From the Fall 2019 issue of Cineaste. — J.R.

On Cinema

By Glauber Rocha, edited by Ismail Xavier. London/New York: I.B. Taurus, 2019, 306 pp., Hardcover: $110, Kindle: $85.

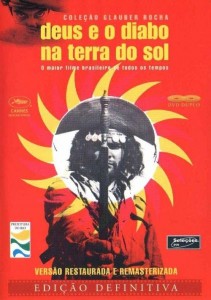

I’m strictly an amateur on the subject of Glauber Rocha (1939-1981), identified on the back cover of this pricey volume as “Brazil’s most important filmmaker and founder of the 1960s and ‘70s Cinema Novo movement”. But even a cursory glance at the limited availability of his films to Anglo-Americans without a grasp of Portuguese reveals that I have plenty of company, and this book offers us an invaluable starting-point for diminishing our ignorance. Eleven years in the making (and with ample confirmation that this painstaking care has paid off in terms of fluidity and clarity), with five individuals apart from Rocha listed on the title page — editor Xavier, general coordinator Lúcia Negib, Cecília Mello for final text and notes, and Stephanie Dennison and Charlotte Smith as translators — this is a rich assembly of articles drawn from three separate collections of Rocha’s writing: Critical Review of Brazilian Cinema (1963), The Cinema Novo Revolution (1981), and The Century of Cinema (1983), the first two of which were put together by Rocha himself. Xavier edited new editions of all these volumes that were published in São Paulo between 2003 and 2006, and has here selected representative extracts from each of them and contributed a new Introduction for us Yankee latecomers. (More detailed and particularly helpful accounts of Rocha’s early and major features can be found in Xavier’s 1997 book, Allegories of Underdevelopment: Aesthetics and Politics in Modern Brazilian Cinema.)

Given the difficulty of assimilating Rocha’s already-available films without many of the historical and cultural pointers that would make them more legible, this volume of theory and criticism is an essential guide, although we could also clearly benefit from the sort of detailed explications recently accorded to Aleksei German, another unruly avant-garde renegade who sorely needs deciphering for outsiders, in Arrow Academy’s superb recent Blu-Ray edition in the U.K. of Khrustalyov, My Car!—explications that move well beyond the skeletal history of Brazil delivered to children by the eponymous hero of Antonio das mortes in that film’s opening sequence. But in the meantime, the clarifications offered by On Cinema are already substantial, and the challenges offered by Rocha’s eccentric traits as a writer (like Ezra Pound, he often invented his own spellings), which parallel his often-contradictory approaches to filmmaking, are considerable.

To cite just a few of the obstacles posed by Rocha’s films to initiates like myself, there’s a demonic mix of religion, politics, mythology, and folklore, each of which can mutate into one or more of the others at the drop of a hat (and complicated by what Randal Johnson calls Rocha’s unorthodox “Protestantism”); a tendency towards delirium (“My madness is my conscience,” blurts a character in Terra em Transe) that includes a preoccupation with operatic violence (actual or potential) informing all of the above; and Rocha’s extended political exile (1969-1976), when he shot and/or edited films in the Congo, Spain, Italy, and Cuba, none of which are available in stateside editions. More directly accessible are an emotional intensity that remains fairly constant, a passion for the dispossessed, and a rethinking of cinema in terms of sound, silence, performance, music, choreography, camera movement, and landscape. What I miss most in his films is the sort of affectionate humor associated with primitivism that’s found in his Cinema Novo compatriot Nelson Pereira dos Santos. Similarly, even when Rocha’s prose turns playfully daffy, it rarely provokes laughter.

A self-styled auteurist critic, Rocha chose as his guiding light in poetic Brazilian cinema not, as I would have suspected, Mário Peixoto, the legendary auteur of Limite(1930), but the less known Humbero Mauro (1897-1983), whose most famous film, Ganga Bruta, can be accessed (albeit without English subtitles) on YouTube: “If [Limite]…visibly corresponded to a symptom of the French avant-garde and revealed an artist impregnated with subjective aestheticism, [Ganga Bruta] in 1933 not only corresponded to the poetic symptom of Vigo and Flaherty, but it was also associated with a reality that didn’t limit it with an intentional language.” For the founding events of Cinema Novo, Rocha selects Pereira dos Santos’ Vidas Secas (Barren Lives, 1964) and writes the following year his signal position paper, “An Aesthetics of Hunger”.

This essay begins with a blistering account of the colonial condescension with which Latin America in general and Brazil in particular is viewed by European esthetes, leading to “lies passing as truths” and “social problems conveyed through formal exoticism [his italics]”: “This economic and political conditioning has led us to philosophical disability and to impotence which, at times unconsciously and at times not, creates sterility in the former case and hysteria in the latter.” Rocha then proposes with fighting words a cinema that embraces rather than refutes or shrinks from hunger: “The Brazilian doesn’t eat, but he’s ashamed to say so. More importantly, he doesn’t know where his hunger comes from. We know — we who made these ugly, sad films, these screaming, desperate films, in which reason hasn’t always taken center stage — we know that hunger will not be cured by government plans and that the cloak of Technicolor will aggravate rather than hide the physical evidence of this disease. Thus, only a culture of hunger, weakening its very structures, can overcome it in qualitative terms: and the most noble cultural manifestation of hunger is violence.”

Perhaps the simplest routes into Rocha’s positions to be found in this section are his extended 1967 conversation with Michel Ciment in the French monthly Positif and his 1970 discussion in Italy with Bernardo Bertolucci, Miklós Jancsó, Jean-Marie Straub, and actor-filmmaker Pierre Clementi, titled “This is How the Revolution in Cinema is Made”.

None the less, Rocha’s critical pieces in The Century of Cinema about (among others) Antonioni, Buñuel, Chaplin, James Dean, Eisenstein, Fellini, Ford, Godard, Huston, Kubrick, Lean, Pasolini, Rossellini, Visconti, Welles, and Westerns may provide the surest path into his polemical and political positions. For the most part, his film criticism is lucid and perceptive, responsible both as journalism and as aesthetic and political analysis, especially when he’s dealing with such figures as Buñuel, Ford, early Kubrick (from Killer’s Kiss to Paths of Glory), Lean, and Rossellini and such subjects as juvenile delinquency. (On the latter topic, he’s especially good on the “choreographic realism” of The Wild One, Blackboard Jungle, and Rebel without a Cause, concluding that Nicholas Ray in Rebel, unlike Richard Brooks in Blackboard, “carried out poetically the intentions of Laszlo Benedik” in The Wild One.) Chaplin is someone he regards as “the revolutionary antithesis of Griffith,” viewing The Countess from Hong Kong as “the only film which Chaplin made from the point of view of the oppressor”. There are several pieces in defense of Godard that are reasonable enough yet by now stereotypically familiar, echoing many of the arguments heard around the globe during the 60s. On Eisenstein–another favorite and a clear role model–Rocha’s smart enough to see Ivan the Terrible as a critique of Stalin rather than as a mere capitulation to Stalin’s whims (as James Agee and Dwight Macdonald tended to assume). It’s mainly when he takes on Welles that he starts to sound not only idiosyncratic but a little bit loony. For starters, Welles is approached as the Western counterpart to Eisenstein: “If Eisenstein was the main interpreter of the Russian Revolution and of the radical transformations brought about by socialism, OW was the main interpreter of imperialist tragedy”. This is provocative and persuasive until one discovers that Rocha finds this theme in virtually all of Welles’ films, maintaining that he even “detests and destroys …buffoons like Falstaff”. This ultimately leads him to link The Trial with The Magnificent Ambersons, and, even more recklessly, with the Kennedy dynasty: “In Europe, [Welles] filmed Kafka, a metaphor for the true story of the Amberson Kennedy family”. In the same essay, where he spells “cinema” “kynema” (possibly in order to emphasize a connection of Welles to Eisenstein’s “kino”), he mixes metaphors further by positing that “the proletariat [in Citizen Kane] is the conscience of the narrator as interpreted by Joseph Cotton, Kane’s alter ego, the old and poor Rosebud in the happy retirement home.”

To my mind, there’s a clear relation between such head-scratchingly opaque poetic pronouncements and the crazy-quilt mixes and wild ambiguities of Black God, White Devil and Antonio das Mortes, accounting for what keeps me perpetually stuck in my amateur status regarding Rocha. It’s not a relation that inspires much critical confidence in either accepting or rejecting him unequivocally. In the final analysis, it may be his amateur status as well as our own that makes him both problematic and irreplaceable, a bit like Jean Cocteau, Jean Rouch, and Welles himself. –Jonathan Rosenbaum