From the Chicago Reader (July 8, 1994). Also reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

** FORREST GUMP (Worth seeing)

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by Eric Roth

With Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, Sally Field, Michael Humphreys, and Hanna Hall.

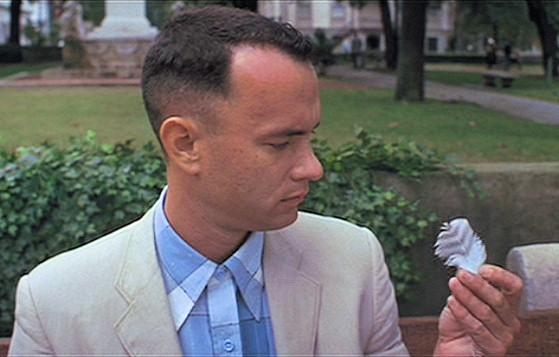

In the opening shot of Forrest Gump — a movie that might be described as Robert Zemeckis’s flag-waving Oscar bid — the camera meticulously follows the drifting, wayward trajectory of a white feather all the way from the heavens to the ground, just beside the muddy tennis shoes of the title hero (Tom Hanks). Forrest Gump, a slow-witted, sweet-tempered, straight-shooting fellow from Alabama with an IQ of 75, is waiting for a bus in a small park in Savannah, Georgia. Picking up the feather and placing it inside a book, he proceeds to recount his life story to various passing strangers; in the film’s final shot, over two hours later, we see a breeze carry the same white feather up and away.

These framing shots — a poetic statement about the vicissitudes of chance, how histories are made, unmade, and remade — are meant to say something about a half-century of American life, from the 40s to the present; and the tragicomic life of Forrest Gump, a saintly fool, is meant to embody those years. How curious, then, that one irresistibly focuses on the careful, deliberate way Zemeckis has plotted the feather’s seemingly arbitrary progress — and on how calculated and contrived Gump’s supposedly absurdist story turns out to be. Figuratively the feather being blown around is us, not Gump or American history. What’s blowing it around is a Hollywood wind machine exuding hot air, and what’s guiding its trajectory is an invisible wire pulled by a puppet master.

“Of all the forms of genius,” Thornton Wilder wrote in The Woman of Andros (1930), “goodness has the longest awkward age”; five years later he made this the epigraph for his Heaven’s My Destination, a novel about another saintly fool. The figure whose moral purity leads to endless comic complications is also a staple in many of Frank Capra’s best-known movies — and is central to Leo McCarey’s underrated Good Sam, which can be read as a sort of dialectical response to Capra. In fact it’s a tradition in American thought extending well beyond the movies: Forrest Gump has many literary precedents apart from the novel by Winston Grooms (which I haven’t read) on which Eric Roth’s screenplay is said to be vaguely based. One can trace related fancies in the ironies of Jewish novelists such as Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud (both of whom undoubtedly influenced Woody Allen’s Zelig, one of Forrest Gump‘s more obvious sources) and in the whimsy of Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Joseph Heller, and other “black humor” novelists. Benjy, the literal idiot who narrates the first section of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury, offers an even stronger (but less comic) analogy.

One is tempted to say, with apologies to Wilder, that of all the myths of innocence that have spurred this country on, from George Washington to O.J. Simpson, the myth that innocence is goodness (and vice versa) has surely had the longest awkward age; we haven’t yet outgrown it. Even Wilder and Faulkner bought into it, and it still dictates not only a good deal of our literature and movies but much of our foreign policy. From beginning to end, Forrest Gump plays this myth like a grand organ.

I can’t say I wasn’t moved. The sweetness of Tom Hanks’s performance, and Zemeckis’s mastery as a storyteller and technical wizard, can’t be denied. If the movie were less skilled and effective, I’d have less reason to feel such rage about what it’s doing. (Viewers who don’t want any surprises given away are urged to check out at this point.)

Born in the mid-40s, Forrest Gump is raised by a devoted, resourceful single mother (Sally Field) who runs a boardinghouse in the remote imaginary town of Greenbow, Alabama. Speaking as someone born in a small town in Alabama around the same time, I find little about this town and the surrounding terrain believable (in fact the Greenbow sections and those set in Vietnam were both filmed in South Carolina). But for Zemeckis’s purposes, this is of no importance; it’s the mythical south he’s aiming for and achieves. Fitted with leg braces by a doctor who declares his back to be “as crooked as a politician,” Forrest is an outcast from early childhood on, befriended only by a poor classmate named Jenny (Robin Wright). Sexually abused by her father, she has even more misery to contend with than he does. Jenny, who dreams of being a singer like Joan Baez, becomes by turn a stripper in a Nashville dive, a flower-child hippie with ties to the Black Panthers and the antiwar movement, and a cokehead; it’s typical of the movie’s tacit emotional connections that we’re somehow made to feel she’s been driven into all these things by the abuse she’s suffered. Those connections are also a good example of how this “apolitical” movie takes a stand on such issues as the 60s counterculture. And the reason Zemeckis can get away with this and many related ploys is that Jenny and Forrest’s “history” is merely the version of it propounded on and ratified by TV.

Back in Greenbow, before Jenny has all these adventures, she counsels Forrest to run as fast as he can from a gang of bullies; eventually he becomes such a good runner that he gets a football scholarship to the University of Alabama. It’s about the same time that George Wallace is trying to block integration there, occasioning one of the many Zelig-like special effects in which Forrest appears in TV news footage. (Earlier Forrest is shown innocently “teaching” one of his mother’s boarders, Elvis Presley, how to shake his hips before he appears on The Ed Sullivan Show, and one of his ancestors, a Ku Klux Klan general, can be glimpsed in a clip from The Birth of a Nation.) Subsequently Forrest shares the small screen with John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Dick Cavett, John Lennon, and Richard Nixon, among others, as he becomes first a football hero, then a war hero, and finally an international ping-pong champion.

Apart from their varying effectiveness as gags, these visual stunts, unlike others in the movie, are technically shoddy. The lip movements of the famous people in the original footage have been grotesquely altered — a technique also used in the hideous Speaking of Animals shorts of the 1950s, in which zoo creatures would turn to the camera and deliver pithy one-liners — and the dubbing in of punch lines by vocal impersonators is imprecise. As part of the film’s implicit ideology, however, these gags are essential. For one thing, they trade on the sound-bite and image-bite TV concept of history: Forrest exposing the war wound on his buttocks to LBJ alludes directly to LBJ revealing his surgical scar to the public — the only thing about Johnson deemed historically significant here. These stunts also create a sense that history is absurdist and accidental rather than willed: the film ascribes the discovery of the Watergate burglary to Forrest, in essence feeding the alienated couch potato’s triumphant sense of one-upmanship, as in much of Zelig or in Indiana Jones and the Lost Crusade when Jones gets Hitler’s personal autograph. Finally, these spots create the equally comforting sense that sharing media space puts everyone on the same level: U.S. presidents are “celebrities” just like Cavett and Lennon. In much the same way, sexual abuse and AIDS in this movie become discrete little nuggets of American history, along with various bumper stickers (“Shit happens”) and T-shirts (“Have a nice day”), the civil rights movement, the 70s popularity of jogging, familiar pop tunes, and the attempted assassinations of Wallace, Ford, and Reagan. TV, the great leveler, brings them all together, like acts on The Tonight Show, and Zemeckis dishes them out accordingly, one bite apiece.

Through it all Forrest remains firmly lodged in our affections because, aside from his unwavering loyalty to his mother and his few friends — Jenny and two Vietnam buddies, Bubba (Mykelti Williamson) and Lieutenant Dan (Gary Sinise) — he literally doesn’t know what he’s doing. Whatever he becomes a part of — Vietnam, the antiwar movement, Watergate, new-age spiritualism, capitalist success — his sanctity is guaranteed by the fact that he knows how to follow orders, letting others determine his fate. Just like Oliver North, he’ll stand on his head if someone in authority tells him to. His lack of guile and volition (“Shit happens”) becomes our ultimate safeguard — he’s living proof that good-natured innocence will enable us to survive and even prevail as inert, uncritical spectators of the passing parade. Like Forrest we may lose most of our loved ones along the way, but after all we still have our TV sets.

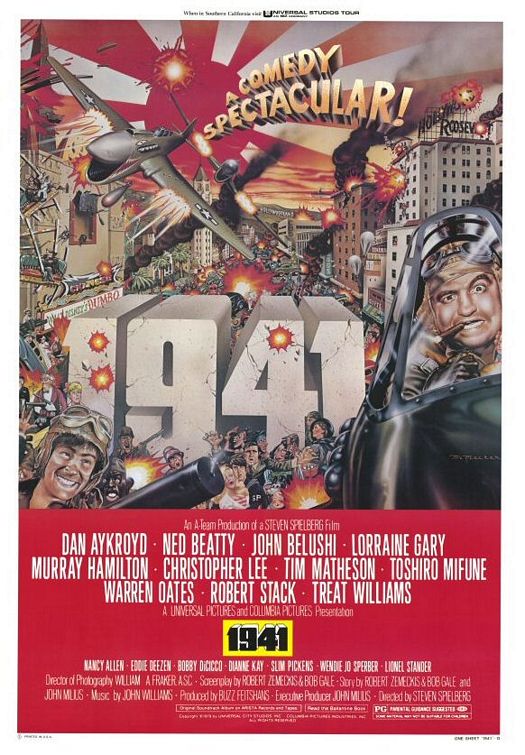

Not a director previously known for his humanism or sentimentality, Zemeckis seems to have his cultural roots firmly planted in the iconoclasm of Mad comics of the 50s. This spirited, anarchic nastiness can be detected in the script of 1941 (which he coauthored with Bob Gale and John Milius) as well as in the pictures he’s directed, including Used Cars, the Back to the Future trilogy, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, and Death Becomes Her. Zemeckis is a showman, adept at scrambling and reprocessing media stereotypes in the Mad manner, fully capable of wringing yocks out of wartime deaths (as in the Forrest Gump gags about Lieutenant Dan’s military ancestors croaking) as well as out of civilian mutilations (the hole blown through Goldie Hawn’s stomach in Death Becomes Her). In most of Forrest Gump, I hasten to add, death and mutilation are played for tears rather than laughs — though our awe at the technical stunt of making Sinise appear legless matches our awe at the hole in Hawn’s stomach, an awe that may actually supersede any other emotion.

It could be argued that Mad-style satire, which was a form of rebellion against the straitlaced repression of the 50s, has become an easy way for both entertainers and viewers to avoid political commitment of any kind. Some of this may apply to Forrest Gump, but the movie is nowhere near as politically uncommitted as it pretends to be. The style of humor may be indebted to the 50s, but the particular “insights” into the 50s, 60s, and early 70s belong almost exclusively to the late 70s, 80s, and 90s, and smack of the neocon jeering found these days in the pages of publications like the American Spectator, a view to which this movie seems very committed indeed.

Consider the evidence: Forrest Gump depicts Vietnam as a tragedy only for Americans (there’s not a single Vietnamese in sight), none of whom exactly “chose” to go: they simply found themselves miraculously transported there (see The Deer Hunter and Casualties of War), fighting for incomprehensible reasons. The antiwar movement was a cynical con game spearheaded by pushy women, ranting Black Panthers, and unwashed male hippies who liked to slap their flower-power girlfriends around, giving the lie to their “peace” platform; hallucinogens led straight to hard drugs; and so on. The mutilated veteran (Lieutenant Dan) is understood strictly in terms of other Hollywood movies — Midnight Cowboy in one gag, then Born on the 4th of July more generally — because no other reference points are considered viable. (Maybe that’s the reason for a clip from The Birth of a Nation — because only a famous movie can authenticate the Civil War.)

In the past I think I’ve overvalued Zemeckis for his craft and cunning (Who Framed Roger Rabbit) and perhaps undervalued him because of his brutality and misogyny (Death Becomes Her). I’ve focused here almost exclusively on what strikes me as appalling about Forrest Gump, but it does have its fair share of attractively composed shots, shimmering landscapes, finely tuned performances, tender moments, funny lines, and sincere emotions built around a touching love story (Forrest and Jenny) developed over several decades. What all these virtues are placed in the service of, however, is monstrous.

It often suits our vanity to say that the wind blows us this way and that way, that life is ineffably absurd and loaded with ironic twists: it’s a philosophical escape hatch, freeing us of all responsibility. But Forrest Gump is actually predicated less on arbitrary fate than on the pleasure of two forms of redemptive innocence. There’s the innocence of Forrest Gump toward American life and history: we’re asked to be charmed by yet feel superior to his fool’s progress. Then there’s the innocent nostalgia of our own more “sophisticated” (i.e., jaded) view of American life and history, which is assumed and imposed by the movie — a cornucopia of received media ideas, images, and artifacts — and which we’re not supposed to question. Eventually these two levels of innocence — which might be more rudely defined as two levels of stupidity — merge, so that by the film’s end Forrest Gump’s innocence is felt to be a higher form of wisdom: our own. It’s a classic American myth, the celebration of stupidity as redemption, and the “whims of fate” idea is little more than a smokescreen for the highly orchestrated marketing campaign that puts it across.