From Film Quarterly, March 2007, vol. 60, no. 3; reprinted in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. Obviously some of this is out of date by now. — J.R.

There’s a part of me that understands perfectly why a

minimalist like Jim Jarmusch and a 19th century figure like

Raul Ruiz won’t have anything to do with email. “You can’t

smell email,” Ruiz once said to me, to explain part of the

reason for his distaste. But I find it tougher to feel

nostalgic about film criticism before the Internet, because

even though you could smell it, the choices of what you

could lay your hands on outside a few well-stocked

university libraries were fairly limited. Similarly, the

choices of what films you could see outside a few cities

like New York and Paris before DVDs was pretty narrow, and

possibly even more haphazard than what you could read about

them.

These two developments shouldn’t be considered in

isolation from one another. The growth of film writing on

the web —- by which I mean stand-alone sites, print-magazine

sites, chatgroups, and blogs —- has proceeded in tandem with

other communal links involving film culture that to my mind

are far more important than the decline in the theatrical

distribution of art films and independent films, so I’ll be

periodically discussing those links here.

When I started out as a cinephile in New York in the

early 60s, the English-language magazines that counted the

most were the ones that went furthest in gathering together

diverse constituencies: Sight and Sound, Film Culture, and

Film Quarterly. Even the more local and partisan New York

Film Bulletin was translating texts from Cahiers du Cinéma.

Of course the film world was much smaller then, and some of

the nostalgia for that era undoubtedly focuses on the

coziness. By the time film writing on the web started, film

culture had spread and splintered into academia and

journalism, which often lamentably functioned as mutually

indifferent or sometimes even mutually hostile

institutions. So the theoretical golden age, I assume, took

place before all the institutionalizing.

Significantly, the most enterprising early efforts to

disseminate film writing on the web were neither American

nor English but Australian —- most notably the academic and

peer-reviewed Screening the Past, founded by classical and

fine arts scholar Ina Bernard in Melbourne in 1997, and the

more journalistic Senses of Cinema, founded by filmmaker

Bill Mousoulis in the same city in 1999. Both publications

are still going strong — having published 19 and 40 issues

respectively by late 2006, and continuing to keep all their

previous issues online, although Senses underwent several

changes after the departure circa 2002 of Mousoulis and

another editor, critic Adrian Martin, the latter of whom

went on to cofound the no less ambitious Rouge in 2003.

It’s easy to hypothesize that this Australian concentration

came from both a highly developed and interactive local

film community and a desire both to be recognized by and to

communicate with the wider world of cinephilia.

Three other extremely useful film sites that have by

now become regarded as staples include the English and

academic www.film-philosophy.com, the American and

basically journalistic http://daily.greencine.com/, and the

international www.mastersofcinema.com (which functions

mainly though not exclusively as a guide to what’s coming

out on DVD) — all especially valuable, as is Senses, as

conduits to other sites. Then there are the sites

maintained by film magazines (e.g., Sight and Sound, Film

Comment, Cineaste, Cinema Scope), which offer samples

rather than exhaustive duplications of their latest issues,

and those sites that have replaced former magazines on

paper, such as Bright Lights.

My acquaintance with blogs and chatgroups has been

more limited, but a few of each might be mentioned here.

Among the more notable critics’ blogs are ones devoted to

Serge Daney in English (http://sergedaney.blogspot.com) and

to Raymond Durgnat (currently in hiatus, though expected to

return [2016: it’s now back]), ones maintained by Fred Camper, Steve Erickson, Chris Fujiwara, and Dave Kehr, and Saul Symonds’ www.lightsleepcinemamag.com, which also originated in Australia, and prints or reprints a few texts by other critics not readily available elsewhere. And the main

chatgroups I’m familiar with are the auteurist “a film by,”

“film and politics” (which started out as a splinter group

deriving from the former, and is also on Yahoo), and a few

separate chatgroups located on the elaborate site

www.wellesnet.com (“the Orson Welles web resource”). The

latter calls to mind a slew of other director-based sites,

including especially impressive ones devoted to Robert

Bresson, Carl Dreyer, Jonas Mekas, and Jacques Tati.

***

How wide are the readerships of such resources? Klaus

Eder, who for many years has been the general secretary of

FIPRESCI, the international film critics organization,

recently told me that Undercurrent — an online, Englishlanguage

magazine established on their website in 2006, edited by Chris Fujiwara, that has so far published only three issues —- had about 100,000 readers per month. Considering how specialized the magazine’s turf is — encompassing such topics as the late film critic Barthélemy Amengual, Alexander Dovzhenko, the acting in Don Siegel’s Madigan, Austrian cinema, sound designer Leslie Schatz,

assorted short films, and recent features about Cameron

Crowe, Philippe Garrel, Danièle Huillet, Terrence Malick,

Park Chan-wook, and Tsai Ming-liang — and considering that

100,000 readers seems to comprise more than those of all

film magazines on paper combined, this was a startling

piece of information, and one that initially beggared

belief. It was also hard to square this figure with one

given to me by Gary Tooze regarding a recent piece of mine

called “Ten Overlooked Fantasy Films on DVD (and Two That

Should Be!)” on his much more commercial and consumer oriented web site, DVD Beaver. (In that case, he estimated

about 10,000 hits during the first week the article was

posted.) But once Klaus added that the average length of time

spent by each reader of Undercurrent was roughly two

minutes, I started to realize that my shock was premature,

and that my superimposition of two incompatible grids —- one

devoted to subscribers and readers of paper magazines such

as Cahiers du Cinéma, Film Quarterly, and Sight and Sound,

the other devoted to web surfers —- could only lead to

muddled conclusions. And I’m not sure that the comparison

with DVD Beaver is very meaningful without the average

length of time of each hit in that case, which I don’t know.

I also recently learned from David Bordwell that his

web site at www.davidbordwell.net “receives between 250-450

unique visitors each day, with an average of 2-3 pageloads per visitor.

Most visitors on any day are first-time visitors, with about 60-100

coming back from a previous day. Heaviest usage is from the US and

Europe, which you’d expect.” I don’t think we can meaningfully

compare these figures with the sales of Bordwell’s books

(which I didn’t ask him about), and I’m not even sure how

meaningfully we can compare Bordwell’s site with

Undercurrent, given the range of things that web-surfers

are looking for. Bordwell largely uses his site to update

and expand many of his writings on paper, and this already

points to functions that are qualitatively different from

those of published works.(1)

Extrapolating from all this, I started to realize that

current claims that film criticism is becoming extinct, and

counter-claims that it’s entering a new golden age, are

equally misguided if they assume that film criticism as an

institution functions the same way on paper and in

cyberspace, as two versions of the same thing rather than

as separate enterprises. Related debates about the

distribution of foreign films in the English-speaking world

(drastically shrinking in theaters, drastically expanding

in the production and distribution of DVDs), or the

sophistication of young filmgoers regarding film history

(growing if you follow some chatgroups, declining if you

follow certain others), or the number of films that get

made (even more difficult to determine if videos and films

are treated interchangeably) seem equally incoherent due to

the disparity of reference points, creating a Tower of

Babel in a good many discussions. It’s a central aspect of

our alienated relation to language that when someone says,

“I just saw a film,” we don’t know whether this person saw

something on a large screen with hundreds of other people

or alone on a laptop —- or whether what he or she saw was on

film, video, or DVD, regardless of where and how it was

seen.

In short, we’re living in a transitional period where

enormous paradigmatic shifts should be engendering new

concepts, new terms, and new kinds of analysis, evaluation,

and measurement, not to mention new kinds of political and

social formations, as well as new forms of etiquette. But

in most cases they aren’t doing any of those things. We’re

stuck with vocabularies and patterns of thinking that are

still tied to the ways we were watching movies half a

century ago.

If we consider briefly just the question of email and

chatgroup etiquette, we already encounter a daunting array

of new kinds of behavior. If sending an email to someone

can sometimes partake of the kind of intimacy associated

with whispering, there are also arguably new forms of

interpersonal brutality that crop up periodically in

chatgroups, obliging some leaders of such groups to impose

certain standards of civility between members. Even

definitions of what constitutes a stranger or evaluations

of the importance of typos has undergone a certain amount

of transformation within the new context of chatgroups, and

there are few of us who aren’t still finding our bearings

within such contexts.

***

In order to grasp some of the new tricks that some of

the old dogs are failing to learn, it helps if we start

redefining what we mean by community in relation to

geography, which is central to all these paradigmatic

shifts. It becomes relevant, for example, that Fujiwara

edits Undercurrent from Tokyo as well as from Boston, and

that the editor of Film Quarterly, published by the

University of California Press, works out of London —- and

perhaps even that this sentence is initially being written

on a plane between Chicago and Vancouver —- especially if we

persist in regarding the discourse of both magazines as a

discourse being aimed at a specific geographically-based

constituency seen in relation to a particular nation-state,

town or city, university or other institution. Speaking as

someone who currently feels that he lives on the Internet

more than he lives in Chicago, I consider this distinction

vital to the ways that I function as a writer. Maybe it’s

also relevant that Rouge, the most ambitious of the

international online film magazines (translating some of

its texts into English from Chinese, French, German,

Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, and Spanish sources),

originates from Australia —- or at least from three

Australian editors, who may at any given time be in France,

Greece, or elsewhere while doing part of their editorial

work. But if it is relevant, this is largely because

Australia is itself multicultural, also yielding a

multicultural, state-run TV channel, SBS, that similarly

has few counterparts.

It’s my own conviction that the nation-state itself is

fast becoming an outdated and dysfunctional concept, apart

from the special interests of politicians and corporations

and their own highly functional designation of countries as

markets. It seems bewildering that while most of the world

appears to detest George W. Bush as much as I do, this fact

has been deemed totally irrelevant to political strategy

and activity within the Democratic Party, so that the U.S.

currently appears to be more isolated from the rest of the

world than it was during the cold war — in spite of the

unprecedented possibilities of communication and

interactivity made possible by the Internet. And if we

scale down this striking paradox to the more modest

dimensions of film culture, the same anomalies are

apparent. The choices of ordinary filmgoers are said to be

steadily shrinking at the same time that most of the riches

of world cinema are becoming internationally available for

the first time on DVD.

Part of our problem in assessing our new conditions is

a bad habit of often assuming by reflex that they’re either

bad or good —- which is about as futile as arriving at such a

simplistic conclusion about globalization. Let me try to

illustrate this with a couple of extended personal

anecdotes. Shortly after September 11, 2001 attacks, I was

invited by the Chicago Reader’s editor to write something

reflecting on its aftermath. After she decided not to run

my article, I received a similar invitation from Senses of

Cinema, and emailed them the same piece, somewhat rewritten.

I wrote about my fear of what I described as American

as well as Middle Eastern terrorists —- by which I meant

Americans who suddenly started thinking about the vanished

World Trade Center as if it were their own private property

and the attacks of September 11 as if they were simply and

unambiguously an “attack on America,” thereby allowing the

Middle Eastern terrorists and their assumed positions to

set all the terms of the discussion and automatically

dismissing the non-Americans from over 80 countries who

were destroyed in the attacks as irrelevant. I was

especially upset by a poster with an American flag over the

words “September 11, 2001/We Will Not Forget,” placed on

the front door of the building where I live in Chicago by

an upstairs neighbor, who didn’t bother to consult anyone

else in the nine-unit building about it. Feeling that flags

were already being used to intimidate, to stop

conversations rather than start them, I objected at our

next condo meeting that “we will not forget” in this

context meant that we will forget all the non-Americans

killed —- at which point my neighbor left the room and

refused to discuss the matter further, with the result that

his poster remained up for many weeks afterwards. I

concluded that I was tempted to attribute part of this

terrible climate to a certain “narcissism about mourning”

that a visiting German filmmaker had recently mentioned to

me about some of her New York friends and acquaintances.

Less than an hour after the issue of Senses of Cinema

containing my article appeared online, I received an

abusive email from a New York film critic whom I knew only

slightly and who wrote me, in a fit of rage, that I had no

moral right to accuse people like him of being narcissistic

about mourning when he could still smell the ashes of burnt

flesh from his apartment. So three extremely disparate and

irreconcilable definitions of community were affecting me

all at once: a feeling of repression, censorship, and

bullying in the building where I live; an ability to

express this feeling freely and openly to like-minded

individuals on a web site located on the other side of the

planet; and an almost traumatic sensation of being

assaulted by an acquaintance 800 miles away for expressing

the same feeling. The first and last of these experiences

were nightmarish and dystopian, the second was utopian, and

the second two were possible only because of the Internet —

because I can’t imagine that the New York acquaintance

would ever have phoned me with the same message. And only

the first was geographically matched with where I happened

to be.

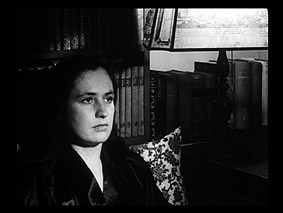

My second anecdote relates to the recent death of

Danièle Huillet, the filmmaking partner of Jean-Marie

Straub, and how this was both discovered and dealt with by

many people via “a film by”. Shortly after I learned about

this shocking and upsetting occurrence, when a friend in

New York, critic Kent Jones, phoned me, I posted what

little information I had in this chatgroup, and for roughly

the first 24 hours there was little if any response. But

when responses then started to come, they were detailed and

far-ranging, and came from such diverse quarters as Los

Angeles, Paris, the American Midwest, and Melbourne. They

included photographs of Huillet as a little girl growing up

on a farm (posted at http://kinoslang.blogspot.com, and furnished by Bernard Eisenschitz), which I had never even known existed, information about the first digital video of Straub-Huillet (which later proved to be obtainable online), links to an article in Libération and many older English- language texts —- and a detailed (and somewhat contentious) discussion about an obituary written by Dave Kehr for the New York Times, an obituary that conceivably might not have been written if the news about Huillet’s death hadn’t been posted in “a film by”.

More generally, the kind of discourse and behavior one

encounters in “a film by” seems to run the gamut from news

and critical analysis to childish and protracted exchanges

of insults — a mix that is by no means restricted to

chatgroups dealing with film, and which also can be

characterized as split between occasional and habitual (or

even compulsive) contributors — those who periodically visit

and those who appear to do very little apart from exchange

comments. Significantly, this particular group was

initially formed by critics Fred Camper and Peter Tonguette

to counter the impolite behavior in other film chatgroups,

and it continues to be monitored for that reason, but this

hasn’t prevented the discussions from periodically

descending into invective that overwhelms other forms of

communication. It would be interesting to hear from

psychologists and/or psychoanalysts about the psychic

reservoirs and “family plots” that appear to be tapped into

by these exchanges, leading to forms of behavior that seem

to be specific to the Internet and periodically undermine

some of the more progressive and utopian possibilities.

Thanks to the site of www.cinema-scope.com, where I

write a regular column called “Global Discoveries on DVD”

that usually appears online, I received one of the most

exciting glimpses of the utopian possibilities inherent in

film writing on the web. For some time, I have been

fantasizing that ciné-clubs, a major spur to French

cinephilia over most of the past century, could be making a

comeback, this time in global terms, thanks to DVDs. These

ciné-clubs could be situated almost anywhere, in houses and

configuration might be touring “retrospectives” on DVD in

which the DVDs could be sold at the screenings (perhaps

along with relevant books and/or pamphlets), in much the

same way that CDs are now often sold by music groups in

clubs between their sets. And if enough circuits for these

retrospectives could become established in this fashion,

this could ultimately finance the production of these

packages. In some ways this dream has already been realized

in the U.S. by www.moveon.org and the way it has arranged

private showings of such Robert Greenwald documentaries as

Uncovered, Out-Foxed, Wal-Mart, and Iraq for Sale, but it

doesn’t appear to have caught on with other kinds of films.

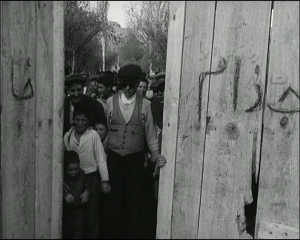

While attending the Mar del Plata film festival last spring, I met a schoolteacher based in Cordoba who had

established a few ciné-clubs in separate small towns that

he visited on a regular basis, and the films he showed

included some of the more specialized and esoteric films I

had written about, including Forough Farrokzhad’s The House

is Black (1962) and Kira Muratova’s Chekhov’s Motifs (2002).

He told me the combined audiences of such screenings for

each film was somewhere between 700 and 800 people.

Considering how unlikely it would be to fill single

auditoriums of that size in most major cities of the world

for such films, I realized that the shifting paradigms of

today might also transform what we normally regard as a

minority taste. Once the paradigm of a single geographical

base changes, all sorts of things can be transformed. Maybe

Muratova’s craziest feature is too difficult for most New

Yorkers and Parisians, but once it can be acquired globally

on DVD with the right subtitles, anything becomes possible

—- including a sizable group of viewers in Cordoba.

1. I was chagrined to discover that an essay of mine on

Eyes Wide Shut reprinted in American Movie Critics by

the Library of America, a publisher celebrated for

its “definitive” editions, introduced a typo in the

opening paragraph that reversed the meaning of the

sentence, changing “argue” to “agree” —- a typo that

hadn’t occurred in any of the article’s three other

appearances on paper. Ironically, if such a typo had

occurred in the Chicago Reader, where the article

first appeared, it could have been corrected a day

later in the Reader’s online edition, whereas the

Library of America’s typo, barring a second edition,

is permanent. [2009 Postscript: although a correction

sent to the Library of America went unacknowledged,

the subsequent paperback did correct the error.]

But this doesn’t necessarily make the Reader’s

online system superior in all respects. For the past

several years, due to space restrictions regarding

the Reader’s paper edition, all its capsule film

reviews that run past a particular length now have to

be permanently shortened for both the paper and its

online editions. Thus the older issues on paper

preserve longer capsules that are no longer available

anywhere else, while the capsules available online

can theoretically be altered on a week to week basis

and thus have none of the same archival status and

value.

— Film Quarterly, March 2007, vol. 60, no. 3