From the Chicago Reader (August 27, 2004). — J.R.

The Blonds

*** (A must-see)

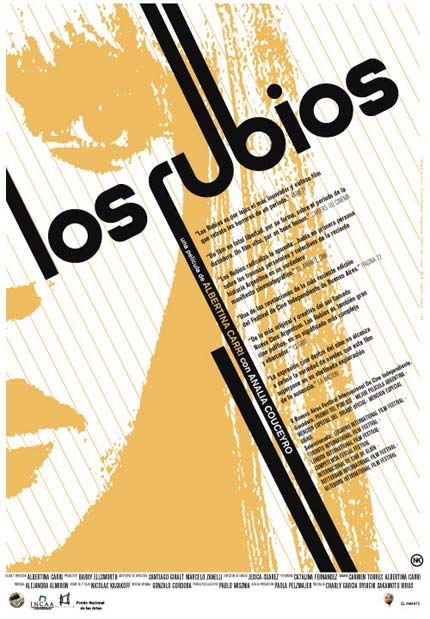

Directed and written by Albertina Carri

With Analia Couceyro.

Rosenstrasse

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Margarethe von Trotta

Written by Pamela Katz and von Trotta

With Katja Riemann, Maria Schrader, Martin Feifel, Jurgen Vogel, Jutta Lampe, Doris Schade, and Fedja van Huet.

It was a severe disappointment, Beyle [Stendhal] writes, when some years ago, looking through old papers, he came across an engraving entitled Prospetto d’Ivrea and was obliged to concede that his recollected picture of the town in the evening sun was nothing but a copy of that very engraving. This being so, Beyle’s advice is not to purchase engravings of fine views and prospects seen on one’s travels, since before very long they will displace our memories completely, indeed one might say they destroy them. — W.G. Sebald, Vertigo

I don’t know if some memories are real or if they’re my sisters’. –Albertina Carri in The Blonds

When I was in junior high school in the 50s I associated Stanley Kramer’s name — first as a producer, then as a producer-director — with offbeat, somewhat worthy highbrow ventures such as Cyrano de Bergerac, Death of a Salesman, High Noon, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T., The Wild One, and The Caine Mutiny. Lots of people did. Liking these mainly black-and-white movies could be a snobbish badge of small-town sophistication, roughly akin to subscribing to the Saturday Review, and I was as susceptible to this as anyone.

By the time of The Defiant Ones (1958), On the Beach (1959), Inherit the Wind (1960), and Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), my respect for Kramer had sunk. I could see how he’d conflated art with education and other self-conscious middle-class ideals, making him a little dubious as a gray eminence. And I saw those movies’ smugness and self-righteousness and the lack of imagination in his directorial style. I started to look at these films as reprehensible, tantamount to antiart statements.

I expressed my distaste for Judgment at Nuremberg to Bertha, a Russian emigré living in my Alabama hometown who went to the same Reform Jewish temple as my grandfather and who drove him and others crazy with her procommunist opinions. She thought it was the greatest movie ever made, and she told me indignantly, “You’d feel different if Hitler slaughtered most of your relatives.” In other words, the movie’s subject matter made any question about art or emphasis irrelevant — the same judgment some people later made about Schindler’s List.

Bertha apparently thought the hokey star turns by Judy Garland, Montgomery Clift, Burt Lancaster, Spencer Tracy, and Maximilian Schell in Judgment at Nuremberg did the job of bearing witness to the Holocaust. She didn’t have the option then of seeing Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (1956), Hiroshima, mon amour (1959), or Muriel (1963). Like Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 Shoah, these films implicitly argue that morally apt and honest representations of historical atrocities such as the Holocaust, the dropping of the atomic bomb, and the torture of Algerians aren’t easily arrived at.

The issue isn’t whether atrocities are shown; it’s the attitude toward them. One might also question whether the past is ever truly knowable, especially given all the entertaining and photogenic substitutes for it that keep coming along. The etching of the town that interfered with Stendhal’s memory of the place has a parallel in Kramer’s or Steven Spielberg’s aggressive image replacements. By contrast, Resnais and Lanzmann are concerned with the sense of absence created by images even when they purport to tell us everything. Night and Fog, unlike Shoah, shows us concentration camp survivors and corpses, Hiroshima, mon amour gives us actual and restaged evidence of the bomb’s effects, and Muriel offers a long verbal account of torture but refuses to show us any of it. The key line in Marguerite Duras’ script for Hiroshima, mon amour, spoken by the Japanese hero to the French heroine, his lover, immediately undercuts all the real and ersatz newsreel footage: “You know nothing of Hiroshima.”

I don’t mean to limit this distinction, which is essentially moral, to one between Hollywood movies and art films. Samuel Fuller’s most ambitious war movie, The Big Red One (1980) — coming in a recent reconstruction to the Chicago International Film Festival in October — straddles these categories, implying both that the violence of war can be shown and that it can’t. Fuller believed in most Hollywood conventions, but he believed even more in his own combat experience during World War II, and he realized that sometimes the former were inadequate when it came to representing the latter. Schindler’s List can be seen as a Hollywood movie or as an art film, but either way Spielberg seems as untroubled about the task of representing the Holocaust as Kramer was.

We like to think we’re more thoughtful about such matters today than we were a half century ago, but I wonder. Albertina Carri’s The Blonds (2003), a provocative Argentinean feature playing this week at Facets Cinematheque, deals with the filmmaker’s efforts to uncover information about her leftist parents, kidnapped and murdered in 1977, when she was only four years old, during Argentina’s “dirty war.” Her film’s a lot closer to Shoah than to Judgment at Nuremberg. (This is why I can’t imagine it turning up in the ultraconventional Chicago Latino Film Festival.) It’s won significant acclaim and recognition in Argentina even though it refuses to offer the comfort and certainty of a conventional documentary — something that has alienated part of the mainstream press. “Too much of the film is in a mood of chin-scratching detachment,” complained A.O. Scott in the New York Times, “and this creates a vacuum in which its powerful, confrontational moments lose their force, the trauma of the past pushed nearly out of reach.”

In many ways Carri is even more avant-garde than Lanzmann or Resnais. She hired an actress, Analia Couceyro, to play herself in the present, walking around her old rural neighborhood and interviewing people about their memories of four-year-old Albertina, her two older sisters, and her parents. But she never allows us to forget that we’re watching an actress, and periodically shows herself directing Couceyro, sometimes in successive takes. She also reflects on the seemingly insuperable obstacles she faces in recovering as well as representing her past: “My sister Paula doesn’t want to appear on camera,” she says at one point. “Andrea does, but she says all the important things when I turn the camera off.” Later she says, “All I have are vague memories contaminated by so many versions.” On other occasions, she offers us animation — Lego toys in front of a dollhouse that represent her family and various animals in the neighborhood when she was four, sometimes accompanied by relatively realistic voices.

When big Albertina asks the neighbors about little Albertina, it’s not always clear whether Couceyro or Carri is asking the questions; most of the neighbors remember next to nothing, so Analia can easily stand in for Albertina. What they do remember often seems unreliable. One woman recalls that everyone in the family was blond — the source of the film’s title — but we see and hear nothing to support this claim. Then, very late in the film, we see Couceyro, Carri, and various crew members walking around the neighborhood in blond wigs, suggesting that maybe Albertina’s true family is her team of collaborators.

For her scruples Carri seems to be paying a hefty price — a limited audience outside Argentina. No such price is being paid by Margarethe von Trotta, whose highly conventional Rosenstrasse opens this week at mainstream venues. This movie deals with the little-known protests of Aryan German women married to Jewish men who were held by the Gestapo in a building on Berlin’s Rosenstrasse in 1943. There aren’t any Hollywood star turns, but the glitzy period re-creation glories in the kind of burnished arty look The Conformist and later the Godfather movies made famous, and von Trotta isn’t shy about playing up the tear-jerking elements. Her fictional story is also about a little girl losing her parents, told as a series of flashbacks from the present, when the daughter of a Jewish Holocaust survivor in Manhattan interviews the non-Jewish German woman in Berlin who briefly raised her mother. Most of this is rather muddled, because the daughter wants to understand why her mother objects to her marrying a non-Jew, and what she discovers by way of explanation is how her mother’s life was saved by a non-Jew. Everything seems to get sorted out by the end, but more for the characters than the audience.

Conventional wisdom would say that von Trotta’s film comes from and speaks to the heart and Carri’s comes from and addresses the head. But I think Carri’s quest is largely a search for her own identity, and her avant-garde methods derive mainly from gut instinct. Experimental filmmaker Yvonne Rainer has frequently cast several actresses to play herself or her autobiographical heroines in tandem, clearly concluding that using a single actress would be some form of cop-out. Stanley Kwan’s ravishing biopic Actress (1991), about Shanghai silent-film actress Ruan Ling-yu (Maggie Cheung), also refuses to limit its journey into a lost past to either fiction or documentary, choosing instead to acknowledge that both are problematic.

Carri may well have created so many difficulties for herself and the viewer because she had no choice, at least if she wanted to remain honest. But there are gains as well as losses. As writer and filmmaker Edgardo Cozarinsky puts it, “The film avoids the solemnity and ideological simplifications common to many cinematic treatments of the desaparecidos.” The real subjects are “the impossibility of compensating for such a lack, the brutal severing of family ties, memory’s search for facts — and unstoppable fictionalization of what it finds.” Yet as one hilarious sequence shows, the film initially failed to get state funding because Carri’s murdered parents were intellectuals and she insisted on interviewing their neighbors rather than more “important” figures — i.e., other intellectuals. (We see the film crew reading aloud from the bureaucrats’ snobbish letter.)

Von Trotta, who’s obviously less personally invested in her story, seems more than a little calculating in her efforts to wring tears. It doesn’t seem unreasonable to conclude that, like Kramer, she’s interested first in addressing a wide audience and second in teaching a history lesson. Yet the sort of lesson she has in mind, like Kramer’s and Spielberg’s, includes a certain amount of uplift and closure — and so becomes a kind of tranquilizer that frees us from the burdensome task of trying to remember the past in all its ambiguity.