes in some

ways the Stalinism of the fifties, with Disney now assuming the

paternal role of the federal government, the spirit of Uncle Walt

supplanting the spirit of Uncle Joe. Within such a climate, the ideological

conformity of the press can seem no less claustrophobic, especially when

it comes to cultural references: during the last Christmas season, for

instance, I must have spent hours searching in vain for a single

American review of Oliver Stone’s overblown Nixon that failed to use the

adjective “Shakespearean.” The desire to dignify (and therefore sell)

political corruption with the nobility of classical culture seemed far

more important in this transaction than any desire to understand

Stone’s dramaturgy, and I would doubt that this impulse could be

plausibly linked to Luc Moullet’s effort in Cahiers du Cinéma in the fifties

to link Samuel Fuller to Christopher Marlowe.

In any case, one reason why Cannes offers an alternative to my

usual work is that most of the films shown here won’t open in Chicago

for another year. This is even true for certain American films if these

films are deemed “difficult” for the American public (which often

means politically threatening): last year’s Dead Man, for instance,

which has already had commercial runs in Melbourne, Lisbon, and

Istanbul, won’t reach Chicago until late June 1996. This means that I’ll

have plenty of time to test and reflect on my first reactions to most films

before I write about them at any length. (Perhaps only a few months for

those like Trainspotting and The Eighth Day that already have the

smell of money and hence Maslin’s interest; most likely more than a

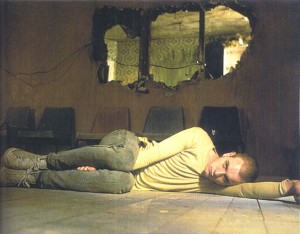

year for films like Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s Gabbeh and Hou Hsiao-

hsien’s Goodbye South, Goodbye that can be safely expected to have

neither.)

By now, I’ve developed such an automatic reflex of finding or

generating one cultural comparison per film at Cannes that I suspect it’s a

habit related to seeing several films per day, a convenient filing system.

In the case of Mike Leigh’s Secrets and Lies, the word “Ibsen” allows

me to organize certain observations I have about the film’s dramaturgy

and themes. But after I come out of Hou’s Goodbye South, Goodbye

with a certain sense of bewilderment — not knowing how to

contextualize this contemporary crime film in relation to Hou’s preceding

trilogy about the history of twentieth-century Taiwan — I feel that one

word from Marco Müller, director of the Locarno Film Festival, places

me on the right track: “Mahagonny.” Although I’ve never seen or read

Brecht’s opera, a constellation of elements in Hou’s film — elements

connected to the treatment of capitalism, the handling of music, the

episodic narrative, and even Hou’s exquisite sense of camera

placement — suddenly slide into focus. This comparison, however, may be

more useful to an occidental spectator like myself than to someone

from Taiwan. (By the same token, when I compare Râúl Ruiz’s

delightful Three Lives and Only One Death to late Buñuel — with Pascal

Bonitzer, Ruiz’s cowriter and “French connection” serving as the

counterpart to Jean-Claude Carrière — I conveniently ignore the fact that

Ruiz himself prefers Buñuel’s Mexican films.) Such a distinction may

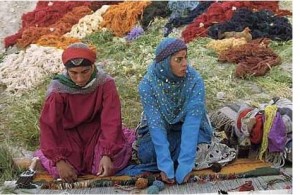

be less relevant when considering the very beautiful Gabbeh in

relation to Paradjanov’s The Color of Pomegranates, if only because it

appears that Makhmalbaf thought of this relationship long before I did.

One might argue, of course, that with these two films, the style is also

shaped by the subject matter — the poet Sayat Nova in the case of

Paradjanov, the nomadic tribes in southwestern Iran who specialize in

weaving gabbehs in the case of Makhmalbaf. But it is still fascinating

to discover that Gabbeh started out as a documentary and evolved into

a fiction film only gradually, because that appears to have been what

happened to Paradjanov’s film as well — suggesting that what

Makhmalbaf learned from Paradjanov was not only an attitude toward

space and color, but also an attitude toward subject matter.