From the May 20, 1988 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

BABETTE’S FEAST

** (Worth seeing)

Directed and written by Gabriel Axel

With Stephane Audran, Jean-Philippe Lafont, Gudmar Wivesson, Jarl Kulle, Hanne Stensgard, Bodil Kjer, Vibeke Hastrup, and Birgitte Federspiel.

Only when she had lost what had constituted her life, her home in Africa and her lover, when she had returned home to Rungstedlund a complete “failure” with nothing in her hands except grief and sorrow and memories, did she be come the artist and the “success” she never would have become otherwise — “God loves a joke,” and divine jokes, as the Greeks knew so well, are often cruel ones. What she then did was unique in contemporary literature though it could be matched by certain nineteenth century writers — Heinrich Kleist’s anecdotes and short stories and some tales of Johann Peter Hebel, especially Unverhofftes Wiedersehen come to mind. Eudora Welty has defined it definitively in one short sentence of utter precision: “Of a story she made an essence; of the essence she made an elixir; and of the elixir she began once more to compound the story.” — Hannah Arendt on Isak Dinesen

When Ernest Hemingway accepted his Nobel prize in 1954, he was gracious enough to acknowledge that it should have gone to Isak Dinesen instead. Yet the fact that two adaptations of her work have recently become box-office hits strikes me as something of a mixed blessing, if only because of certain essential elements of Dinesen that get shaved away in the process. Admittedly, the two films don’t belong in the same class; after Out of Africa, a star vehicle with pretty scenery (an even soggier reduction than the movie of Sophie’s Choice), Gabriel Axel’s film, Babette’s Feast, is a model of tact, intelligence, proportion, and scale. But it’s still many rungs below Dinesen, despite several claims to the contrary.

Some of my misgivings are out-and-out biases, and in order to enable readers to make allowances for them accordingly, I’ve decided to place them in a section devoted to other gripes, which I’ll get to only after disposing of what I like about the film.

What I like about Babette’s Feast:

It won the recent Academy Award for best foreign-language film. Its leading rival, moreover, was the more platitudinous Au revoir, les enfants – a star vehicle in its own right, but the star in this case was writer-director Louis Malle’s offscreen gilt-edged guilt.

As story telling, Axel’s filmmaking is economical, fluid, and graceful. The decisions about what to illustrate and/or expand upon from the original (which was first published in Ladies Home Journal) are far from obvious or mechanical; they frequently reflect the sort of unexpected slants and elaborations that one might expect to find in imaginative book illustrations. Consider, for example, the lengthy flashback in which the prospective suitors of two devout Lutheran sisters, Martina (Vibeke Hastrup) and Philippa (Hanne Stensgard), both depart. A young soldier named Lorens (Gudmar Wivesson) briefly makes eyes at Martina, makes a passionate declaration to her, then leaves for good. Axel seals Martina’s memory of him in an understated exchange between the sisters at bedtime: “Do you remember that silent young soldier?” “Yes.” As for the departure of a French singer named Achille Papin (Jean-Philippe Lafont) who became smitten with Philippa while giving her music lessons — a portly and somewhat comic figure in the movie, if not in the story — Axel gives us a mock-solemn shot of Papin being rowed away, in comic-opera splendor, to illustrate Dinesen’s line, “Achille Papin took the first boat from Berlevaag.”

Perhaps the most striking and original of Axel’s narrative niceties is using a woman’s voice for the impersonal third-person narration. The unseen, “objective,” and all-knowing male voice is usually an unconsidered cliche in films of this kind. While the impersonal narrative voices in Dinesen’s tales are most often androgynous, it might be argued that the voice in “Babette’s Feast” is more distinctly feminine. Whether it is or not, it’s refreshing to find this deviation from the monotony of the usual patriarchal authority on the sound track — the same sort of unseen male God who addresses women from the great beyond in most TV commercials.

Considering the fact that Axel, Dinesen, and Babette’s Feast are all Danish, it’s understandable that the setting of the story has been shifted from the Norway of the original to Denmark, and that though the story was written in English, it has been likewise translated to Danish. When the leading character, Babette (Stephane Audran), appears — a French Communard in flight from persecution in Paris — the sisters speak French with her until she learns Danish better, and the mix of these two languages is a nice substitute for the exclusive English (apart from a few French terms) of the original. Gabriel Axel lives in Paris, so the linguistic juxtapositions are undoubtedly second nature to him; but they also help flesh out certain details that Dinesen was more sparing about, such as the gradual adjustment of Babette — who turns up on the sisters’ doorstep bearing a letter from Achille Papin and becomes their servant — to a foreign culture.

Finally, the acting of Babette’s Feast is more or less impeccable; the all-star Scandinavian cast includes seasoned veterans of Dreyer, Sjoberg, and Bergman as well as Stephane Audran, who is probably remembered best for her roles in Bunuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and countless Chabrol movies. On top of this, the performances tend to be competent without qualifying as “star turns” (except for a showy bit by Bibi Andersson) — the kind of showboating that one usually expects from Oscar winners, where showy effects often count for more than believable characters.

What I don’t like about Babette’s Feast:

It won the recent Academy Award for the best foreign-language film. The fact that it beat out Au revoir, les enfants counts for little beside the fact that a number of better foreign-language films — including The Horse Thief, Melo, Homecoming, The Jester, Mammame, Life Is a Dream, Tampopo, The Legend of Suram Fortress, Repentance, The Theme, and El sur — weren’t even nominated. Although I don’t share the bias of some of my colleagues that The Last Emperor is somehow tainted by its own Oscar, it seems to me less than a coincidence that the winner in the foreign slot should be oriented toward the Masterpiece Theatre notion of excellence: slick, tasteful, formally unadventurous, politically uncontroversial.

Compare the opening sentences of the story with the first two shots of the movie and you already get some notion of the kind of genteel reduction involved; in place of what might be regarded as Dinesen’s French Impressionism, Axel offers pretty picture postcards. Dinesen: “In Norway there is a fjord — a long narrow arm of the sea between tall mountains — named Berlevaag Fjord. At the foot of the mountains the small town of Berlevaag looks like a child’s toy-town of little wooden pieces painted gray, yellow, pink and many other colors.” Axel: Long shot of distant farmhouse with smoking chimneys; the camera pulls back slowly. Cut to a much closer shot that pans down hanging fish while offscreen piano music is heard.

If we accept the notion that much of Dinesen’s power comes from her use of language, then the film, which drastically reduces that language and translates it into Danish, has to be something less. When young Lorens, the soldier, discovers his feelings for Martina, Dinesen treats this discovery in one magisterial sentence: “At this one moment there rose before his eyes a sudden, mighty vision of a higher and purer life, with no creditors, dunning letters or parental lectures, with no secret, unpleasant pangs of conscience and with a gentle, golden-haired angel to guide and reward him.” After a single viewing, I can’t be sure whether Axel uses some, most, or all of that sentence, but the overall impression left, which is what counts, is something much briefer and simpler.

One has to acknowledge, of course, that film and literature, being different in their essences, can’t be expected to duplicate the same effects. There are times, however, when Axel’s license gives his own effects a cuteness and/or a glibness that one would never find in the story. When Lorens is sent to the country by his father, which leads to his first encounters with Martina, Dinesen simply tells us that he has run up debts and that his angry father wants him “to meditate and to better his ways”; the movie Lorens, more dramatically and “cinematically,” is sent to the country when he burps loudly and involuntarily in front of a superior officer.

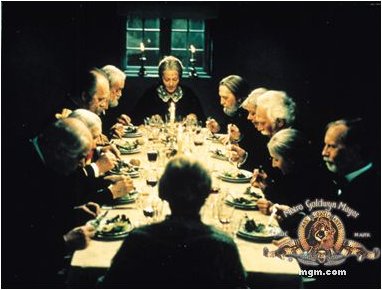

The most serious change made by Axel, one could argue, is conceptual and ideological: the movie has a 19th-century setting, but not a 19th-century sensibility. The extensive expansion of the story’s central incident — Babette, after winning 10,000 francs in a French lottery, decides to blow it all on an elaborate gourmet meal for Martina and Philippa’s congregation, to celebrate the 100th birthday of their late minister father — certainly transforms the meaning of the original by placing the emphasis on the meal’s consumption rather than its production. (Nearly all of the film’s corniest ploys — like a parishioner who periodically declares “Hallelujah!” to express his sensual pleasure in the meal — stem from this change.)

Indeed, it’s far from accidental that tie-ins with expensive gourmet restaurants in various American cities are central to the promotion of Babette’s Feast, which effectively converts the movie into an ad for another consumer product — a come-on for upwardly mobile gourmets rather than a work that is satisfying and complete in its own right. The comedy of the sensually inhibited religious community enjoying the meal almost against their own wills seems to score in an American context, much as The Decline of the American Empire did, precisely because the characters aren’t speaking English, which limits the extent to which American audiences are able to identify directly with the characters’ hang-ups. The language barrier that makes spectators in this country intolerant of most subtitled movies seems less operative if their relation to the action is more voyeuristic and pornographic, in which case the foreign language helps to distance them from the characters.

My major biases against Babette’s Feast, which are related to the above, can be summed up by two names: Orson Welles and Carl Dreyer. It isn’t Axel’s fault, of course, that he and Sydney Pollack should have so much more commercial luck with Dinesen than Welles ever did, but the differences are nonetheless instructive. And a consideration of the fact that this Danish film stars Birgitte Federspiel (as Martina), who played the female lead in Dreyer’s Ordet 30-odd years ago, leads one to some related reflections.

Welles worshiped Dinesen to such a degree that her importance to him was second only to Shakespeare’s. Between the late 1940s and his death, he had plans to film at least a half dozen of her tales — including “The Old Chevalier,” “The Deluge at Norderney,” “The Dreamers,” “Echoes,” and “The Immortal Story.” The last of these was the only Dinesen adaptation Welles managed to complete on film, in 1966, and even here, the budget was so minuscule — and the film visibly suffers from it — that Welles had to kick in an additional $45,000 of his own. “The Dreamers” and “Echoes,” Dinesen’s two stories about Pellegrina Leoni, formed the basis of the most treasured of all his late projects, called successively Da Capo and The Dreamers and developed between 1978 and 1985 — a script he revised at least eight times.

I would happily trade all of Babette’s Feast, and Out of Africa to boot, for the four-minute scene from The Dreamers that Welles filmed in his backyard a few years ago, at his own expense, with Oja Kodar as Pellegrina and himself as Marcus. It describes the crucial moment when Pellegrina, an opera singer who has lost her ability to sing, prepares to leave her villa in Milan to lead a series of different lives under new identities. For all its simplicity, it has all the qualities Babette’s Feast conspicuously lacks: grand passion, mystery, the voluptuous flow of Dinesen’s language (turned into a melodious duet for Welles and Kodar), story-telling magic, and a liquid romantic style. While it clearly isn’t Axel’s responsibility that Welles couldn’t make films, it is relevant to point out that the culture that supports Babette’s Feast and the culture that refused to support Welles’s Dinesen projects are one and the same.

Like “The Dreamers” and “Echoes,” though on a much more modest scale, “Babette’s Feast” can be read as an artist’s metaphor for her own practice — specifically, the disinterested exercise of her own skill. Axel doesn’t eliminate this meaning, but he manages to submerge or blur many of its implications. One of his pointed omissions in the film is Dinesen’s suggestion that Babette was a Petroleuse — a thrower of Molotov cocktails — in Paris during the Commune struggles. Thus the fact that Lorens, now an elderly officer, is the most appreciative and knowledgeable of Babette’s dinner guests carries a complex irony that Axel chooses to do without.

Dreyer is a filmmaker who had even more difficulty in financing his projects than Welles did; if we compare his 1955 Ordet — a film with roughly the same setting (a rural religious community in Jutland where religious ceremonies are conducted in homes rather than churches) — to Babette’s Feast, we again get a striking look at the latter’s shortcomings. Although Dreyer was neither rural nor religious himself, his grasp of the local community is so detailed and convincing that one could never guess it; Axel, by contrast, sketches it fairly cursorily and patronizingly, and not very persuasively. The materiality, sensuality, and carnality of Dreyer’s world is equally remote from Axel’s, whose sense of eroticism is pretty tame by comparison.

For all their radical differences, Welles and Dreyer were both dedicated to brutal re-creations of the world in all its physicality and density. Axel, by contrast, is interested in getting a few giggles out of a minor story by a great writer — a great writer who, ironically and tragically, consuming only oysters and champagne at the end of her life (she died in 1963), died of malnutrition. This is obviously not the Isak Dinesen that the public wants to hear about; and to Gabriel Axel’s everlasting profit, it is not the Isak Dinesen that he offers. Indeed, the incandescent style suggested by Eudora Welty’s description of Dinesen’s method, quoted at the beginning of this review, couldn’t be further removed from Axel’s method. About him one might say: “Of a story, an essence, and an elixir he made a consumer product.”