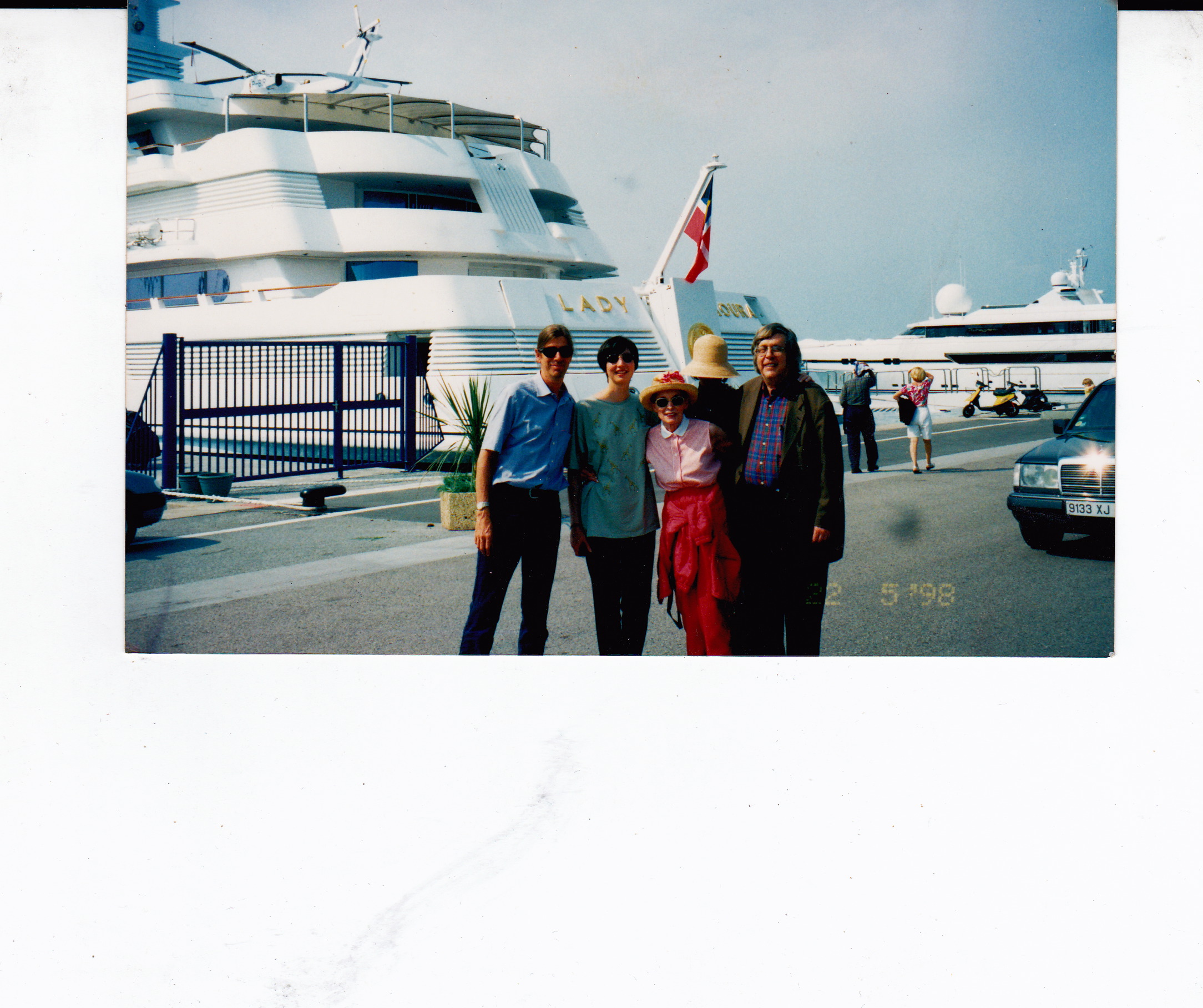

Reprinted from my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles, but with illustrations added. (The first of these is a photo taken near Antibes, France, where the revamped Touch of Evil was scheduled to premiere, until Beatrice Welles threatened a lawsuit and halted the screening. Much later, she sent a letter of apology to Janet Leigh that I got to read at one point. Fortunately, this didn’t prevent me from enjoying a wonderful day with Janet Leigh, her daughter Kelly, and several others on the Côte d’Azur, capped by this photo of the Touch of Evil re-edit “crew” and then followed by a memorable dinner.)

The following —- an account of my work as consultant for Universal Pictures on the re-editing of Touch of Evil in 1997-98, based on a studio memo -— is the only thing I’ve ever written for Premiere. I knew one of the editors, Anne Thompson, from her previous stint as assistant editor at Film Comment, and when I proposed this piece to her, she checked with other editors at the magazine and reported back that there was a lot of enthusiastic interest. When I asked her what approach I should take, she urged me to write a first-person account of my experience of the project from beginning to end, which yielded a first version. She reported back that I should interview Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, and Walter Murch and integrate some of this material. After doing this, I was told that the editors felt that a first-person account made the piece too much about myself and that the readers of Premiere couldn’t be expected to know anything about the film, so I should add a detailed plot summary without making the piece any longer. This second revision had to be cut further after the piece’s layout was done, eliminating practically all of the interview material. This is what appeared in their September 1998 issue.

When Peter Bogdanovich asked to reprint this article in the 1999 volume of The Best Movie Writing that he edited, I sent him the version printed below, but for reasons I’ve never understood, he opted for the skimpy published version instead. — J.R.

It all started with a book I was editing in the early 90s, This is Orson Welles, by Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich — an extended interview interlaced with various documents about Welles’s career. One of the most fascinating of these documents was an edited version of a 58-page memo written by Welles on December 5, 1957 after a single viewing of the studio rough cut of Touch of Evil, his last Hollywood picture. Addressed to Universal studio head Edward Muhl, the memo was a plea for certain changes in sound and editing in a cut that had been partially prepared in Welles’ absence, and although some of Welles’ suggestions were followed, many were not.

It was a rare glimpse into the strategies and motivations of a master filmmaker who usually preferred to keep silent about such matters. But This is Orson Welles was already a hefty volume carved out of thousands of pages and 25 hours of audiotape, and the memo was one of the key treasures that HarperCollins obliged me to cut due to lack of space. Eager to get it published elsewhere, I sounded out several film magazines, all of whom passed on it except for two small-circulation quarterlies on separate continents — Trafic in France and Film Quarterly in the U.S. — who printed it, respectively, in their spring and fall issues in 1992. I was delighted when, two years later, the Film Quarterly version prompted Charlton Heston, the star of Touch of Evil, to write me a cordial letter about it.

The same year, I received a phone call from the cinematographer Alan Daviau, who was exploring the possibility of a deluxe laser disc edition of Touch of Evil and mentioned the memo as something that might be relevant to the project. He also put me in touch with producer Rick Schmidlin, who eventually inherited Daviau’s project and then concocted a wild scheme out of it: to follow all the instructions in Welles’ 1957 memo for the first time. Then, after many more calls, Rick secured the agreement of Universal Studios, flew to Chicago to engage me as a consultant, and acquired Walter Murch — the celebrated sound editor of The Godfather, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, and The English Patient — to carry out the editing. Before long, the adventure was underway. (By happy coincidence, while some of this was happening, I was also persuading De Capo Press to include the edited memo in the second edition of This is Orson Welles, which came out last spring.)

During all this time I remained rooted in Chicago, joined umbilically by phone lines and mail routes to what Rick and Walter were doing in California — sending them various materials (articles, videos, radio shows) as stylistic reference points, putting Rick in touch with other Welles scholars, and meanwhile receiving the unedited copy of Welles’ memo, certain elucidating studio documents, and Walter’s rough cut on video once these became available. Apart from some brief stints as an extra for Robert Bresson and as a script consultant for Jacques Tati when I was living in Paris a quarter of a century ago, this was my first experience of working on a feature, and the first lesson I learned was that every decision made had multiple consequences.

At one point, Murch told me that it was like performing a skin graft using only skin from the same body, because none of the work entailed restoring lost footage; it was more a matter of different placements and configurations of existing shots, different uses of sound and music. Many of these changes were subtle, but virtually all of them had lasting reverberations that affected everything else — including the flow of the storytelling, the construction of mood and atmosphere, and the inflection of character and emotion.

It would be no exaggeration to say that no work of this kind has ever been done before — work that was neither a restoration nor a “director’s cut” in any ordinary sense, but delicate revamping based on executing postproduction instructions that had been drafted 40 years earlier. Interpretation of Welles’ requests was necessary, because no matter how straightforward they were, executing cuts and sound changes are never the same thing as describing them. And it was impossible as well as unthinkable to pursue what Welles might have wanted Touch of Evil to be in 1998. All we had to focus on was what Welles wanted in late 1957, which proved to be more than enough.

Originally released the following year in a 93-minute version that wasn’t even shown to the press, Touch of Evil enjoyed a brief second life when the 108-minute preview version was discovered in the mid-70s, containing more of Welles’ footage but also more footage shot by contract director Harry Keller during postproduction — a longer cut that has subsequently become the only one available (apart from the home video, which mixed parts of the two versions). Though the preview version has been erroneously labeled the “director’s cut” in some sources, the fact that Welles was never able to finish or approve any cut during his lifetime makes the very existence of such a thing a hopeful fantasy — more useful as a marketing tool than as an accurate description. Because Welles’ creative intentions were always in flux, predicated on what his existing options were at any given time, the most any posthumous cut can hope to achieve is an interpretation of what he wanted at one stage in that development.

***

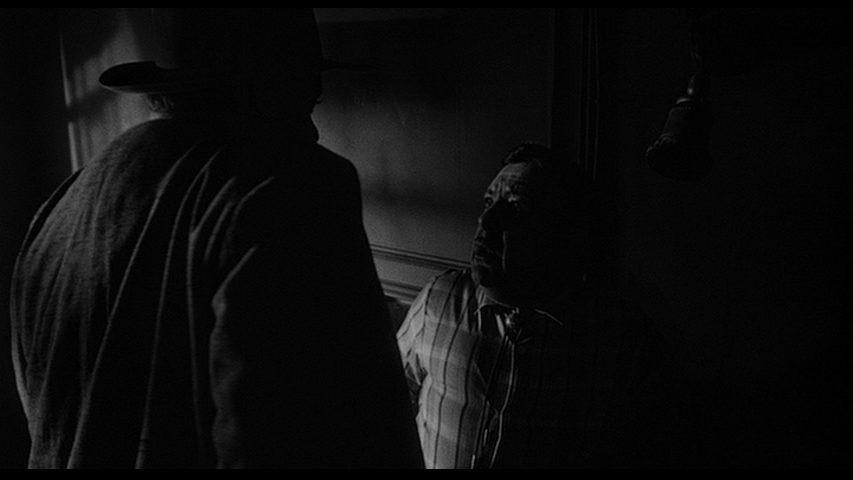

Aptly labeled “film noir’s epitaph” by Paul Schrader, Touch of Evil describes the dark events of one 24-hour period in a sleazy Mexican border town after a local businessman and his stripper girlfriend are blown apart by a time bomb planted in the trunk of their car. Though provisionally a mystery, the plot mainly focuses on the battle of wills between a Mexican cop named Vargas (Heston) who plays by the book and a crooked American cop named Quinlan (Welles) who plants evidence. The crime occurs within Quinlan’s jurisdiction, and Vargas is around at the time only because he happens to be there on his honeymoon. But by the end of the story, Vargas’s wife Susie (Janet Leigh), Quinlan’s partner (Joseph Calleia), and a local gangster (Akim Tamiroff) and prostitute (Marlene Dietrich) are all sucked into the conflict, along with many others.

The opening shot, one of the most famous in Welles’ career, is a dazzling crane shot that begins with the planting of the time bomb and ends several blocks away just before the explosion, taking in several other points of interest — including Heston and Leigh — en route. Included in the dense weave of the various paths taken by the camera, characters, vehicles, and extras, is an intricate crisscrossing pattern between the honeymoon couple on foot and the couple in the car as all four characters approach the border crossing and are checked through by a guard.

In all previous versions, this shot is accompanied by Henry Mancini’s score — which almost subliminally picks up the time bomb’s ticking in the bongos, generating a fair amount of Peter Gunn-like suspense — and overlaid by the film’s credits, which divert part of one’s attention from the unfolding events. In the new version, following Welles’ specifications, there are no credits over this shot and the only music one hears comes from loudspeakers in front of the various clubs and a car radio. Though the suspense is lessened, the physical density, atmosphere, and many passing details are considerably heightened, altering one’s sense of the picture from the outset.

“In retrospect and in hindsight,” Murch said after completing his work, “the changes we made have made the film more consistent with itself. That’s an odd thing for that film, because for all of its contradictions, it’s been admitted into the gallery of one of the memorable films of the 20th century. And yet it was a hybrid of what Welles wanted and did and what the studio left unchanged. So people who know the film have accepted it with all the stylistic contradictions in it and have forgotten or forgiven those contradictions. Now that they’re gone, in a sense it’ll be a shock because those who know it have gotten used to it the other way. It’s like when you jump on somebody else’s bicycle: it just feels different, the way the pedals work and everything.

“Stylistically the film uses crosscutting between different parts of the story — particularly Susie in the motel, what Vargas is going through, and what Quinlan is going through. Yet the studio, in an attempt to clarify the film in the opening reel, eliminated the crosscutting that Welles had intended as being too confusing. So once the explosion happens, except for that brief glimpse of Susie in the street, they stuck with Vargas and Quinlan for a continuous five or six minutes, and then they went to Susie. That wasn’t what Welles wanted and it’s not true to the rest of the film, which depends on crosscutting as a stylistic support for the story.

“So what we’ve done in the first reel — which is tremendously important as an overture to the whole work — is use more crosscutting. It’s better now because the opening reel is more like the rest of the film. That’s certainly true of the removal of the Mancini music from the opening shot and substituting a montage of various source music cues, which is also what Welles wanted.” Interestingly enough, this montage provides another kind of overture, strictly musical — an introduction to various elements in Mancini’s score that recur later.

One of the consequences of using more crosscutting is a stronger sense of different things happening simultaneously in the same border town. In a few cases the soundtrack has become more densely layered (as in the use of a Mexican newscaster on a car radio), and sharpening some of the sound cues, as requested, removes occasional incongruities, such as the immediate departure of musicians with their instrument cases from a strip joint as soon as the music stops playing. A superfluous patch of dialogue between Heston and Leigh in a hotel lobby that Welles neither wrote nor directed and which throws both their characters slightly out of kilter has been removed. A few frames are pulled from a frightening closeup of a strangled corpse, making its impact more subliminal. And a rapid editing pattern in the climactic confrontation between Vargas and Quinlan that was only partially realized in the two previous versions has finally been brought closer to Welles’ original design.

In many cases, when Welles didn’t fully explain his motivations in the memo, understanding why he dictated a particular change came only gradually, once the shot or scene could be seen and heard the way he requested it. Cutting the pianola music halfway through Welles’ first scene with Marlene Dietrich, for instance, made the whole second half of their dialogue play somewhat differently; lines that had previously teetered on the edge of camp mannerism suddenly came across as straight, and the whole scene ran more smoothly as a consequence. This in turn became part of Welles’ overall plan to use less musical editorializing in the opening reels that also occasioned the use of on-screen (as opposed to off- screen) music during the opening crane shot.

Eventually a clearer understanding of his design for the film began to emerge — a design that included, among other things, a more fluid narrative, more opportunities for certain atmospheric elements to register, and even a stronger sense of Quinlan’s partner Menzies (Joseph Calleia) switching his allegiances because of his moral principles rather than through any collapse in his willpower. The latter change came about through the removal of a single closeup of Menzies that Welles objected to in a scene with Vargas set in the Hall of Records; unfortunately, this deletion also meant losing a little bit of Vargas’s dialogue in order to avoid a jarring mismatch in the editing, but the gain arguably more than made up for the loss.

As far as Schmidlin, Murch, and I were concerned, the point of making all these revisions wasn’t to produce a “definitive” version that should necessarily replace or supersede all the previous ones. We simply wanted to see what happened when Welles’ wishes were carried out — nothing more, but also nothing less. Not his “ultimate” or “final” wishes, which no one could ever know or even presume to hypothesize, but his wishes as expressed on paper on December 5, 1957, shortly before he left the project.

***

“I think what you guys have done is admirable and does a great deal to make the film available,” Heston told me on the phone after seeing the revamped version. “What was most impressive to me was to have the whole sound track enhanced by the technology of the 90s. I’m really delighted with the work that’s been done on a picture that was important to me.”

Heston kept a diary for many years, and consequently in-depth accounts of the making of Touch of Evil can be found in two of his books, The Actor’s Life: Journals 1956-1976 and his more recent autobiography, In the Arena. Leigh also retain vivid memories of the experience, including the little-known fact that she broke her left arm shortly before she began work on the film while wrestling with character actor Jessie White on a TV drama called Carriage from Britain: “I had it set not at a right angle, which is normal, but halfway between a right angle and straight down, so I could drape a coat or purse or something like that over it.” She recalls that Welles originally thought of having her play Susie Vargas with her arm cast visible, but then concluded, “That’s too weird even for me: a bride on her honeymoon with a broken arm — I can’t do that!” So her cast was either concealed or briefly removed (for scenes when she wore a nightie), and no one in the audience noticed.

Fortunately, Leigh’s right hand was still free to write down lines of dialogue that she improvised at Welles’ house during two weeks of rehearsals prior to shooting: “A lot of the interplay between the characters came from improvising during the rehearsals,” she told me, and some of it cameduring filming as well, particularly her scenes with Tamiroff and Dennis Weaver (as a sexually deranged night clerk at the motel whose part barely existed in the original script). She remembers much of the shoot as a festive adventure: “I remember how the first night Marlene [Dietrich] worked, everybody had a bottle of champagne in their trailer. He did everything grandly; it was just a flair he had, and he didn’t care if you drank it. I didn’t happen to, but I’m sure he wouldn’t have cared if I did.”

For Leigh, the retouched Touch of Evil, which made her cry when she saw it, has “the original flavor more than the original released product did. Seeing it pure was wonderful; I was so thrilled that this genius is going to have a chance to show itself again.”