Note: Unlike some of my colleagues, when I say “available,” I mean in this case available on region-2 discs that can be played on multiregional players, which are easy and inexpensive to come by.

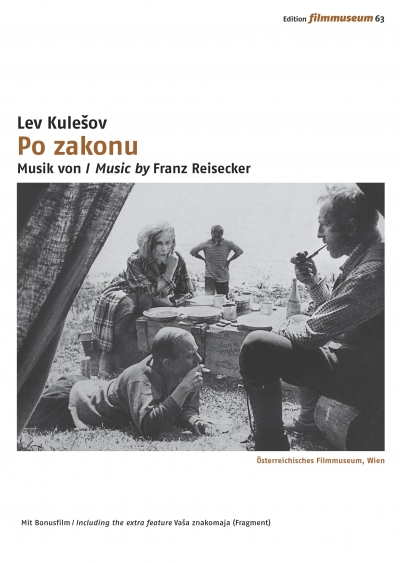

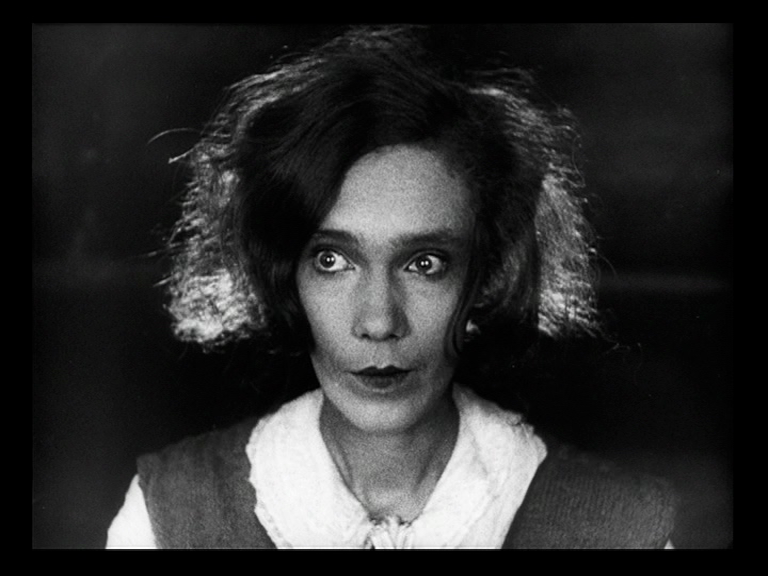

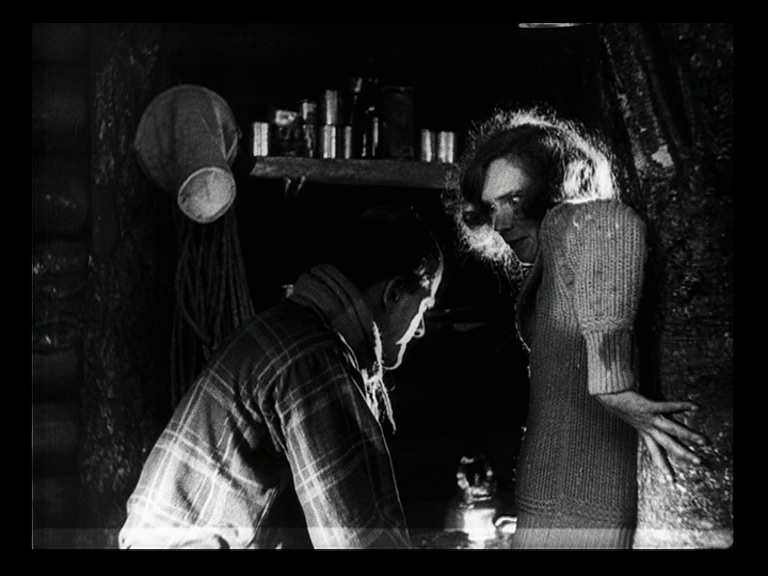

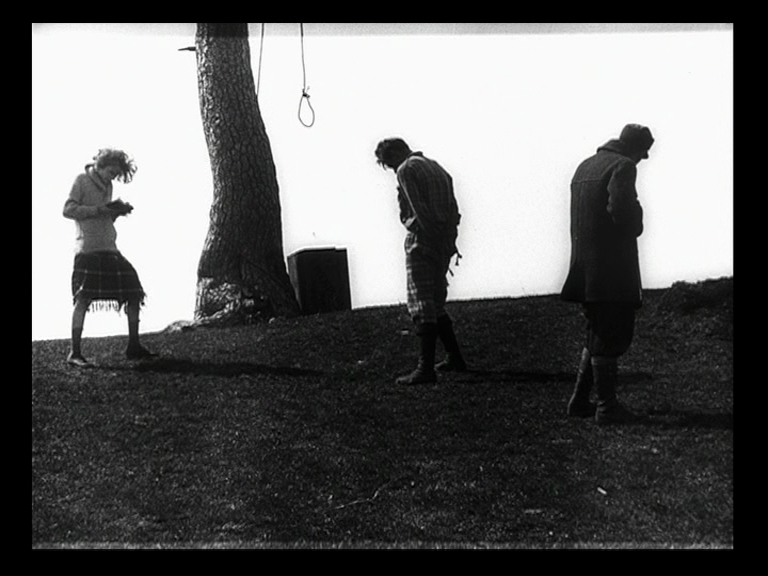

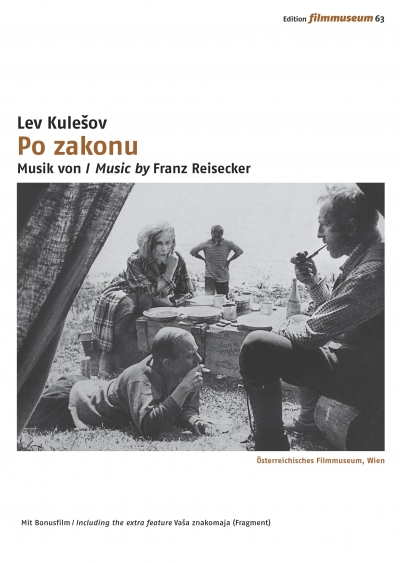

By the Law aka Dura Lex (Po kanonu), directed by Lev Kuleshov 1926 from a script by Viktor Shklovsky that’s adapted from a Jack London’s story (“The Unexpected”), packaged with an 18-minute fragment of Kulshov’s 1927 Your Acquaintance and a bilingual, illustrated 16-page booklet, is available from www.edition-filmmuseum.com for a little under 20 Euros via PayPal.

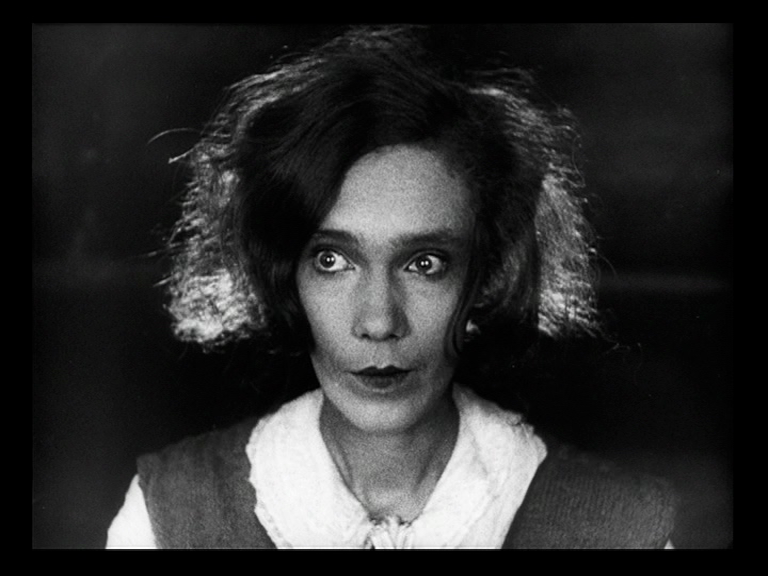

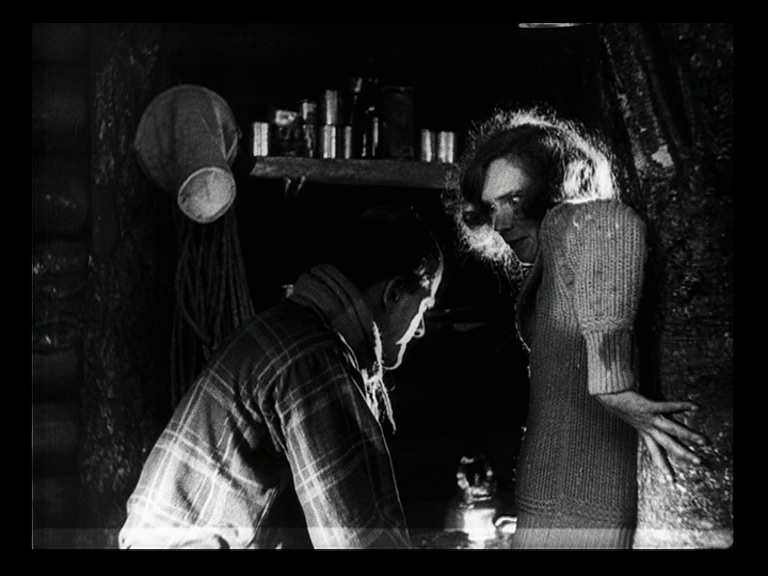

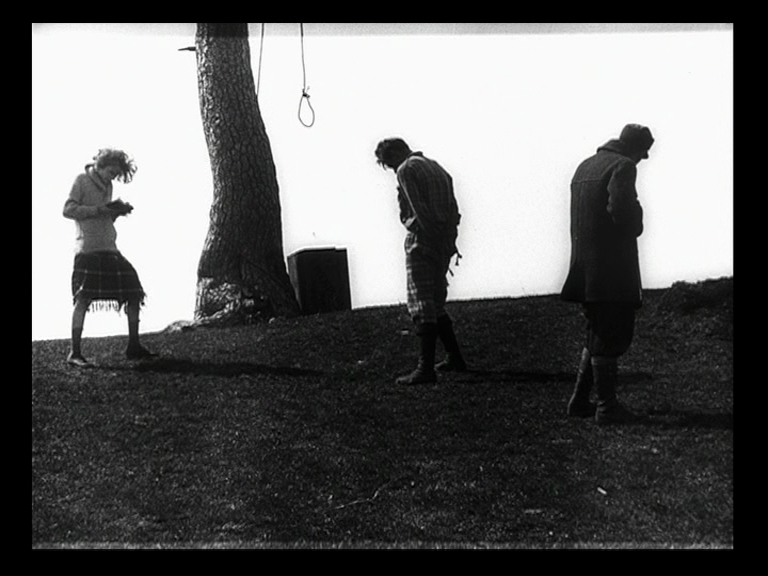

The other two DVDs are of Alexander Dozhenko’s first two masterpieces, Zvenigora (1928), seen above, and Arsenal (1929), seen below. (In both cases, as in By the Law, these frame-grabs come from my own reviewer copies, and were selected almost at random.) The two Dovzhenkos are currently available from an English company, Mr. Bongo that previously released an excellent version of Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930), the final feature in what is sometimes called his silent war trilogy, which my west coast colleague Doug Cummings was kind enough to alert me to. From February 14, when Zvenigora and Arsenal are being released, English Amazon is offering each for just under 8 pounds (a little under $13), an incredible bargain. Read more

From The Soho News, July 18, 1980. Also reprinted in my first collection, Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995). — J.R.

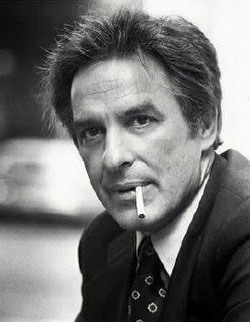

John Cassavetes, Filmmaker and Actor Museum of Modern Art, 20 June — 11 July

Nineteen years ago, when I was a high school senior making one of those boring, difficult adolescent transitions — from being a social outcast in my hometown in the Deep South to being a social outcast as a southerner at a New England prep school — I had the good fortune to discover John Cassavetes’s SHADOWS at the New Embassy at Broadway and 46th. It was near the beginning of my spring vacation, which meant that I could return to this movie again and again, during the same week or so when I was getting my first looks at BREATHLESS, THE RULES OF THE GAME, ROOM AT THE TOP, SPARTACUS, THE MISFITS, and TAKE A GIANT STEP.

Art in our time, Harold Rosenberg once wrote, appeals either to other artists or “to introverted adolescents, to people in crises of metamorphosis, a small-town girl who has met an intellectual, a husband forced to give up drinking, a business man who feels spiritually falsified, all these being, like the audience of artists, more attentive to themselves than to the work.” Read more

Written in 2010 for the Cinema Guild’s DVD release of Shirin. — J.R.

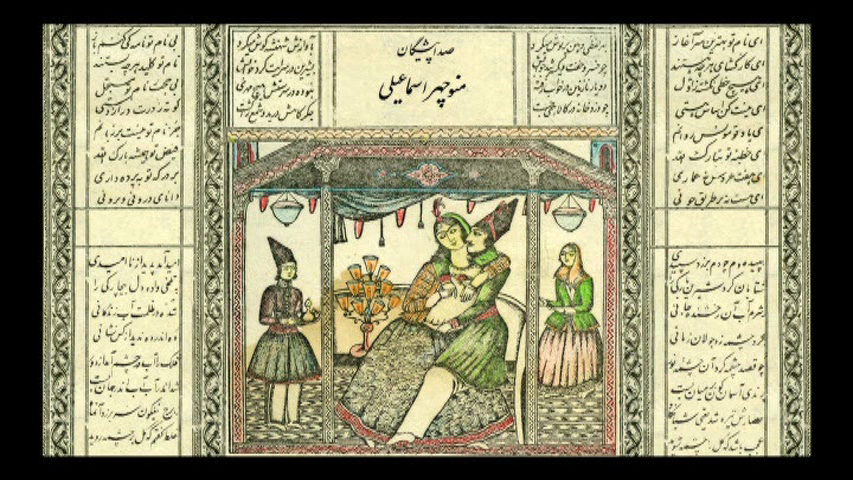

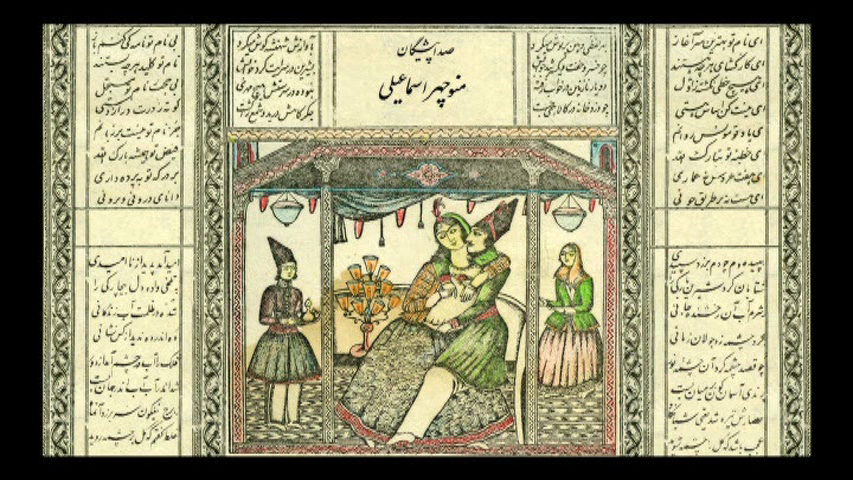

It doesn’t do justice to Shirin to call it the most conceptual of Abbas Kiarostami’s films. But it probably wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call it the most paradoxical. Not the least of its paradoxes is the way that it simultaneously confronts and defies the specter of commercial cinema, qualifying at once as his most traditional feature and his most experimental. By focusing almost exclusively on the fiction of women watching a commercial feature that we can hear but never see — a feature that in fact doesn’t exist, apart from its manufactured soundtrack — one might even say that Kiarostami, an experimental, non-commercial filmmaker par excellence, is perversely granting the wish of fans and friends who have been urging him for years to make a more “accessible” film with a coherent plot, a conventional music score, and well-known actors.

What’s perverse about this is that the plot in question, while drawing from a traditional epic, a medieval romance widely known in Iran, belongs to an unseen and imaginary film whose on-screen spectators are precisely those well-known actors. (Both men and women comprise this imaginary audience of 110 individuals, although the only viewers featured in close-ups are women.) Read more