From the Chicago Reader (March 25, 1994). — J.R.

*** SAVAGE NIGHTS

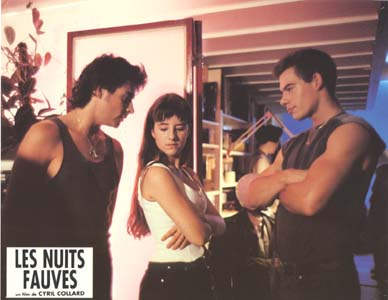

Directed by Cyril Collard

Written by Collard and Jacques Fieschi

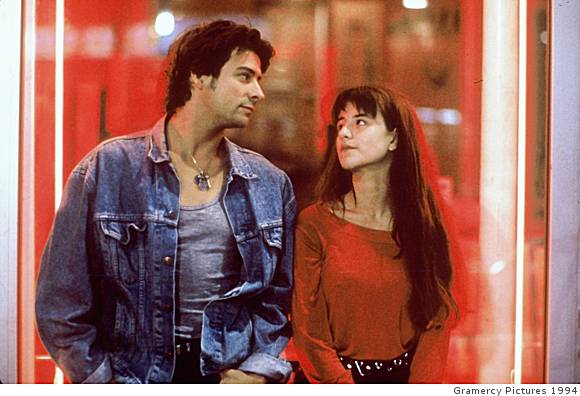

With Collard, Romane Bohringer, Carlos Lopez, Corine Blue, Claude Winter, Denis D’Archangelo, and Jean-Jacques Jauffret.

If memory serves, the first time I ever heard of Sylvia Plath was the first time a lot of other people heard of her — in the mid-60s, a few years after she committed suicide, when her posthumous collection Ariel was published. I recall a teacher of mine in graduate school remarking that Plath’s suicide validated her late poetry, implying that if she hadn’t actually taken her own life, poems such as “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy” wouldn’t have meant as much as they did — indeed, may not even have been “as good.”

The remark offended me at the time, but in retrospect I wonder if in some awful, seldom-acknowledged way my teacher was right. Many of us prefer to believe that works of art should be self-justifying, and therefore demand to be taken on their own terms, without “outside” information, but the fact remains that the hyperactive media and life itself rarely offer us that luxury. Take, for instance, these two consecutive stanzas in “Lady Lazarus” — “Dying / Is an art, like everything else. / I do it exceptionally well. . . . I do it so it feels like hell. / I do it so it feels real. / I guess you could say I’ve a call.” There’s a world of difference between reading these lines with the knowledge that Plath had already attempted suicide once and would try again and succeed and reading these lines without that knowledge. Without it the lines themselves, for all their blunt strength, don’t have the same impact; they might even sound self-indulgent.

A related quandary presents itself with Savage Nights (an adequate though incomplete translation of the original French title, Les nuits fauves), written by, partially scored by, directed by, and starring a bisexual musician/composer/filmmaker who died of AIDS a little more than a year ago. Because it deals semiautobiographically with the reckless life-style of the filmmaker, Cyril Collard, presumably before as well as after he learned he was HIV-positive, it is not a movie that can be approached from any neutral corner. The relation of life to art was undoubtedly even more melodramatic for a French audience because Collard, who was one of the first public figures in France to openly acknowledge being HIV-positive, was still alive when his film opened in France. In fact, he died only three days before Savage Nights swept the annual Cesar awards (the French equivalent of the Oscars), winning prizes for best film, best first film, best editing, and best new actress (Romane Bohringer), and it seems likely that given the circumstances under which they were awarded, the prizes had some political import.

Even in the U.S., where the political significance of the film is necessarily somewhat different, we can’t ignore the film’s autobiographical subtext; and the fact that Collard is now dead may intimidate us into not being too critical — even if we wind up recoiling from the movie, as some people have.

Conceived and executed as an act of defiance, Savage Nights virtually defines the cliched buzz term “in your face” by confronting the viewer with a good many things that are missing from most other contemporary movies and, more defiantly still, refusing to pass judgment on almost anything. For starters, though none of its characters seem especially bright or talented, they all seem to be living in the real world. Collard gets this across with a series of shocks — shocks that are the movie’s strengths as well as its limitations, that define its style as well as its content.

First a bit about content, which in this case means the plot. (If you don’t want to hear about it, skip to the next section.) Adapted from Collard’s novel of the same title — published in French in 1989 and in English quite recently — Savage Nights is mainly devoted to a few months in the life of Jean, a 30-year-old cinematographer and musician with AIDS living in Paris in 1986. After testing a 17-year-old girl named Laura (Romane Bohringer) for a part in a TV commercial that she doesn’t get, he calls her up, expresses his attraction to her, and before long has sex with her without telling her he’s HIV-positive. When he finally confesses this fact to her some time later, her anger is succeeded by an infatuated desire to remain with him and, less rationally, to “save” him with her love, and she insists on having further sex with him without a condom.

Far from being monogamous, Jean periodically looks for and finds anonymous sex — including group sex, hand jobs, and “golden showers” — with men along the banks of the Seine. He also becomes sexually involved with a taciturn, punkish youth named Samy (Carlos Lopez), whose Dutch father is in prison and whose Spanish mother used to work as a part-time prostitute. Through the influence of a fascistic pimp named Pierre Ollivier (Jean-Jacques Jauffret), Samy hangs out with skinheads and becomes increasingly drawn to sadomasochism. Samy is living with a woman when he first meets Jean, but after a spell, to the consternation and anguish of Laura as well as his former lover, he decides to move in with Jean. Samy also expresses a desire to have unprotected sex with him, but in this case Jean refuses, and he also declines sex of any kind with his ex-girlfriend Karine (Laura Favali).

Seemingly appalled by the morbidness and possessiveness of Laura’s continuing infatuation with him, Jean refuses to respond to most of her phone messages until she has a nervous breakdown; then he helps her mother take her to a sanitarium. Several weeks or months later he goes to visit Laura, now recovered, at a seaside location (possibly near her grandmother’s home in Nice, though this isn’t spelled out); he tells her he loves her, but she informs him it’s too late. Looking up Samy in Spain, who’s now fully under the influence of Ollivier, he saves a skinhead from castration in a gang skirmish by cutting his own hand with a knife and threatening to infect Ollivier if the boy isn’t spared. Still later, he travels alone to another seaside location — again unspecified, but described by him as “the edge of Europe,” which probably means the southern tip of Spain or Portugal — and phones Laura, telling her in essence that by facing death he’s finally come to understand life and caring for other people.

The most obvious attributes of the film’s style are a camera that tends to remain close to the characters and mobile (reportedly the camera was most often mounted on one of the shoulders of the cinematographer, Manuel Teran) and editing that depends largely on jump cuts — unexpected breaks in continuity and leaps forward in the action. Less prominent, though worthy of mention, is an emphasis on bright colors that, according to Collard in a 1992 interview, stems directly from a desire to emulate fauvism, the artistic movement associated with such painters as Matisse, Derain, and Vlaminck. (This style point is one reason “savage nights” is a less-than-perfect equivalent to les nuits fauves.)

What seems most significant about the camera and editing styles is the way they play against one another (as in Godard’s Breathless, which also features jump cuts and a mobile, hand-held camera kept close to the characters). From one point of view, the “hot” camera pulls us into the thick of the action while the “cool” editing distances us, skipping across consecutive events like a pebble skipping across the still surface of a pond, never giving us enough time to invest ourselves fully in the elements of a given scene; thus the very rhythm of the film becomes a kind of existential stammer. But one can also interpret this pattern in the opposite way: the camera’s closeness to Jean, Laura, and Samy — all of whom behave recklessly and often hysterically, and who in many important ways can be regarded as three versions or aspects of the same character — alienates us from their compulsive behavior, while the jump-cutting energizes us, repeatedly pushing us forward in a manner that forces us to share their compulsiveness.

Whatever interpretation one chooses, the net result is the same: an objectivity toward the characters. Our relationship to them is neither wholly empathetic nor wholly critical. The fact that Collard forces us to reach our own conclusions about them is the film’s biggest challenge, its ultimate dare — and what prevents the movie from being a soporific Hollywood “entertainment.”

How “pure” is Jean’s bisexuality? When he has sex with Laura before telling her he’s HIV-positive, and when he later refuses to pick up the phone when she calls repeatedly, leaving frantic messages — some of which he plays back later in his car — is this because he unconsciously hates her? The film doesn’t conclusively support or deny this idea; we have to decide for ourselves. Nothing the movie tells us is privileged, not even Jean’s offscreen narration — though this fact may wind up partly contradicting Collard’s intentions.

The weakest parts of the movie are the beginning and the end, perhaps because these parts break with the stylistic dialectic described above and grapple toward final definitions of some sort. In the prologue, set in Morocco in March 1986, Jean has a brief, enigmatic encounter with a woman named Noria, played by Maria Schneider, the lead actress in Last Tango in Paris. Schneider seems to be turning up as a muse to bestow her benediction on the film; she also appears later in a dream. Meanwhile Jean informs us offscreen that his astrological sign is Sagittarius. It all smacks of new-age mumbo-jumbo and hopeful invocation, including the scene just afterward when Jean arrives in Paris a month later and tells us he’s just learned about the death of Jean Genet. This whole patch of the movie feels like a string of quotations attached to the beginning of a novel, and the ending isn’t much clearer, even though it’s aiming even more obviously for transcendence or some notion of the infinite. Chicago film critic Sergio Mims persuasively compares it to the ending of The Incredible Shrinking Man — which I suppose, in a way, Collard is at this point, although the narration would have us believe that he’s expanding (“Perhaps I’ll die of AIDS . . . but I’m part of life”). Maybe, according to Collard’s philosophy, he’s doing both, rather like the incredible shrinking man entering the infinite molecular universe.

I have fewer problems with what comes between the beginning and the end, even though the three central characters aren’t very likable, behave monstrously on occasion, and are sometimes impenetrable (Samy in particular). After all, the same could be said of most of the characters in King Lear — which is not to suggest that Collard has much else in common with Shakespeare. (Some critics have complained that the way the characters scream at one another in some scenes points to some dramatic failing on Collard’s part, but I can’t see what they’re talking about. The consequences of playing out one’s feelings to the utmost, sexual and otherwise, are the subject of this movie, and Collard needs those screams the way Matisse needed those blues — all the better to splash us with.)

These characters don’t ask for our approval, not even once, and they ask more from life than it’s fashionable to want. If they cleaned up their acts, they’d bore us to distraction — which is probably why the ending, by which point Laura and Jean have allegedly straightened out a bit, fails to interest us much. They’ve become too much like characters in other movies.

How much of the movie is fiction and how much is documentary? It doesn’t linger over clinical details, but when we see Jean being treated for a lesion it doesn’t look fake. Collard, by the way, wound up playing the lead part only as a last resort, when he couldn’t find anyone else who was both suitable and willing. Considering everything else he does — including singing seven of the songs on the sound track, four of which he wrote or cowrote — it’s amazing that he can pull it off. But he does.

When I first saw Savage Nights, several weeks ago, I wasn’t sure what I thought; but it sure woke me from the living death most Hollywood entertainments offer nowadays to anyone looking for more than simple diversion. Now that I’ve seen it again, I still can’t say that I like all of it, but I also still find it difficult to dismiss.

People who come out of Philadelphia feeling the least bit irritated should rush off to Savage Nights without delay; if there was ever a corrective to that Hollywood snow job this is surely it, and a movie this blunt and honest doesn’t usually stick around for long. No bad courtroom drama here, no sucking up to “likable,” down-home homophobes, no nice-guy speeches, no role models. Just three desperate, largely interchangeable people going for broke, going under, sometimes going over the top, and going after their desires like insane fiends, whether we like it or not.