From the Chicago Reader (June 8, 1990). — J.R.

TOTAL RECALL

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Written by Ronald Shusett, Dan O’Bannon, Jon Povill, and Gary Goldman

With Arnold Schwarzenegger, Rachel Ticotin, Sharon Stone, Ronny Cox, Michael Ironside, Mel Johnson Jr., and Marshall Bell.

The most influential SF movies of the past two decades are still very much with us, not only as landmarks but as continuing influences on newer release. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) gave us a whole slew of standbys, from the use of familiar brand names in outer space to a sense of visual design that, as critic Annette Michelson once put it, dissolved the very notion of the “special effect” as it was previously understood. In 1977 Star Wars popularized the notion of SF adventure as continuous action; and Close Encounters of the Third Kind the same year brought a certain pop religiosity (or perhaps one should say pseudoreligiosity) back to the genre, a combination of De Mille and Disney that sanctified Spielberg lighting as a means of bestowing halos on deserving characters, creatures, or locations.

Alien (1979) revitalized the claustrophobic horror-film dynamics of The Thing (1951), internalizing the monstrous and echoing David Cronenberg’s feature of 1975, They Came From Within. Blade Runner (1982), probably the most visually handsome SF effort since 2001, had the merit of making the sordid, dystopian future — unlike the present in most Hollywood pictures — seem lived in, and gave us attractive androids, objects that helped reformulate the ideology of sexuality. The Terminator (1984) built upon both of these ideas; it established Arnold Schwarzenegger as an iconographic axiom in the heavy-metal android division, and it posited that a plausible happy ending could only be set in a postnuclear future. Finally, Robocop (1987), seeming equally indebted to Blade Runner and The Terminator, streamlined both into a vehicle for violent action spiced with cynical satire about the moral ugliness of the Reagan era.

The aptly named Total Recall somehow manages to incorporate certain aspects of all of the above-mentioned models without ever coming across as strictly derivative or imitative — a rather neat accomplishment in its own right. Strictly speaking, its ancestry stretches back even further to This Island Earth (1954) and Forbidden Planet (1956), probably the two best studio SF efforts of the 50s in terms of alien landscapes, fanciful technology, and extraterrestrial architecture. (The scenic imaginations of Total Recall‘s production designer William Sandell and “conceptual artist” Ron Cobb are much better than the norm although earlier and tackier 50s models such as George Pal’s When Worlds Collide also seem to be models in some spots.) And while the movie’s steady diet of violence tends to limit some of its narrative options and blunt its visceral edge, it succeeds pretty well in delivering a complicated plot with functional, no-nonsense story telling. (This is all the more impressive for a screenplay that, according to Kenneth Juran in the June Gentlemen’s Quarterly, went through 62 drafts and was 16 years in development.)

Consider just a few of the initial plot premises (they involve some early surprises, so proceed at your own risk):

Doug Quaid (Schwarzenegger), a construction worker with a devoted wife (Sharon Stone) on Earth in the year 2084, suffers from recurring nightmares set on Mars, where he appears in the company of a mysterious woman (Rachel Ticotin).

Mars, now colonized by Earth, is ruled by a capitalist dictator named Cohaagen (Ronny Cox), who controls the planet’s oxygen supply; the principal oppressed minority is made up of mutants, freaks born of parents exposed to deadly rays through “cheap domes.” Cohaagen’s forces and the Mars Liberation Front, which represents the mutants’ interests, are currently at war.

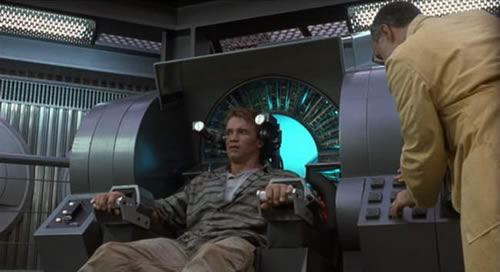

While riding the subway to work, Quaid sees an advertisement on TV for Rekall Inc., which sells not holidays but memories of holidays. The theory is that actual vacations are such a nuisance, ideal memories of same — decked out with imaginary identities — are infinitely preferable. Tormented by his dreams of Mars, Quaid signs up for a fantasy trip to Mars “as a secret agent.” But something goes wrong — Quaid freaks out and is sedated so that he can no longer even remember having gone to Rekall.

He then discovers that he’s under surveillance and that people, afraid that Rekall has triggered dangerous real memories, are trying to kill him. His wife proves to be a spy, and Quaid finds out that his entire identity and all his memories have been implanted.

Fortunately he encounters a stranger who knows what’s going on, helps him to escape, and gives him a satchel full of helpful technical gadgets. One of these is a video recording of Quaid himself in his former identity imparting basic facts for the benefit of his amnesiac self (“Get ready for a big surprise: you are not you — you’re me”), as well as some explicit instructions (“Get your ass to Mars”). It turns out that Quaid is really Hauser, a former agent for Cohaagen’s Mars Intelligence who’d switched sides and needs the help of his future self, Quaid, in order to defeat the dictator.

This should give you an idea of how jam-packed and complicated the plot is even at the beginning. And though the movie features almost continuous violent, bone-crunching action while dosing out its multifaceted exposition, director Paul Verhoeven shows remarkable grace and lucidity, keeping everything in perpetual motion without landing the viewer in total confusion. There’s just the right amount of alienated displacement to conjure up the paranoid mood of Philip K. Dick’s 1966 short story, “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale,” which served as the basis for the script, but still enough straight-ahead, slam-bang action to satisfy the violence freaks who couldn’t care less about plot or satire. (Verhoeven’s previous features The 4th Man and Robocop seem to indicate that good-natured malice and sadistic violence are his main calling cards, and these are distributed liberally to male and female characters alike.)

Don’t get me wrong: there’s something faintly ridiculous about any movie starring Arnold Schwarzenegger — just as 25 to 35 years ago, there was something faintly ridiculous about any movie starring Jayne Mansfield — and Total Recall, the best Schwarzenegger movie since The Terminator, is no exception. In the former movie he was a death-dealing machine who thought in computer printouts; this time he’s supposed to be a human amnesiac who eventually brings life to a dying planet. But in neither case does he function as a thinking character in any ordinary sense; what he really signifies is an expensive piece of heavy equipment: a set, a landscape, a vehicle. Happily, Schwarzenegger seems to be as aware of this as anyone else; and if much of this movie, kinetically speaking, is not much different from a very loud carnival ride — like being rammed in a bumper car from all sides — there’s still enough wit and intelligence to keep one from blanking out between the collisions.

Throughout the nonstop action the movie seems to be ironically commenting on itself. The overall craft and authority with which it’s executed give the impression that the movie actually seems to know what it’s doing. (“Get ready for the ride of your life,” promise the ads, and Schwarzenegger is merely the vehicle for this trip.) The whole premise of a company like Rekall can be read as a metaphor for moviegoing, and Quaid’s martian dreams, his prerecorded instructions to himself, and various gadgets in the story — like the wall-size TV screens in Quaid’s kitchen and a device that allows him to project his own video image into the air like a simulacrum — all suggest various other aspects of the moviegoing experience. (Even Cohaagen’s capitalist control of the air on Mars, and the sealed-off environment that this control entails, call to mind some of the dictatorial and claustrophobic conditions of air-conditioned film viewing.) Generally speaking, this means that Quaid’s uncertainty about who and where he is, which we at times share, resemble those of a slightly weirded-out film addict.

Consider the following speech from Piers Anthony’s novelization of Total Recall published by Avon — the spiel of McClane, the Rekall salesman, to the hero — which is rather close in both spirit and detail to the movie:

“Let me tantalize you, Doug. It’s like a movie, and you’re the star. Thrills, chills, double identities, chases! You’re a top operative, back under deep cover on your most important mission . . . . I don’t wanna spoil it for you, Doug. Just rest assured, by the time it’s all over, you’ll have got the girl, killed the bad guys, and saved the planet.”

“You are what you do,” remarks the revolutionary leader Kuato (Marshall Bell) — a mutant encased within the body of another mutant named George; “a man’s described by his actions, not his memory.” It’s an existential credo given a troubling spin by the suggestion that Quaid’s attempts to fulfill Hauser’s instructions to defeat Cohaagen may be little more than manipulation at Cohaagen’s own hands –a metaphysical conceit that recalls the paradoxes of John Boorman’s Zardoz (1974), and raises the possibility that the whole movie itself may be a dream or memory implant, right down to the corny religious lighting of the grand finale (which is in many ways closer to De Mille than Spielberg). But is it Quaid’s dream or Quaid’s memory implant, or our own? With freedom and identity both matters of such perpetual doubt that not even a Schwarzenegger hero can circumvent it, the only thing one can really do is sit back and enjoy the show for what it is, expensive air and all.