Commissioned by MUBI Notebook and posted there on June 19, 2020. — J.R.

There’s a lot of confusion about what improvisation in movies consists of — when it is or isn’t used, and sometimes what it means when it is used. Those who think that the dialogue in Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind is improvised don’t realize that the screenplay by Welles and Oja Kodar with that dialogue was published years ago, long before the film’s posthumous completion. It’s worth adding, however, that the film’s mise-en-scène was improvised by Welles on a daily basis. Similarly, those misled by director Robert Altman’s dreamy pans and seemingly random zooms in The Long Goodbye into concluding that the actors must be inventing their own lines are ignoring the careful work done by screenwriter Leigh Brackett, not to mention Raymond Chandler.

Many of those who associate improvisation with John Cassavetes — ever since he brazenly concluded his first feature, Shadows, with the printed title, “The film you have just seen was an improvisation” — don’t seem to realize that, long after the actors did their initial improvs in Cassavetes’ Manhattan acting workshop, most of the lines were set and even written down before the cameras started rolling. And when it came to Cassavetes’ better known and subsequent features, such as Faces, Husbands, and A Woman Under the Influence, what was Improvised were the stage directions — the movements and placements of actors and cameras — not the plots or the dialogue that Cassavetes drafted. Furthermore, the editing sometimes changed the meaning of the lines that appeared to be spontaneous. In the original, prerelease version of Shadows, the contrite little speech by Benny (Ben Carruthers) to his two buddies about having learned his lesson, after all three have been beaten to a pulp in a pointless brawl, proves hollow once he continues to behave as aggressively as he did before. Yet when the same scene occurs near the end of the release version, we’re implicitly encouraged to think that Benny might actually mend his ways.

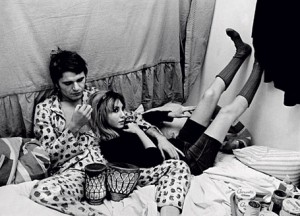

One can find many comparable contrasts in the two versions of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 – the 12-hour-and-40-minute Noli me tangere first screened in 1971 and the 4-hour-and-15-minute Spectre fashioned over the next year with a separate editor, both of them drawn from the same 30 hours of 16-millimeter footage shot during the spring of 1970. But the key difference between Rivette’s film in its two versions and those cited above by Welles, Altman, and Cassavetes is that all of the dialogue in Out 1 was (and is) improvised. So, for that matter, were the plot and the rudimentary mise-en-scène. The main role played by Rivette was to select the actors, inviting them to invent their own characters, and then, with the assistance of Suzanne Schiffmann, to arrange a series meetings between these characters—and, much later, to edit the results into two different films. Early on, it was established that two characters, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud and Juliet Berto, were eccentric outsiders and semi-comic solitary figures, and two others, played by Michel Lonsdale and Michèle Moretti, directed experimental theater groups preparing to stage tragedies by Aeschylus (although in both cases never advancing beyond various performing exercises). In this respect and others, Out 1was an extension of many principles underlying Rivette’s previous feature, the partially improvised L’amour fou, which costarred Jean-Pierre Kalfon as the director of a stage production of Racine’s Andromache and Bulle Ogier as his romantic partner, an actress who leaves the production and becomes a solitaire like Berto and Léaud in Out 1. The fact that Rivette himself tended to live like a solitaire when he wasn’t directing made the contrast between loneliness and collectivity in his work deeply felt and experienced. When Kalfon, in the midst of a quarrel with Ogier, began to slash his own clothes with a razor, leaving scars on his body afterwards, the effect was terrifying.

Léaud’s Colin, a mystic loner with a harmonica pretending to be a deaf mute, begs money out of café patrons; Berto’s Frédérique, another con artist, also works out of cafés, mainly by flirting with men. Both characters stumble upon information about an alleged secret alliance between several people, supposedly inspired by Balzac’s Histoire des treize, to control society, and Colin tries to uncover this conspiracy like a detective while Frédérique hopes to parlay a blackmail scheme out of it. Members of both theater groups and various friends—including a hippy boutique owner (Bulle Ogier), a novelist (Bernadette Lafont), and a lawyer (Françoise Fabien)—become implicated in the crisscrossing interactions, and there are also many cameos: Jean-Franois Stevenin plays a hood named Marlon who roughs up Frédérique; a bearded Eric Rohmer turns up as a Balzac scholar interrogated by Colin; and Stéphane Tchal Gadjieff, the film’s heroic producer (who has also produced films by Antonioni, Bresson, Duras, and Straub-Huillet), plays a messenger who inexplicably gets knocked unconscious by Ogier’s character with a wine bottle and then, just as inexplicably, is stashed in a trunk. If the latter detail evokes the silent crime serials of Louis Feuillade (Les vampires, Judex), which were often improvised as well, it’s worth noting that the poet John Asbury linked much of his enthusiasm for Out 1 around this similarity.

One of the aesthetic consequences of total improvisation is the implication that everything an actor does is theoretically interesting, especially once role-playing becomes the content as well as the form of any given sequence. From this viewpoint, fear of the camera, embarrassment, and other forms of what we normally term “bad acting” becoms as fascinating aa “good acting”, especially if the action oscillates between documentary and fiction. Jouer, the French word for acting, also means playing as well as performing, and this is a game played by those of us like Rivette who watch actors as well as by the actors themselves. The fact that Noli me tangere, unlike Spectre, is basically a comedy helps to foster the overall spirit of play. When Rivette edits the results differently in the shorter film, becoming a Fritz Lang rather than a Jean Renoir, the events take on a form of fatality or doom.

Rivette’s earlier role in influencing his actors’ inventions is difficult to pinpoint, but the subsequent testimonies of Berto and Léaud, among others, suggest that it was part of the game they were all playing. Léaud: “Jacques used a rather crazy side of my character that I hadn’t expressed yet. He said to me, ‘Carefully make your bed to perfection, then go to sleep on the floor.’ We developed a special bond working around the insanity of the character.” The major difference between the workprint version of Noli me tangere, which I saw in Rotterdam in 1989, and the finished version that we now have, is the deletion of a disturbing lengthy scene in the final episode showing Colin having a nervous breakdown. As far as I know, Rivette never spoke publicly about this deletion or its motivation, but I’ve come to suspect that his own identification with Colin must have played some part—suggesting that, as with Kalfon’s scene with the razor in L’amour fou, he must have felt afterwards that he’d gone “too far”.