From the Chicago Reader (May 17, 2002). — J.R.

La Commune (Paris, 1871)

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Peter Watkins

Written by Watkins with Agathe Bluysen and contributions from the cast members.

Some filmmakers say this is my work and I want it to stay that way. That is their right, and we respect that right. Those are the films we don’t buy, and those are the films we don’t transmit. — TV executive in The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins

I’ve been a fan and supporter of Peter Watkins for most of my life. A remarkable master technician and social visionary whose early work is filled to the brim with focused rage, he has created some of the most troubling, thought-provoking, even shattering films I know. This has helped make him persona non grata in mainstream TV and cinema and also in art houses, among academics, at festivals, and on cable TV. When his name does come up in those diverse realms, he’s often accused of being paranoid — though that hardly explains his pariah status.

Keeping up with his work is hard even for a sympathetic critic like me, and I can’t say I know it well. I was blown away by his first theatrical feature, Privilege (1966), which imagined a fascist takeover of Britain and a puppet rock star (played by Paul Jones) used to galvanize the masses. That sent me back to two mind-boggling BBC films, Culloden (1964) and The War Game (1965), and then on to his next two features, The Gladiators (1968) and Punishment Park (1970). Neither was as strong as Privilege, but the anger and sense of desperation in both seemed just as potent. Like his preceding works, they had the courage to imagine the worst things possible and to refuse to make them palatable in any of the usual ways–with characters who are easy to identify with or with messages that are easy to digest. At their worst, they had the sort of monotony one associates with most monomaniacal works, rarely deviating in tempo or emotional tone, but they still said things no other films were saying, with passion and force.

Nevertheless, as a writer in Le monde put it in 1971 without much hyperbole, “To find traces of Peter Watkins in a dictionary or a history of cinema you might as well hire a private detective. His works remain hidden, or forbidden, in most cases.” Watkins’s much more commercially successful, if uncharacteristic, biopic Edvard Munch was released in 1976, but his other work has become even less accessible since then. (I have yet to find a way to see The Freethinker, his 1994 feature about August Strindberg.) His marginalized status seemed only to intensify his intransigence, which made it even less likely that his films would be screened or seen. For instance, his highly ambitious documentary about the global peace movement, The Journey — made in the mid-80s and running over 14 hours — has shown mainly at festivals; to see it at one typically would mean missing six or seven other films. As a result I haven’t seen any of it so far.

His latest magnum opus, La Commune (Paris, 1871) (1999), runs only five hours and 45 minutes, but I missed it at Toronto and Rotterdam, and saw only part of it in Buenos Aires last month (I saw the rest on video here; it’s playing at the Gene Siskel Film Center in various two-part installments this week). I was surprised that the auditorium in Buenos Aires was as packed for the later portions as for early ones and that the audience was absorbed in all the details. I also managed to see a feature-length documentary about La Commune made by Geoff Bowie for the National Film Board of Canada, The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins (unfortunately not being screened in Chicago) — a film that enlightened and confused me by at times sparking my interest even more than Watkins’s pseudodocumentary about the Paris Commune of 1871.

It probably isn’t surprising that Argentineans would find La Commune engrossing, given the crisis in their economy and society and their hunger for new ideas. If you don’t know much about the Paris Commune, which lasted a little less than two months, you shouldn’t feel left out; according to Watkins, even most French people don’t know much about it — which is part of what motivated this massive project. In broad outline, on March 18 — during the last days of the Franco-Prussian war, while Parisians were enduring massive unemployment and the effects of the Prussian siege of Paris — the left-leaning Paris National Guard revolted, took over the town halls of most of the districts of Paris, and executed two of the provisional government’s generals after its head, Adolphe Thiers, tried to seize one of the national guard’s cannons in Montmartre. (Women in the district persuaded the government soldiers not to fire on Parisians, and their appeal helped spark the insurrection.) Thiers and his government fled to Versailles to join the recently elected monarchists of the national assembly; they became known as the Versaillais. A week later the national guard held new municipal elections, and the socialist-anarchist Commune was installed at the Hotel de Ville; it introduced radical social reforms while fending off the advancing Versaillais. The reforms included setting up a new educational system that separated church and state, instituting professional education for women, giving pensions to unmarried women, suspending or canceling many debts, establishing unemployment exchanges, abolishing night work for bakers, and allowing trade unions and workers’ cooperatives to take over abandoned factories.

Within two months the Versaillais had amassed an army of 300,000 soldiers, which reentered Paris on May 21, plowing through the communards’ street barricades and massacring between 20,000 and 30,000 Parisians over the course of a week. The nearest contemporary equivalent to this brief utopian moment ending in bloody tragedy might be the demonstrations at Tiananmen Square and the subsequent government crackdowns in the spring of 1989.

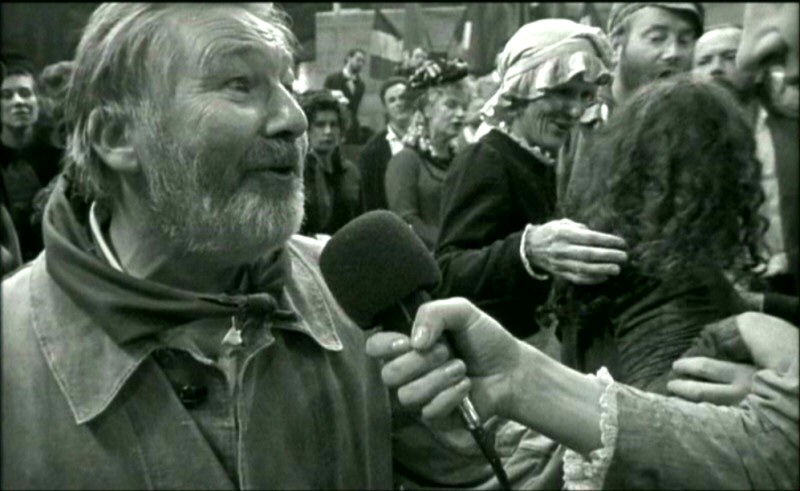

Before filming, Watkins and his production team did months of research, cast more than 220 French and North African people from Paris and the provinces (most of whom had no previous acting experience), and asked them to do their own research on the 1871 Commune and collaborate in the creation of their characters and the writing of their dialogue. (At a later stage the actors formed separate groups based on the characters they were playing — the women’s union, the national guard soldiers, the middle-class characters opposed to the Commune, the elected members of the Commune, the Versaillais forces, the members of a convent — to discuss the backgrounds of those they were portraying.) Through the conservative press, right-leaning Parisians were recruited to play the Versaillais — part of the plan being to create a psychodrama that would explore relationships between the historical event and the present. The film was shot on black-and-white digital video over a mere 13 days in an abandoned factory in Montreuil, where the studios of film pioneer Georges Melies once stood. Much of the shooting was done in long takes, with a lot of camera movement. Close-ups are few and far between; most of La Commune is in medium shot, typically with several characters in the frame.

Watkins’s The War Game (1965), probably his best-known film — a terrifying 47-minute pseudodocumentary that imagines the immediate effects of a nuclear strike on Britain — won a well-deserved Oscar for best documentary, yet it was banned from worldwide TV broadcasting for 20 years by the BBC, which rationalized its suppression by calling it an artistic failure. That only encouraged supporters to be hyperbolic. Kenneth Tynan, probably the greatest theater critic of the second half of the 20th century, saw it at a private screening and wrote in the London Observer, “I suspect that it may be the most important film ever made. We are always being told that works of art cannot change the course of history. Given wide enough dissemination, I believe that this one might….The War Game is more than a diagnosis; it is a work of art. It precisely communicates one man’s vision of disaster, and I cannot think that it is diminished as art because the vision happens to correspond with the facts. Like Michelangelo’s ‘Last Judgment,’ it proposes itself as an authentic documentary image of the wrath to come — though Michelangelo, of course, was working from data less capable of verification.” Watkins’s gargantuan Web site (www.peterwatkins.lt; he’s now based in Lithuania, where his Lithuanian wife works as a freelance translator and editor) quotes portions of this review and several others, positive and negative, though it fails to cite Tynan by name — just as it fails to cite the names of most of the actors in his films.

Like many other Watkins films — including The War Game, Punishment Park, and the brilliant Culloden (which chronicles the last land battle fought in Britain, in 1746) — La Commune is basically done as TV reportage. That sounds like an odd way to treat events in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it actually works as a way of commenting on both history and the present, social memory and the media. Watkins emphasizes rather than soft-pedals the anachronisms, encourages his actors to look at the camera, and incorporates two competing TV channels that report on what’s happening from the communard and Versaillais viewpoints just as contemporary talk shows and news programs do.

Unlike much of Watkins’s early work, La Commune isn’t particularly disturbing most of the time, though its length makes it somewhat unwieldy, even intractable — a length that wouldn’t be an obstacle if it were a TV miniseries. La Sept ARTE, the French-German TV consortium that produced La Commune, broadcast the film only once, from ten at night to four in the morning — arguably a form of suppression, unless people set their VCRs to tape it while they slept. Since then it has been taken out of its natural habitat, television, and distributed as a film (though the Film Center is presenting it on Beta SP video). A shorter, 270-minute version was prepared specifically for theatrical screenings, though to the best of my knowledge it has yet to be shown. Conceived as television, La Commune has been repackaged and mislabeled, and is now being misperceived as a feature film — something I’m complicitous in because I’m agreeing to review it as one.

Why is La Commune 345 minutes long? Watkins admits on his Web site that it was originally planned as a two-hour feature, implying a shift in his own strategy from film to TV. But, he notes, “the method of filming long sequences expanded the internal construction of the film to the point where it became impossible to reduce it beyond a certain stage during the editing, without destroying the very process which had developed in the filming.” The final phrase seems crucial: shot with the participation of the 220 cast members, La Commune is in some respects more significant as a production experience for those individuals than as a viewing experience for us. This has understandably led some people to dismiss or devalue the film as a viewing experience, but whether one finds it gripping or tedious depends almost entirely on one’s expectations and one’s emotional as well as intellectual relation to the subject. (This isn’t discussed often enough, but what we find absorbing on TV might be boring in a movie auditorium and vice versa.) If one senses and can relate to the importance of the film’s production for its participants, it can certainly be mesmerizing for long stretches. That the quality of the acting is extremely variable counts for little, because whether the actors are good or bad, they’re every bit as interesting — and as important to the work’s overall conception — as the characters they’re playing.

I suspect that Watkins’s many years in the wilderness, cut off from any form of mainstream support or exposure, has led him to value the production of his work as an educational process for everyone involved more than its reception. This is probably why I prefer Bowie’s documentary about it — because it shows in detail how meaningful and exciting the making of La Commune was for both the actors and Watkins, who can be seen barking his instructions in French during the crowd scenes with the frenetic energy of a conductor like Leopold Stokowski.

In the latter part of his career Orson Welles seemed on occasion to prefer making films to having them released — especially Don Quixote, which was financed out of his own pocket (he may have felt the same way about some of his protracted work on The Other Side of the Wind, much of which also took the form of a pseudodocumentary). He’s been widely criticized for this tendency, but it’s easy to understand his motivations given the joy he and his collaborators often felt while making his films and the often hostile critical reception the films met when they were released. Like Welles, Watkins made a controversial splash at the beginning of his career, then suffered a comparable marginalization, and it’s easy to see how the nearly insuperable problems he’s faced in getting his works shown may have reduced the importance of their reception. Why not stretch a two-hour movie to six if this gives more pleasure, edification, and inspiration to its participants, especially if one concludes, consciously or unconsciously, that it won’t be widely distributed anyway? (A large part of The Universal Clock is devoted to the tragicomic futility of trying to interest television outlets across the planet in works such as La Commune, whose availability is often in inverse proportion to their seriousness. In contrast are the Ken Burns types, who seem ready to compromise anything and everything — their subjects, their intellectual, political, and aesthetic integrity — for the sake of their formats and audiences.

I’m fascinated by the way that Watkins — like Kevin Brownlow, whose two features showed here two years ago — seems equally preoccupied by history and science fiction, regarding each as a different kind of sustained speculation. (The same sort of dual vision is apparent in Stanley Kubrick’s oeuvre if one places, for instance, Barry Lyndon alongside 2001: A Space Odyssey.) Brownlow’s first feature, It Happened Here (1966), imagined England losing World War II, and his second, Winstanley (1975), imagined the failure of a real-life nonviolent religious sect called the Diggers to establish a commune in Surrey in 1649. Watkins’s fascination with the failed Paris Commune is infuriating to many orthodox Marxists and Trotskyites (see, for instance, David Walsh’s review in the December 2001 issue of Cinema Scope), much as Winstanley was — because he fails to honor or validate either side of the cold war, or any of the fashionable historical theories in academia, for that matter. Karl Marx, for example, gets mentioned only once. In fairness to Walsh, Watkins’s approach may not always be good history; he’s more interested in finding the relevance of the Paris Commune for Parisians today, most of whom aren’t historians either.

In other words, La Commune isn’t so much a realistic re-creation of anything as it is a dialogue between past and present, with each time frame used to shape and define the other. The film begins with a long title explaining part of the historical context, followed by a moving camera’s endless inventory not of the district where all the action takes place, but of the set representing it, street by street and shop by shop. The shooting of the action has just been completed, and a couple of actors in costume introduce themselves as two of the news reporters; then we get glimpses of members of the film crew in their normal street clothes, then a narrator telling us about both the aftermath of the film shoot and of the massacres that ended the Commune. (The mobile camera inside a studio setting vividly recalls the style of live TV dramas of the 50s such as Studio One.)

Then comes the story proper. But it soon becomes evident that the story proper exists in all the factual as well as fanciful stages separating us from the dream, the experience, the challenge, and the failure of the Commune, steps that lead us directly from our own world to that other one we call history — which proves to be our own world as well. (Eventually we get discussions by the actors speaking for themselves about contemporary conditions and printed titles that move beyond 1871 to discuss such current matters as the monopolistic stranglehold American cinema has on Europe and South America.) One may miss the poetry of the neglected but revolutionary classic Russian silent movie with the same subject, Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg’s The New Babylon (1929), but there are plenty of compensations, most of them very contemporary in feeling. And the film is a cosmos away from the latest Star Wars installment, which implicitly invites us to contemplate, even savor, the prospect of The Gulf War, Part II and the stamping out of a few more ugly and unruly Middle Eastern insects. But then Watkins’s view of the past is a far cry from “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away…” This Commune exists now, around the corner, and he dares us to step in, take sides, and this time do a better job of dealing with the Versaillais. Yeats put the best spin on this matter, for all concerned: “In dreams begins responsibility.”