Adapted and condensed from “Comparaisons à Cannes,” translated by Jean-Luc Mengus, Trafic no. 19, été 1996. -– J.R.

In his introduction to Understanding Media, Marshall McLuhan

records the consternation of one of his editors that “seventy-five

per cent of your material is new. A successful book cannot venture

to be more than ten per cent new.” From the vantage point of this year’s

Cannes Festival, a compulsion to contextualize everything new in

relation to something familiar reveals a comparable problem. Indeed, the

kind of movie pitch parodied at the beginning of Altman’s The Player,

in which every project becomes some version of one or two previous

hits — “The Graduate, Part 2,” “The Manchurian Candidate meets

Ghost” — has by now become a kind of journalistic shorthand for the

critic eager to make the film fully accessible once it’s released. This

necessity of establishing old references in relation to new ideas is above

all an indication of how thoroughly the priorities of the film business

have infiltrated film criticism.

As useful as this practice is, it often functions as a kind of nervous

tic. For the writer or speaker too lazy to perform the less alluring task

of description, it poses a constant temptation — a means of short-

circuiting the critical process through a kind of magic or alchemy that

suddenly makes the invisible visible. Read more

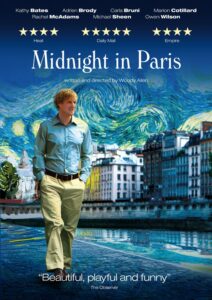

It seems that class anxiety has become Woody Allen’s key and obsessive theme ever since his movies started to become “serious”, and it’s usually around in some form even in the purer comedies. Indeed, almost all of the cultural concerns of his work wind up having something to do with class issues — almost as if Allen really believed the crazy American myth that espresso and wealth are inextricably interconnected. The main fantasy about expatriate American bohemians in Midnight in Paris isn’t really about art; it’s about Hemingway or somebody like that stepping into a cab and not worrying about having to pay the driver (which F. Scott Fitzgerald or T.S. Eliot can always take care of), and if Gertrude Stein likes your novel, the bottom line is social acceptance and approval, not artistic license or accomplishment.

From this point of view, Blue Jasmine represents Allen’s coming-out film, by virtue of placing his class anxieties front and center, not through embarking on any themes that are significantly new for him. The vague use of A Streetcar Named Desire (movie and play) as a loose model, with Cate Blanchett serving as a sort of Yankee Blanche DuBois, parallels the vague uses of A Place in the Sun and An American Tragedy in Match Point. Read more

From the June 4, 1999 Chicago Reader. A lot of the material here subsequently turned up in my book Movie Wars. — J.R.

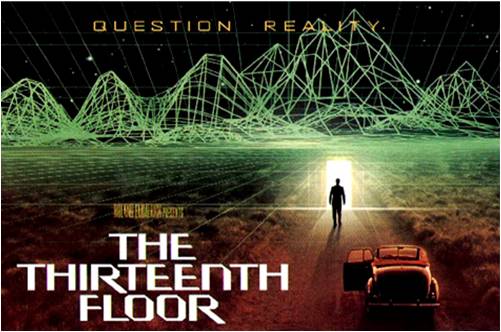

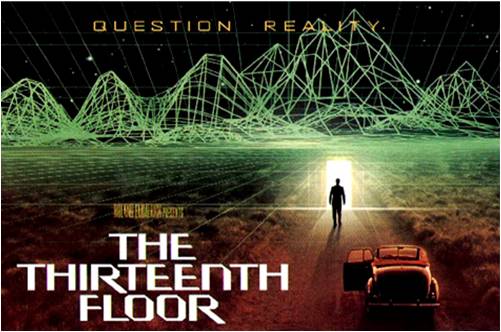

The Thirteenth Floor

Rating * Has redeeming facet

Directed by Josef Rusnak

Written by Rusnak and Ravel Centeno-Rodriguez

With Armin Mueller-Stahl, Craig Bierko, Gretchen Mol, Vincent D’Onofrio, Dennis Haysbert, and Steven Schub.

“I think, therefore I am,” reads the opening epigraph of The Thirteenth Floor, followed by the quotation’s source, “Descartes (1596-1650).” It’s an especially pompous beginning for a movie whose characters barely think, much less exist, but not too surprising given the metaphysical claims and pronouncements that usually inform virtual-reality thrillers.

This is the fourth such thriller I’ve seen in as many weeks, and if any thought at all can be deemed the source of these pictures cropping up one after the other — with the exception of David Cronenberg’s eXistenZ, a film with more than generic commercial kicks on its mind — it might be an especially low estimation of what an audience is looking for at the movies. The assumed desire might be expressed in infantile and emotional terms: “I don’t like the world, take it away.” In other words, for filmmakers stumped by the puzzle of how to address an audience assumed to be interested only in escaping without reminding them of what they’re supposed to be escaping from, virtual-reality thrillers seem made to order. Read more

One wouldn’t expect Albert Brooks’s first novel (Twenty Thirty: The Real Story of What Happens to America) and Woody Allen’s latest movie (Midnight in Paris) to have much in common, especially after one considers that the former is set 19 years in the future whereas the latter is set at least partially between eight and nine decades in the past. But the main thing they do have in common is in fact very contemporary — a preoccupation with money, which Brook’s novel is especially up front about. Both are also ultimately more interested in wisdom than in laughs (or, for that matter, in literature, at least for its own sake); Brooks’s own form of humor, which he seems to find impossible to suppress, is mainly a creative form of sarcasm, which he plants in many of his characters (all of them male, as it happens); more generally, much of his novel’s tone is fairly dour and cautionary. And the principal thing it’s dour and cautionary about is a very contemporary preoccupation with not having enough money. Read more