Written for Cinema Guild’s Blu-Ray of Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, released in mid-January 2015. — J.R.

Stray Dogs (2013), winner of the Grand Jury Prize at the 70th Venice International Film Festival, is Tsai Ming-liang’s tenth theatrical feature. It was described by Tsai at its premiere as his last, and in many ways it’s his most challenging. Considered as the apotheosis of his film work to date — which also includes eleven telefilms made between 1989 and 1985, and ten shorts or segments of portmanteau features, culminating in the 2014, 56-minute Journey to the West – it constitutes a kind of nervy dare to the viewer, and to prime oneself for it, it might help to look at Journey to the West first.

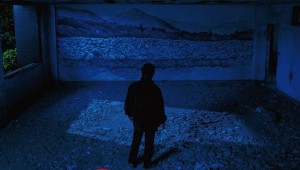

Even though both films flirt with stasis, usually in the midst of extremely long takes, they’re also performance pieces that hark back to Tsai’s roots in experimental theater and television. And the performers are not only hired actors but also unsuspecting street pedestrians, places, weather conditions, the camera, and, perhaps most crucial of all, viewers watching the activity of all of the above. If Tsai’s films typically qualify as questions rather than answers, foremost among the questions is how we perform as spectators – a question that we’re obliged to pose in relation to all the materials offered. It’s hardly coincidental that the longest take in Stray Dogs — the penultimate shot, almost 14 minutes long — is of two characters looking at something offscreen in an abandoned building (a landscape mural that Tsai found during his location scouting, already seen in the film an hour earlier, and viewed once more in the final shot) — a sequence that inevitably forces us to consider our own activity in watching these characters over the same length of time.

In Journey to the West, the materials are more clearly those of performance art staged on city streets – Lee Kang-sheng in a monk’s red robe inching forward at an almost imperceptibly slow pace, followed at some distance by an equally slow-paced (but more conventionally dressed) Denis Lavant — and the attentiveness or lack of attention paid by innocent bystanders (as well as the viewers of Journey to the West) to this spectacle is clearly part of the question being posed.

In Stray Dogs, where we have fictional characters -– a homeless, alcoholic, and fitfully employed father (again Lee Kang-sheng) with two small children (Lee Yi-cheng and Lee Yi-chieh), and a woman (played by three separate actresses -– Yang Kuei-mei in the opening scene, Lu Yi-ching at a supermarket, Chen Shiang-chyi in other scenes) who periodically takes care of the children –- but no chronologically continuous or coherent narrative, the questions that we’re asked to pose are far more numerous and various. Some of these have to do with our relation to the four characters, and others have to do with our relation to the film as a whole. Their lack of a stable home becomes the equivalent, for us, of our lack of a stable narrative, and this uncertainty persists during certain shots as well as between certain others. In the two most directly performative sequences — when Lee Kang-sheng recites and then sings a patriotic 12th century poem by Yue Fei while holding up a real-estate sign at a windy traffic intersection (the only job we ever see him have), and when he discovers on a bed a cabbage that his kids have decorated like a doll’s face before attacking, shredding, and devouring it in a paroxysmal frenzy -– the shifts in mood and emotional tone are particularly unsettling.

As a rule, continuity editing is maintained in Stray Dogs, but only within sequences and not between them, And the status of individual sequences in relation to what we regard as “real” or plausible or consistent with the others is chiefly a matter of how we choose to arrange them all to compose a coherent narrative of our own. When the woman character retrieves the children from their father disembarking in a rowboat in a driving rain, and this sequence is immediately followed by the woman and children presenting the father with a birthday cake in a dry, cozily lit interior, we’re obliged to ask not only what happens in between these two scenes –- assuming that they unfold in a chronological sequence -– but also how much either scene conforms to reality or fantasy in relation to these four characters (and if either scene qualifies as fantasy, whose fantasy it is). Elsewhere, we might ask ourselves, when we see the woman helping one of the children with what appears to be their homework, whether these kids are attending school. (The remainder of the film suggests that they aren’t.)

The problem isn’t, as one reviewer has suggested, distinguishing between “real” and “stylized,” because “realism” is a style in its own right, but how and where we situate ourselves within these conflicting scenes, styles, and modalities. In fact, we wind up shifting our perspectives as often as these characters shift their own living, working, eating, playing, cleaning, evacuating, and sleeping spaces, and the lack of any steady anchor conflates their brooding restlessness with ours.

If anything unites these sequences apart from people, places, weather, and the combined burden and privilege of watching, this is Tsai’s melancholy poetics and his mastery of sound and image. Characters cry in this universe, but as the woman remarks at one point, so do buildings, and the rain that falls on both is equally remorseless and relentless. And a key demonstration of Tsai’s mastery becomes apparent whenever one has an opportunity to watch one of his masterpieces with others in a crowded auditorium. I’ll never forget watching Goodbye, Dragon Inn (2003) on two separate occasions at Toronto and Chicago festival screenings, where the attentiveness of a packed audience facing an empty movie house was so hushed that one could hear a pin drop. Whether or not a home viewing of Stray Dogs can approximate such an experience is yet another question that this Blu-Ray of the film poses, but I would suggest that watching this film with others is a step in the right direction. Watching it alone might prove vexing at times; sharing its sense of gravity may help to illuminate some of its darkest corners.