Posted on Artforum’s web site, 12/23/09. –- J.R.

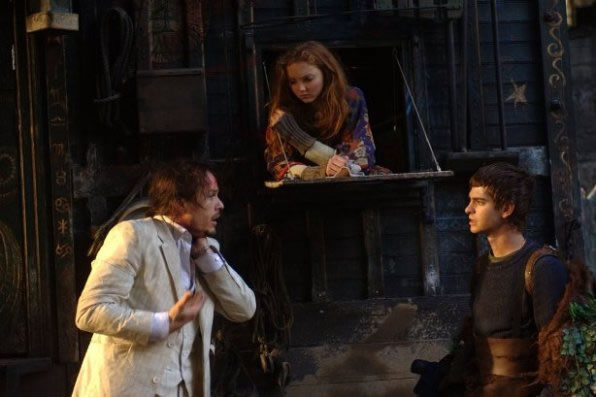

Terry Gilliam’s ambitious fantasy, The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus, set to open in the US on Christmas Day, already did well in some parts of Europe when it premiered there in October—notably Italy and the UK, where it placed third during its opening weekends in both countries. I saw it the first time myself in Saint Andrews, Scotland, with an appreciative audience in early November. The lead character, Tony — played by the late Heath Ledger and three other actors (Johnny Depp, Jude Law, and Colin Farrell), who were called in when Ledger died halfway through the filming — is partly conceived as a spoof on Tony Blair, though one wonders whether this conceit will register with much clarity for the American audience. But it’s also unclear how much this will matter, given all the other points of attraction (such as Tom Waits as the devil and Christopher Plummer as the Methuselah-like Parnassus). Far more relevant, it seems, is the way Gilliam has ingeniously adapted the avant-garde multiple-casting ploy of everyone from Yvonne Rainer (Kristina Talking Pictures [1976]) to Todd Haynes [2007]) in terms of his own mainstream fantasy plot.

Roughly speaking, for both its postmodern mishmash of periods, locales, and styles and its metaphysical ambiguities about age and identity, Gilliam’s postmodernist salad belongs in the special company of Hayao Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle (2005) — the most commercially successful domestic release in the history of Japanese cinema, almost completely ignored in the US for what I suspect were partially ideological reasons. (Apart from his antiwar sentiments, Miyazaki’s unorthodox vision in which old age and youth, callowness and wisdom, peacefully coexist rather than succeed each other is no less challenging.) To a lesser extent — more a matter of design than of spiritual depth — it also shares a certain imaginative freedom with Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, released the same year, which by contrast placed eighty-seventh in one of Boxoffice magazine’s two recent “all-time” lists of the most commercially successful American releases (the one unadjusted for inflation).

Will The Imaginarium’s stateside fate be closer to that of Miyazaki’s parable or to that of Burton’s less coherent meditation on class difference? As storytelling it’s harder to track than either of those 2005 features, but its seductiveness as a digital smorgasbord is more apparent, and it’s even profitable to view these two qualities as interrelated. Gilliam’s orientation as a former comic-book artist is basically that of a hippie bricoleur whose concepts seem to grow out of his images rather than vice versa. Even if The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) sporadically calls to mind Calvino’s Cosmicomics (1965) as much as his Brazil (1985) echoes Orwell’s 1984 (1949), one often feels that the graphic designs in Gilliam’s films supersede (and perhaps even yield) the literary concepts.

More relevant here is The Imaginarium’s parallel collapsing of diverse historical eras and various kinds of flat and three-dimensional space under the same old-fashioned proscenium, reeking of a nostalgia for nineteenth-century English traveling players planted in some version of both contemporary London and its postapocalyptic future, a mix already evident in the opening shot. The Imaginarium — an elastic space behind or through an onstage “mirror” occasioning both the film’s best digital effects and its multiple casting of Tony — might be compared with both the title talisman in Balzac’s 1831 novel La Peau de chagrin (a wild ass’s skin that gratifies the desires of its owner, progressively shrinking — along with the owner’s life force — every time it is used) and the more abstract and metaphysical Zone in Tarkovsky’s 1979 Stalker, which is bit closer to a kind of spiritual Rorschach test for anyone who tries to enter it. (Still another cross-reference might be Charles G. Finney’s 1935 novella The Circus of Dr. Lao.) But the metaphoric significance ultimately pales beside the “Open, sesame” it offers to Gilliam’s free-form improvisations.