Commissioned by The Chiseler, and posted there on July 4, 2020. — J.R.

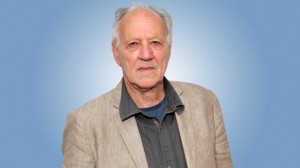

My first encounter with Werner Herzog was at the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in 1973, where I first saw Aguirre, the Wrath of God in an English-dubbed version that included, if memory serves, a few Brooklyn accents in 16th century Peru. (This is why it took some rethinking and retooling before the film could be successfully exhibited in the U.S., in German with subtitles.) But what flummoxed me the most — in spite of the film’s awesome visual splendor and its crazed poetic conceits — was what Herzog revealed about the opening intertitle when I asked him about it during the Q & A.

The intertitle: “After the conquest and sack of the Incan empire by Spain, the Indians invented the legend of El Dorado, a land of gold, located in the swamps of the Amazon tributaries. A large expedition of Spanish adventurers led by Pizarro sets off from the Peruvian sierras in late 1560. The only document to survive from this lost expedition is the diary of the monk Gaspar de Carvajal.” Herzog’s cheerful admission: the bit about the document and the diary was a total lie, invented by him because he reasoned that people wouldn’t accept the film’s premises otherwise. A cynical form of expedience, perhaps, but I’m sure he knew exactly what he was doing. His Family Romance, LLC(2019) — which MUBI is showing now for free, along with a Q & A with Daniel Kasman — proves that in spades.

For duffers like me who are too alienated from the business world to know what LLC means, it stands for “Limited Liability Company,” and the real limited liability company in Tokyo that this film is about rents out actors to play the roles of family members, friends, or diverse functionaries for lonely individuals — e.g., a divorced father whom a 12-year-old girl hasn’t seen since her infancy, or a bullet-train worker who needs to be shamed by his boss for bungling a precise train schedule, or a woman who once won a fortune in a lottery and compulsively tries to win one again, knowing she probably won’t, unless someone else pretends she does. The resulting feature has been described as a mixture of documentary and fiction, but as Herzog points out in his Q & A, apart from the company’s founder and (apparently) main actor, Yuichi Ishii, playing himself, the entire film is fictional — scripted and shot with a tiny camera by Herzog himself and with actors playing the various characters (including characters who are actors). A fair amount of this is implausible: I couldn’t buy the episodes with the bullet-train worker and the lottery winner, and the seeming intimacy of the scenes often seemed contradicted by the presence of a camera and the knowledge that someone was recording it. On the other hand, if one accepts the various segments metaphorically or philosophically rather than literally, not as real-life events but as postulates, the film becomes a fictional essay film, not a fiction that has to be truthful or even consistent.

This only scratches the surface of the existential games of deception and truth-telling being played, by us as well as by Herzog, because we sometimes have to perform a certain fictional role as spectators in order for the film to function. And because Family Romance, LLC obliged me to keep shifting my own performative role as a spectator, it kept me on my toes even when it failed to meet all my requirements for succeeding as either a sustained fiction or a cohesive essay.

For example, Herzog declares in his Introduction, “There was something big [about the business Family Romance, LLC] that I immediately sensed: where everything was fake, everything was done by impostors, everything was alive, everything was a performance, and yet the authenticity of emotions is always there. You can feel it right away. It is so intense that professional reviewers believed that the film must be a documentary, but of course it was all staged and written, rehearsed, and stylized.” Yes, but even if we decide that Herzog didn’t invent those “professional reviewers” in the same way that he invented the fake diary of Aguirre, what do we — even those of us who qualify as “professional” reviewers — mean by “authentic” emotions”? While the film’s score is being performed over dramatic scenes and/or transitional interludes (such as high-angle shots over the cherry-blossom park where the fake fake father and fake daughter meet), are the emotions that are being expressed and heard those of the composer, those of the musicians, those of the characters, and/or those of Herzog? Are they our emotions as well? Or are they maybe all of these–or is it only some of these that qualify as authentic, as opposed to inauthentic? How can we tell, and how can we be sure? We can’t truthfully or honestly answer any of these questions, and our ignorance on such matters becomes highly commercial — just as Herzog knows that claiming Aguirre derives from a historic document somehow makes it “authentic” even if we know perfectly well that it’s false. It’s really a matter of faith or else a suspension of disbelief. Either way, we need it even if we don’t believe it, and the bad faith that emerges from this dilemma informs a substantial part of our lives, leaking into many of its obscure corners as well as its principal thoroughfares. So one has to be grateful to Herzog for bringing this issue up, even if he arguably cheats on some of its implications — because we’re all cheaters when it comes to admitting our desires and then reconciling them with our practical lives.

For Herzog, as he expresses it to Kasman in his Q & A, the main issue isn’t the truth or falsity of what he’s showing but the essential loneliness of all the participants, in spite of (or maybe it’s because of) all the social media they depend on, which he sees as the essential characteristic of 21st century life. You might say that Herzog shares with Trump the conviction that lying and telling the truth are merely separate tools of equal value in contriving to get an audience to pay attention. Call it a form of media savvy; ethics don’t even play a part in determining which tool should be employed this time around. It’s a powerful position because it corresponds so closely to the ways that we prefer to lie to ourselves. The main narrative thread of Family Romance, LLC, also the most believable, is Yuichi Ishii pretending to be 12-year-old Mahiro’s long-absent father, and the scripted scene with actors that I find most convincing is the one in which the fake father discovers from the girl’s mother (that is, the actor playing the fake father pretending to discover from the actor playing the girl’s mother) that the photo Mahiro showed him of herself on a beach wasn’t photographed in Bali, as she claimed at the time, but on a local beach, which means that both of them were lying to one another. Like the multiplication of two minus signs, the cross-pollination of these two lies creates what appears to be an authentic truth. And of course appearances are everything.

I think it’s fair to say that the business conducted by Family Romance, LLC (meaning the company rather than the movie, although I suppose it can apply to both) is basically a form of nonsexual prostitution–which isn’t a value judgment, just an observation. After all, the sort of prostitution based on sex that involves a certain amount of make-believe also occurs inside some marriages. A filmmaker friend of mine once became a prostitute while preparing to make a film about prostitutes, and she told me at the time that she sometimes enjoyed her work, making men happy that way. Maybe she was conning herself in order to think that, but then again, so were some of her customers—and shared fantasies might be said to have certain claims on being real rather than imaginary. Insofar as reality is often a matter of social agreements, it can even be argued that social media — including your reading of this sentence — are one form of social reality, despite the loneliness Herzog finds in it. But social transactions are often carried out via symbols and icons —photographs, statues, flags, movies — that can be mistaken for their real-life equivalents.

Sometimes a prostitute’s client knows that (s)he is being fooled, sometimes not, but paradoxically even if (s)he does know, the issue of the prostitute’s authenticity matters — it comes with the territory. That’s where the bad faith comes in, in movies and in a good many other things. We all know that Charles Manson’s chicks weren’t wiped out by either stunt men or flame throwers and that Hitler didn’t perish inside a locked movie theater that went up in flames, but pretending otherwise makes a lot of people feel good. It even permits some of them to praise Tarantino for being sweet and gentle towards some of his other characters, including the murderers. It’s the same sort of thinking or nonthinking that enables our President to feel proud and happy about Confederate statues and selected or invented Coronavirus statistics making America great again, in the full knowledge that some of his followers will agree with him, sometimes without knowing what they’re agreeing about. When one of Family Romance, LLC’s clients, Mahiro’s mother, visits an Oracle, we don’t even know whether she believes in or plans to follow the Oracle’s advice; it’s simply a ritual act that she and we follow, like watching a movie and pretending that we believe in it.

It’s not too much to say that in different ways and to different degrees, we’re all happy and unhappy travelers on the bad faith express. It’s what makes life worth living and also what fucks us up.