Published under a pseudonym in the August 1985 issue of High Times. As I recall now, the main reason for the pseudonym was my unhappiness with the editor’s thoughtless editing; I’ve tried to repair a little of the damage here, and also added a few details.

I can happily report that Stapledon’s work has garnered a lot more attention since 1985, including a book-length study by Leslie Fiedler, and all the fiction discussed here is currently in print (or was when I last posted this), which wasn’t true back then. (Dover has excellent editions pairing Last and First Men with Star Maker and Odd John with Sirius, and An Olaf Stapledon Reader, edited by Robert Crossley, which Syracuse University Press published in 1997, includes all of The Flames and samplings from the others.) Although I don’t have much to say here about Odd John, this novel may actually serve as the best single introduction to Stapledon’s work. Although having just seen the late Jóhann Jóhannsson’s original and powerful experimental feature [see still below] loosely based on Last and First Men, released earlier this year [2020], I wonder if that might also serve the same function.

One anecdotal epilogue to Jorge Luis Borges’s interest in Star Maker, cited at the end of this piece: I was lucky enough to attend a public discussion with Borges at the University of California, Santa Barbara shortly before his death, and asked him at the time to comment on this book. He said that he hadn’t reread it since the 60s, “but of course, once you’ve read it, you can never forget it.” — J.R.

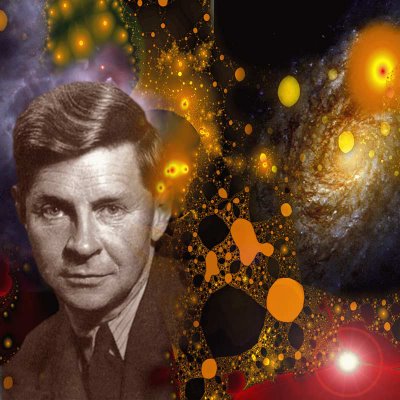

Without Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950), science fiction classics as diverse as Childhood’s End, Dune, the Foundation trilogy, Methusaleh’s Children, More Than Human, The Sirens of Titan, Solaris, and 2001: A Space Odyssey might never have existed. No one in the whole field of science fiction has worked on as broad a canvas — the remaining two billion years of mankind (Last and First Men), the birth and death of the cosmos (Star Maker) — or delved into such mystical, arcane matters as the psychology and aesthetics of stars in their dancing orbits, or plant men who function as vegetables by day and as animals by night.

More ambitious, far-reaching and mind-boggling than any other SF practitioner, this English philosophy teacher who died thirty-five years ago is still far from becoming a household name, either in the U.S. or England. But there are plenty of signs that an awakened interest in Olaf Stapledon is finally beginning to take hold. Two excellent book-length studies have appeared in this country over the past three years, and about ten years back, one English enthusiast, Harvey Satty, announced the formation of an Olaf Stapledon Society. One also finds the author’s name cropping up in unexpected places — from the [recent] remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (where Veronica Cartwright recommends Star Maker, Stapledon’s masterpiece, to a Bellicec Mud Bath customer as “must reading”) to Saul Bellow’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet (whose eponymous hero discusses and claims to have known Stapledon).

Over half a century ago, when Stapledon’s first novel was published in 1930 — a “history” of the remaining two billion years of mankind entitled Last and First Men — he certainly had more clout in the higher literary circles. Arnold Bennett, Winston Churchill, Alfred Kazin, J.B. Priestly, V.S. Pritchett, Hugh Walpole, and H.G. Wells all expressed admiration for this strange fruit from a late-blooming author, who was already well into his mid-forties when he started writing fiction. (“No other book had a greater influence on my life,” Arthur C. Clarke would say later; and Stapledon’s subsequent Star Maker would draw a fan letter from no less than Virginia Woolf.)

In its totality, Last and First Men tells a story, and a sadly elegaic one, about “this brief music that was man” — but it is a story in which whole eons of individual generations often take on the qualities of single characters. And the plot takes many unexpected turns: the Second Men, for example, emerge about 98,000 years in the future, after a global holocaust which reduces the world population to thirty-five people who happen to be around the North Pole at the time.

Stapledon followed up Last and First Men with an inferior sequel, Last Men in London (1932), in which the same Neptunian narrator takes up temporary mental residence in an individual in present-day England. Then came a more conventionally plotted science fiction novel on the superman theme, Odd John: A Story Between Jest and Earnest (1935), which remains possibly his best-known work. His greatest work, Star Maker (1937), came next — a book about the entire history and breadth of the cosmos, conceived on so grand a scale that the entire “action” of Last and First Men is incidentally summarized in less than a single paragraph, a passing detail in a monumental (and very beautiful) tapestry. (In the first of three “time scales” included as appendices, the beginning and end of Homo Sapiens covers only the tiniest of fractions.)

Even more difficult to synopsize than either of the Last Men books, Star Maker, described by Brian Aldiss as “the one great grey holy book of science fiction,” begins and ends with a conventional Englishman in a small town, retreating to a hillside in the midst of a marital crisis to contemplate the stars. There he experiences a vision which allows him to travel across the universe in a disembodied state, visiting first inhabited worlds in other solar systems whose spiritual evolutions parallel that of man. Gaining telepathic communication with representatives from these other planets, he joins a community of symbiotic spirits who travel across the universe learning about life on worlds more and more remote from their own. The gradual expansion of this “we” to include the consciousness of the entire cosmos — which eventually includes even the alien psychology of stars and their own interactions — ultimately brings this collective mind face to face with the Star Maker itself, and a climactic recognition of the nature of the creation of the cosmos…not to mention a whole series of other cosmoses which preceded and will follow this one.

Conceptualizing and visualizing this staggering immensity is no easy matter for the uninitiated reader; but Stapledon’s brilliance makes it lucid, imaginable, and anything but purely abstract. An agnostic throughout his life, he remains a rarity among writers by being a rational mystic with a sense of the concrete, a humanist visionary with a profound — and profoundly English — sense of the everyday. His mainly humdrum, unpretentious prose — which has partially served to prevent him from acquiring either the reputation of a modernist or the popularity of a yarn-spinner — is actually a crucial part of his equipment, and a central aspect of his strength. Without it, we would never believe in the splendor of his designs.

Following Star Maker, Stapledon published six more novels between 1942 and 1950, the year of his death, at least two of which — Sirius: A Fantasy of Love and Discord (1944) and The Flames: A Fantasy (1947) — deserve to be regarded as classics. The first of these is the most powerful of Stapledon’s “intimate” novels (Odd John is a close runner-up) and by all counts one of the strangest love stories ever written, chronicling the relationship with a dog who develops a human brain capacity and the girl (and, eventually, woman) who grows up with him. The latter, a novella, is a tale recounted from a madhouse by a narrator who believes he’s in telepathic communication with a sentient flame that can still remember the solar explosion that produced the planets.

Significantly, Stapledon didn’t even consider himself a science fiction writer. Although he admitted in a 1937 interview that he had read Verne, Wells, and Edgar Rice Burroughs, he added that he had come across his first s-f magazine only the previous year, and was anything but impressed. As the great Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges once noted, in an introduction to a 1965 Argentinian edition of Star Maker (Hacedor de estrellas, Buenos Aires: Ediciones Minotauro) that he included in a book series that he edited, Stapledon’s style “suggests that before writing he had read a great deal of philosophy and not many novels or poems.” Borges also drew attention to the honesty and paradoxical lack of hubris in a work as all-encompassing as Star Maker: “Stapledon doesn’t shore up inventions to distract or stupefy the reader; with an honest rigor, he pursues and retraces the complex and obscure vicissitudes of his coherent dream….From our contemporary vantage point, Star Maker is more than a prodigious novel, it is a possible and plausible representation of the plurality of worlds and their dramatic history.” In short, it is almost as if Stapledon were dutifully furnishing a mundane road map which allows the reader to trudge at leisure through infinity and eternity, seeing what there is to see.