From Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema, Volume 1, No. 1, 2012 (a Spanish academic online journal, available at http://www.ocec.eu/cinemacomparative/pdf/ccc01.pdf). I’m reposting this after fixing a broken link. The Introduction to this long out-of-print book can be found here.– J.R.

“Rivette in Context” had two separate incarnations, occurring a year and a half apart. The first consisted of 28 programs presented at London’s National Film Theatre in August 1977, to accompany the publication of Rivette: Texts and Interviews — a 101-page book I had edited for the British Film Institute while still working on the staffs of two of its magazines, Monthly Film Bulletin and Sight and Sound, in 1976.

This book included a polemical Introduction by me and translations — most of them by my London flat mate, Tom Milne — of two lengthy interviews with Rivette (one in 1968 that was centered on L’amour fou, the other in 1973 that was centered on the two separate versions of Out 1), three key critical texts by him (“Letter on Rossellini,” 1955; “The Hand” [on Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt], 1957, and “Montage” [with Jean Narboni and Sylvie Pierre], 1969), and a brief, undated proposal of his from the mid-1970s (“For the Shooting of Les Filles du Feu” — the latter was the working title for a projected series of four features, never completed, that was subsequently retitled Scènes de la Vie Parallèle). Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 2002). — J.R.

Around 1950, after seeing his own ideas rejected time and again, the great Soviet director Alexander Dovzhenko undertook this grotesque piece of kitsch, which was inspired by the defection of U.S. journalist Annabelle Bucard after she discovered that the U.S. embassy in Moscow, where she worked, was a nest of spies. Dovzhenko’s script went through countless drafts, and when Stalin terminated the project (for reasons that are still obscure), the director learned the news only when the electricity was abruptly shut off on the soundstage where he was working. The film was finally released in 1995, with commentary on the missing pieces and material about its arduous birth, and it’s morbidly fascinating as an example of Stalinist filmmaking (Dovzhenko’s style is nowhere in evidence). Considering the director’s stature, the most depressing aspects of this are that even the commentator isn’t sure whether it’s sincere and that ultimately it doesn’t matter much. In Russian with subtitles. 73 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

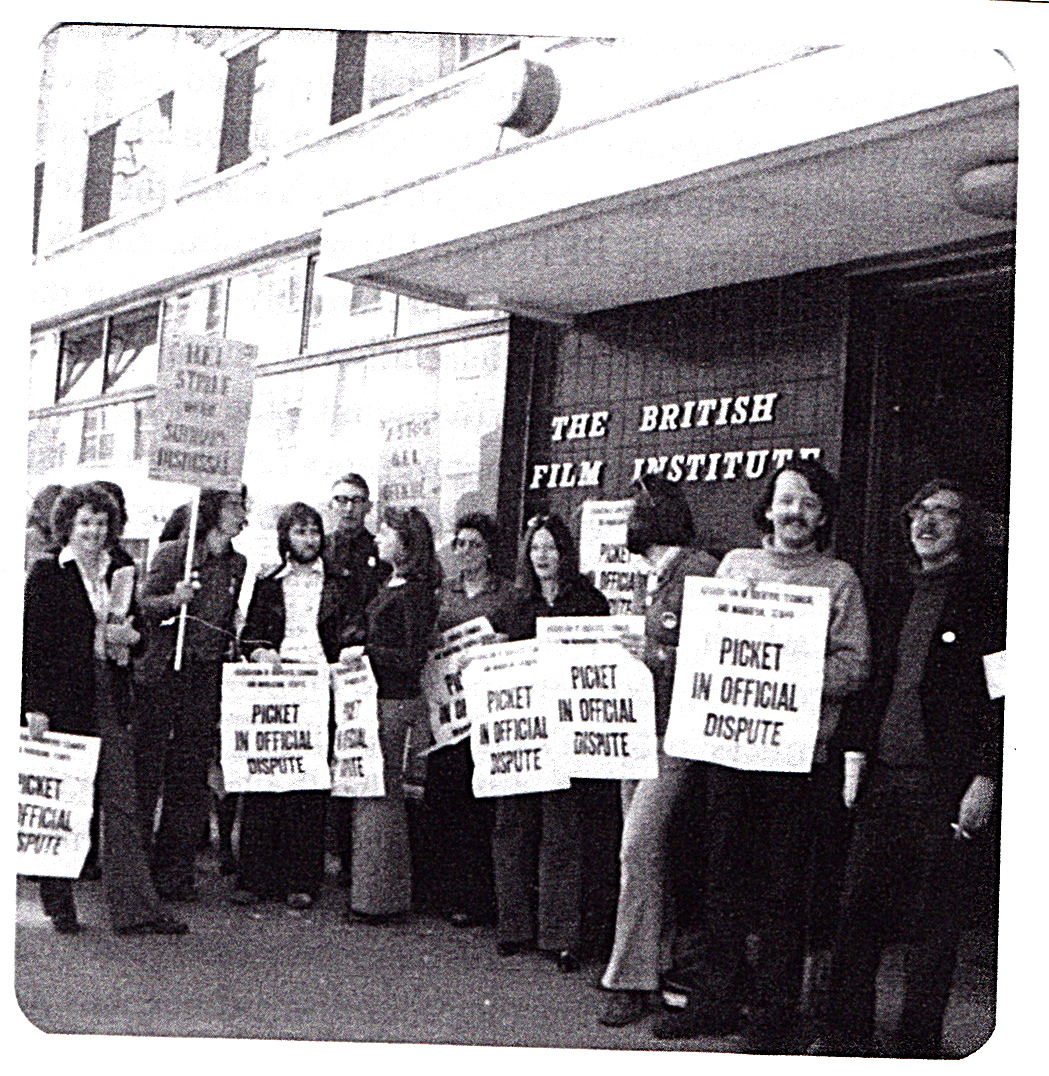

That’s me on the extreme right, next to my new boss at the time, Richard Combs. The address is 81 Dean Street, the main headquarters at the time of the British Film Institute. I’d started my new job there as assistant editor of Monthly Film Bulletin on August 5, working under Richard, and had joined the staff’s trades union, ASTMS, around the same time. But only a week or so later, after the National Film Archive’s acting curator, Kevin Gough-Yates, was summarily sacked, I attended my first union meeting, and seconded the motion that we go on strike to protest management’s refusal to follow proper procedures.

Our strike lasted a couple of weeks, and, as I recall, it was mainly successful. For me, it was an ideal way to get to know many of my fellow staffers at the BFI, and I also successfully collared Otto Preminger, emerging from an editing studio next door, where he was working on Rosebud, to sign our petition. (I had watched a morning’s shoot on Rosebud in Paris a month or so earlier and had been part of Preminger’s lunch party, so he remembered me.) According to Geoffrey Nowell-Smith in The British Film Institute, the government and film culture, 1933-2000, a recent book from Manchester University Press that he coedited and partially wrote (which is where this photo comes from), “Preminger sent a message from his suite at the Dorchester Hotel”. Read more