From the Chicago Reader (April 25, 1997). — J.R.

Sling Blade

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Billy Bob Thornton

With Thornton, Dwight Yoakam, John Ritter, J.T. Walsh, Natalie Canerday, Lucas Black, James Hampton, Rick Dial, and Robert Duvall.

There is no point in rendering something realistically unless it is to make it more meaningful in an abstract sense. In this paradox lies the progress of the movies. — Andre Bazin

In one of the unfortunate casualties of film history and criticism, writer-director-performers are generally approached as performers and/or directors first and as writers second, yet it’s often the writerly impulse that gives birth to both the performance and the direction. Erich von Stroheim and Charlie Chaplin are seldom regarded as the writers of Foolish Wives and City Lights respectively, but without their scripts neither the performances nor the films themselves would exist. Orson Welles, habitually described as a director and actor, insisted throughout his career that he always started with the written word, not with free-floating ideas for “shots.”

So it was a matter of some satisfaction to me that Billy Bob Thornton wound up getting an Oscar last month not for his lead performance in Sling Blade or for its direction but for his script. Though he reportedly invented the character of Karl before he ever sat down at a typewriter — by making faces in a mirror during a lunch break while performing a small role in someone else’s picture — it was his writing that made sense of the character. His directing did little but arrange and highlight the insights he arrived at through writing. (Thornton’s mise en scene is mainly a matter of no-nonsense camera placement and nuanced lighting — a strictly functional approach that’s rare these days, when most scripts are too mucked up with different people’s agendas to allow a straightforward treatment.)

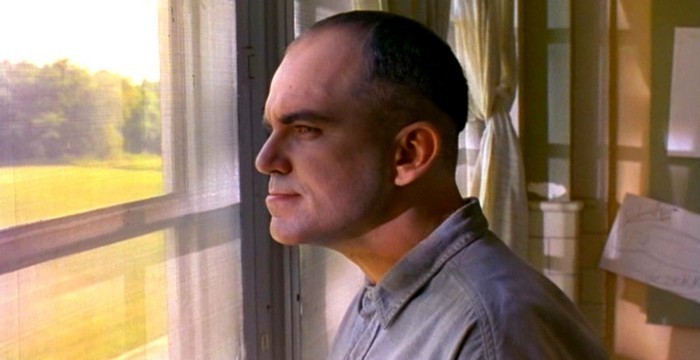

Strictly speaking, the world of Sling Blade is realistic — especially to an erstwhile southerner like me — but it might be argued that Karl, played by Thornton, is by far that world’s least realistic element. Defined at the outset as a simpleton and regarded by most of the other characters as retarded, at the age of 12 he murdered his mother and her young lover, then was committed to a mental hospital for 20-odd years. Yet the character seems to derive less from clinical studies of the criminally insane or the “mentally challenged” than from a few intuitive thoughts about simplicity as a moral concept. (A friend of mine who’s worked professionally with the retarded and who likes Sling Blade regards Karl as a fantasy about such people, not as an accurate portrayal.)

Dropped into the middle of a southern backwater populated by densely realized, fully recognizable individuals, Karl is a minimalist construction: morally and dramatically, he functions as a catalyst on this world when he’s released from the hospital shortly after the film begins. Thornton may deserve the attention he’s received for his performance as Karl, but as writer he’s assigned himself none of the familiarity or readability of the other characters. Yet we’re mesmerized by him, despite his minimal affect, because we’re never sure what he’ll do next; it takes the entire film to explain who he is, and by the time we learn, we’ve lived through a kind of moral suspense that also informs our knowledge.

Much of this moral suspense derives from how we and the other characters in the film respond to Karl, and how we respond to other people’s responses. In fact, most of the characters approach him with a certain goodwill and charity: a hospital administrator who finds him a job fixing lawn mowers (after taking him in for a night); his boss and coworker at the repair shop; a little boy named Frank (Lucas Black), whom Karl instantly befriends; Frank’s mother Linda (Natalie Canerday), who works as a clerk at a nearby dollar store and who invites Karl to stay in her garage; and Linda’s best friend Vaughan (John Ritter), a homosexual who works as her manager and who regards Linda and Frank as his only family.

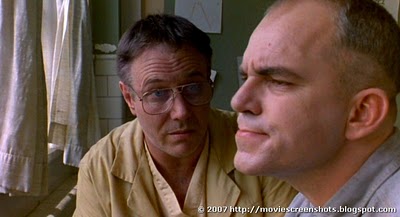

Notably less charitable are Linda’s violent alcoholic boyfriend Doyle (Dwight Yoakam), who runs a local construction company, abuses Linda, and dislikes Frank, Vaughan, and Karl with equal intensity, and Karl’s father (Robert Duvall), an alcoholic sawmill worker who appears in only one scene but whose former meanness and destructiveness are recounted at some length. A couple of the featured characters are too limited to dispense much charity: Charles (J.T. Walsh), a sexual offender and Karl’s fellow patient at the hospital, who regales Karl with stories of his sexual exploits, and Melinda (Christy Ward), another simpleton whom Linda and Vaughan briefly try to set Karl up with.

The film’s first extended speech is Karl’s account of the double murder he committed as a boy, given to a journalism student in a dimly lit classroom. This is the first time that we see Karl — whose eccentric, evocative behavior includes a droning delivery punctuated by singsong hums — reverberate against the world outside the hospital. (An earlier performance of this monologue, directed as a short by George Hickenlooper, gave Thornton a sample reel to raise money for Sling Blade.) Karl recounts a tale of mistreatment and cruelty, first by his parents, who forced him to live in a floorless shed behind their house, and then by his classmates at school — including Jesse, the son of his father’s boss, whose bullying led Karl to drop out. Hearing noise in his parents’ house one day, Karl stumbled upon his mother and Jesse having sex on the floor, and with a blunt instrument (“Some folks call it a sling blade, I call it a kaiser blade”) murdered first Jesse, then his angry mother. Asked by the journalism student if he’d ever kill anyone again, Karl intones, “I reckon I got no reason to kill nobody.” (Viewers who don’t want the plot of Sling Blade divulged should check out here.)

This speech provides the bulk of what we know about Karl’s childhood, except for an incident he recounts much later to Frank: when Karl was only “six or eight,” his father handed him a bloody towel containing a premature baby, still alive, and told him to throw his brother away. Barely aware of what was happening, Karl wound up burying him in a shoebox. One doesn’t have to be much of a Freudian in order to see Karl’s double murder at age 12 as an Oedipal act with Jesse standing in for his father, and his bonding with Frank as a search for a kid brother to replace the one he buried. Shortly after recounting this story to Frank, Karl pays a brief visit to his father that makes both these scenarios fairly clear: his monosyllabic conversation with his dad includes the line “I’m your oldest boy, name of Karl,” and immediately afterward he visits the “grave” of his dead brother. It’s equally clear that Doyle is a surrogate for Karl’s father; Thornton emphasizes the point by framing the two of them almost identically when each is in an alcoholic haze of self-loathing. So when Karl winds up killing Doyle with a lawn-mower blade in order to protect Frank, he’s acting out the same Oedipal scenario that sent him to the mental hospital in the first place.

For Thornton, however, the moral difference between these two acts of murder is crucial: the first is the result of blind rage and confusion, the second a considered and methodical step taken to protect what Karl values most in the world — a step taken, moreover, with the apparent eerie complicity and consent of the victim. (Doyle even furnishes Karl in advance with precise information about how to phone the police.) And this moral distinction — further highlighted by Karl’s acceptance of Vaughan as a suitable father for Frank despite biblical injunctions against homosexuality — indicates that Thornton considers Sling Blade not as any kind of criminal case study but as an ironic parable about goodness.

Eight months have passed since my first look at Sling Blade; I made a recent, post-Oscar return visit at Pipers Alley. Thanks to the usual meddling of Miramax, the film’s been cut by nine minutes in the interim, and though I can’t pinpoint any of the losses after this long interval, I can’t really say that tightening up the narrative feels like an improvement. A slow, contemplative film in both versions whose strong suit is its utter lack of adornment, Sling Blade needs a lot of space to register its points, and whatever streamlining it’s received as narrative has deprived the audience of some of the time needed to reflect on it.

Several weeks back a sympathetic but distressed reader wrote to me about my favorable capsule review of Sling Blade; she found the film sick and misogynistic and Karl just another version of Forrest Gump, urging me to see the film again and reevaluate it, particularly in light of its sexual politics. It’s true that Sling Blade is light-years away from political correctness, but it still strikes me as having something meaningful, nuanced, and even religious to say about goodness, pertaining to women as well as men — and its morality does not simply rely on justifying murder. At first I connected the film with William Faulkner — specifically, the resignation of the nameless convict returning to prison at the end of The Wild Palms. But after a second look I’m reminded more of Flannery O’Connor, a religious writer well known for her appalling, hard-as-nails irony. In her great short story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” a mass murderer called the Misfit speaks this climactic line: “She would of been a good woman…if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” Perhaps even more to the point is the last line of O’Connor’s preface to Wise Blood, her first novel: “Freedom cannot be conceived simply. It is a mystery and one which a novel, even a comic novel, can only be asked to deepen.”

It’s not the real world that’s at the heart of Sling Blade but an abstract sense of mystery that comes from reflecting on freedom within that world. Karl is a means of arriving at that abstraction and mystery. But within the real world, Thornton considers the separate plights of many people: a generous single mother saddled with a brute, a little boy whose father was driven by failure to commit suicide, a gay man whose emotional attachments make it impossible for him to leave an intolerant backwater, and even a brute who seesaws relentlessly and helplessly between abuse and apology. Like Karl, these people have only a narrow range of choices, but Thornton looks at their efforts to cope — that is, at their freedom — with a great deal of understanding and generosity. And like O’Connor’s vision, his is most terrifying and appalling because he conceives and expresses it in comic terms.

Sometimes the comedy comes simply from Karl trying to imitate or accommodate himself to the world: when he tries to repeat an obscure joke he’s heard at the repair shop to Linda, the wonder isn’t that he gets it wrong but to what degree he gets it right. And sometimes the comedy comes from the deepest kind of philosophical insight: when Charles, Karl’s fellow patient and inmate, asks him at the end of the film how he found the world outside, Karl’s reply is simply, “It was too big.”