Written in 2013 for a 2019 Taschen publication. — J.R.

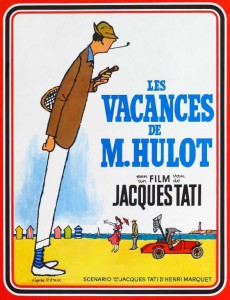

Mr. Hulot’s Holiday

1. Tati as traditionalist, Tati as experimenter

There’s a clear and consistent see-sawing pattern that can be traced over the course of Tati’s half-dozen features: a relatively conventional comedy with a relatively well-defined storyline is followed by something more radical, original, and experimental, and less bound or defined by traditional storytelling.

This isn’t only the way that PlayTime follows Mon Oncle and that Parade follows Trafic. The way that Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot follows Jour de fête is no less striking and significant. Even after we acknowledge that, as an original artist with an artisan’s sensibility, Tati invariably experimented in all his creative work — and that Jour de fête would have seemed more experimental in 1949 if he had been able to process and release it in color, as he had intended — one can still find a striking difference between his more narrative-bound and his less narrative-bound works.

At the same time, however, there’s a certain thematic continuity that’s followed from one feature to the next even when the style and form undergo important changes. On the most basic level, Tati’s first two films deal with vacation time and the second two deal with architecture. It’s harder to find any such clear link between Trafic and Parade — unless, perhaps, one postulates a similarity between automobile drivers and circus spectators (as Tati undoubtedly did). But there’s also a further dialectic between the overall terrains of these features, passing from (mainly) outdoors to (mainly) indoors.

Because it initially comes across as easy-going and laid back, as relaxed as an actual holiday, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday doesn’t strike everyone as an experimental film. But we overlook something if we assume that “experiment” invariably means trying out something new in order to see if it works. Sometimes it means expressing or doing something in a different way simply in order to express or do something that is otherwise inexpressible or unachievable. And in order for Tati to show what he wants to show, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday almost inadvertently revolutionizes what we mean by a feature film, as well as what we mean by film comedy.

2. Remembered Seaside Holidays

Tati grew up with many memories of seaside vacations with his sister Nathalie and his parents. One in particular which had a comic aspect that he liked to recount occurred when he was only eight. His father, Emmanuel Tatischeff — the son of a Russian Count who had grown up in luxury as a child, but had to scramble as soon as he became old enough to work — became apprentice to a prestigious Dutch picture framer named van Hoof whose customers included Toulouse-Lautrec and Vincent van Gogh, and he wound up marrying his boss’s daughter, Claire. His son Jacques’ favorite seaside memory was of his father joining him with his mother and sister when he was on leave from the French army in 1916, roughly halfway through World War I — but not in his swimming gear because regulations prevented him from removing his uniform unless he actually entered the water. For Tati at the time, it was a bit like trying to play in the sand with a bucket and spade under the prim and watchful eye of a village constable.

3. Who is Monsieur Hulot?

The title hero (or antihero) of Mr. Hulot’s Holiday is a character without a visible profession, a first name, or even, as far as we know, a family — the latter of which we learn about belatedly, and then only very partially, in Tati’s next feature, Mon Oncle. He seems to bring chaos with him wherever he goes, but it’s also clear that Tati approves of him in some fashion, because there’s something slightly sinister about the very notion of a “planned” vacation, and Hulot’s unwitting role in the film often appears to be disrupting people’s plans and bringing a certain impromptu spontaneity to the proceedings. He freshens things up, and not only because he tends to be cheerful and energetic, but at the same time it wouldn’t be quite accurate to say that Tati asks us to identify with him. The filmmaker bases much of his comedy on our capacity to be observant, and Hulot’s greatest failing is that he’s usually anything but observant; much of the comedy involving this character, in fact, derives from all the things he doesn’t notice. So perhaps it would be more accurate to say that if we identify partially with Hulot, what we identify with is his shyness, his awkwardness, and, above all, his cluelessness, which we’re also, paradoxically, alert and critical enough to notice.

During Tati’s stint in the army, he got to know a hairdresser named Lalouette who provided much of the original inspiration for Hulot (apart from his name, which he apparently borrowed from another conscript). Lalouette was a polite, unassuming, innocent, and essentially clueless fellow soldier who kept losing things and getting all of the military protocol wrong, such as calling all of the officers “sir” instead of addressing them by their specific rank (e.g., “mon colonel”), but who continued to look unruffled, with a complete lack of awareness that others found him funny. At once helpless and indestructible, Lalouette suggested a whole new approach to film comedy that would blossom into Hulot many years later.

Why does the village postman, François, in Jour de fête have a first name but not a last name, whereas Hulot has a last name but not a first name? Mainly, it would appear, because of class difference: working class types are likelier to be addressed by people who know them with a certain familiarity, but middle-class types, partly by virtue of their own shyness/repressiveness, are less likely to be comfortable with that form of address. Hulot, moreover, has some traits that make him seem vaguely English, which perhaps adds to the tendency of the other vacationers, mostly French, to address him with a certain polite formality.

Tati biographer David Bellos has suggested that many of Hulot’s most recognizable traits can be seen as inversions of those associated with Charlie Chaplin, who was literally English in his own origins: “a Homburg instead of a bowler, a blazer in place of tails, trousers too short in the leg instead of ones too long and wide, and in place of the cane, a variety of similarly stick-like but functionally different accessories — umbrella, fishing-rod, and butterfly-net.” But, as another biographer, Marc Dondey, has pointed out, the striped socks can be traced back to Buster Keaton in one of his early talkies, Parlor, Bedroom and Bath (1931).

Tati, who felt highly ambivalent about both Chaplin’s brand of comedy and his star politics, liked to compare his tramp character with Hulot in the following way: in The Gold Rush, when the Tramp is performing his famous “ballet” with two bread rolls fastened to the end of forks, we’re asked to admire the ingenuity, deftness, and grace of both Chaplin and his character. But when Hulot, through a series of mishaps (a flat tire; a damp ground which causes leaves to stick to his spare tire so that it resembles a funeral wreath; a misapprehension that he’s one of the mourners at a funeral, carrying this wreath), finds himself attending a funeral when he should be fixing his flat tire, it’s a set of interlocking circumstances rather the character’s cleverness or grace that creates the comic premise. Hulot, in short, could just as well be anyone else for this gag to transpire — and the notion that everyone could be funny, and not just a talented mime who dominated every shot and sequence, was central to Tati’s comic philosophy.

It might be argued, on the other hand, that the frequent claim that Tati’s humor is founded exclusively on observation, made by François Truffaut and others, seems contradicted by the brilliant funeral sequence, because it seems more than unlikely that Tati could have built such a gag out of something that he’d actually experienced or encountered in real life. On the other hand, one could also argue that, at least on a conceptual basis, Tati’s own creative ingenuity with pantomime and the spectator’s imagination is surely as much at play here as Chaplin’s was when he created and performed the dance with the bread rolls in The Gold Rush. The equation of comic concept with comic character is clearly not the same — even though there are key moments in Chaplin’s own comedies when mistaken visual impressions have complicated narrative consequences of their own (such as when the Tramp picks up a dropped flag carried by an activist in Modern Times and finds himself inadvertently heading a protest march, which lands him in jail).

4. Writing, Scouting, Casting, Shooting

For the screenplay of his second feature, Tati once again collaborated with Henri Marquet, with whom he’d written the script for Jour de fête, joined on this occasion by Pierre Aubert and his old friend Jacques Lagrange, and once again he preferred to carefully plot out as much as possible in advance rather than invent gags on the location. He was also very careful in selecting his main location: Saint-Marc-sur-Mer, located in Brittany on the western, Atlantic coast of France, between La Baule and Saint-Nazaire. It was a spot he arrived at with the help of the painter and designer Jacques Lagrange — someone Tati had known ever since he’d been working in his father’s picture-framing business, and who would subsequently collaborate with him as a designer and/or writer on all his subsequent pictures — who collected picture postcards from various seaside resorts. Shooting started in mid-July 1951 and continued, after extended breaks, the following summer, until October 1952, with interiors shot in the Boulogne-Billancourt Studios and exteriors short in Saint-Marc-sur-Mer.

Working this time with a heroine as well as a hero, Tati selected a friend of a friend named Jacqueline Schillio to play the important part of Martine; she agreed, although this proved to be her only screen acting role, even though she adopted a stage name for this particular role, Nathalie Pascaud. But because her husband, Jean-Pierre Zola, who owned factories in Lille, wasn’t very enthused about being separated from his wife during the length of the shoot, Tati offered to cast him as well, in a smaller part (not cited in the credits), playing a vacationing businessman rather like himself who keeps getting called away to the phone. (This is the character seen on the beach whom Hulot kicks in the rear when he sees him stooped down — actually taking a photograph of his family a few yards away, although Hulot assumes from his posture that he’s a peeping Tom spying on a lady in one of the bathhouses.) Years later, Tati would cast him again in a much more central part — and as another business executive, Charles Arpel — in Mon Oncle.

For other roles, Tati would depend largely on various Saint-Marc-sur-Mer locals (including a refreshment stand vendor who essentially plays himself, and a man with a white beard who plays an elderly relative of Martine), some of whom he also depended on for other services, such as boat rentals from the man who ran the local primary school with his wife, and who played a boatman in the film. He also drew on a few professionals, such as Raymond Carl to play the hotel’s head waiter, along with a few of his old acquaintances from the music-hall and elsewhere — such as Michèle Brabo, identified in the cast as a “summer visitor”, and a businessman he’d met in Lyon named Louis Perrault, playing a character known as Fred.

5. Tati’s Constructed Reality

The great French film critic André Bazin, one of Tati’s early champions, was especially insightful about his highly original use of sound in his second feature: “On a parfois dit à tort qu’elle était constituée par une sorte de magma sonore sur lequel surnageraient par moment de bribes de phrases, des mots précis et d’autant plus ridicules. C’est seulement l’impression qu’en peut tirer une oreille unattentive. En fait, rares sont les éléments sonores indistincts (comme les indications du haut-parleur de la gare, mais alors le gag est réaliste). Au contraire, toute l’astuce de Tati consiste à detruire le netteté par la netteté. Les dialogues ne sont point incompréhensibles mais insignifiants et leur insignificance est révélée par le précision même. Tati y parvient surtout en déformant les rapports d’intensité entre les plans sonores, allant même parfois jusqu’à conserver le sons d’un scène hors champs sur un même événement muet, Généralement son décor sonore est constitué d’éléments realistes: bouts de dialogues, cris, réflexions diverses, mais dont aucun n’est placé rigoureusement en situation dramatique. C’est en rapport à ce fond qu’un bruit intempestif prend un relief absolument faux.” (“It has sometimes been mistakenly said that the film’s soundtrack is made up of a kind of magma of sound on which snatches of sentences float, some of whose words are distinct while just as many others are nonsensical. This is nothing more than the impression of an inattentive ear. In fact, the film’s soundtrack is rarely indistinct, except for the loudspeakers on the train platform — but then this gag is realistic. On the contrary, all of Tati’s artfulness consists in destroying clarity with clarity. The dialogues are not at all incomprehensible; rather, they are insignificant, and their insignificance is revealed by this very clarity. Tati achieves this by deforming the intensity of the various levels of sound, sometimes going so far as to maintain the sound of an off-screen action over a scene shot silent. For the most part, his sound décor is made up of realistic elements: bits of conversations, cries, various kinds of remarks. None, however, is strictly located in a dramatic situation. In relation to this background noise, sudden noises take on an entirely false prominence.” Translated by Timothy Barnard in Bazin’s What is Cinema?, Montreal: Caboose, 2009.) Bazin went on to cite as an example of this the exaggerated off-screen sound of Monsieur Hulot playing ping-pong that disrupts the hotel guests’ more quiet activities in the evening.

One of the most telling phrases here is “sound décor”. We usually think of décor as something that is designed and built rather than as a “found” location, and the fact that Mr. Hulot’s Holiday was mainly (if not exclusively) shot on an actual seaside resort shouldn’t mislead one into thinking that it wasn’t partially designed and built as well. The façades of both the Hôtel de la Plage and the house where the character Martine stays were constructed sets, and the paradoxical reason for this was to make the film more “realistic”. The Hôtel de la Plage was a real hotel, and Tati insisted on shooting much of his film there while it went through its normal, everyday operations. But in order to do this without interfering too much with these operations, a fake front where he could shoot many scenes had to be built.

The subtle mix between real and artificial elements applied equally to the soundtrack, as Bazin was among the first to observe, and they even have bearing on our overall sense of some of the characters. Hulot, for instance, is defined for us, long before we even see him, by the loud sputtering of his old-fashioned car — to be precise, a 1924 Salmson AL3, modified for the shooting after being researched and sought by one of the film’s assistant directors, Pierre Aubert, and Tati’s multifaceted collaborator Jacques Lagrange. But it’s a safe bet that what we hear isn’t so much a documentary recording of the sound that emerges from a Salmson AL3 engine, modified or otherwise, as it is a constructed ingredient in the film’s universe, like a particular instrument in a composed piece of musique concrète, exaggerated to become grating as it hyperbolically rattles and wheezes.

Even if we assume that Tati started with the actual sound of a Salmson AL3 engine, the degree to which he’s increased its volume in relation to other aural elements is telling. If something that we hear is loud enough to irritate us, over time we may start to hear it subjectively as being louder than it actually is — as in the case of the buzzing wasp that chases after the village postman in Jour de fête, or the sound of a ping-pong ball being struck in this film. From this standpoint, Jean-Luc Godard’s witty remark in 1957 that, with Tati. “French neo-realism was born,” needs to be read with the understanding that expressionism in sound as well as image is sometimes needed in order to create a “neo-realistic” (or “realistic”) effect. Bazin’s example of the loudspeaker on the train platform is still another example of expressionistic sound used for the same purpose.

It’s also important to consider the way that sound and image complement one another in stimulating, directing, and inflecting our imaginations. Michel Chion, a French film analyst specializing in sound, has proposed an interesting experiment as a way of demonstrating how the ear leads the eye and vice versa: that we analyze the opening avant-garde and rather abstract sequence of Ingmar Bergman’s Persona with and without the sound, and a characteristically naturalistic and concrete sequence on the beach in Mr. Hulot’s Holiday with and without the image. In the first case, he observed that, without sound, not only does the first sequence of Persona lose its rhythms, its unity, and its meaning; it also looks different — a “shot” of a nail driven into a hand becomes three separate shots, and a narrative exposition of bodies in a morgue, without the sound of dripping water, becomes a disconnected series of stills without reference to either space or time. And in the second case, without the image of adults to “mislead” us, the apparent boredom, discomfort, and inertia of vacationers on a beach becomes the sound of lively children enjoying themselves.

6. Plot as Incident

Working without a plot in any usual sense, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday extends its story over one summer vacation period. Its incidents and sequences mainly consist of various mishaps engendered in one way or another by Hulot — including his arrival at the hotel (along with a gust of wind that disrupts the lobby), diverse misadventures on the beach, a vigorous tennis match with a couple of English ladies, a hired horse that turns out to be a mule, a shy and unsuccessful attempt to woo Martine (perhaps the most glamorous of his fellow vacationers), and a masked ball that ends abruptly with an accidental barrage of fireworks on the eve of his departure. But there are also some characters and incidents not including Hulot, such as the Colonel and his wife walking along the beach (she enthusing over various rocks and pebbles that she passes over to her husband, who tosses each one aside) and the carrying of two ice cream cones by one little boy to a pal of his in the hotel restaurant. More generally, there is a certain amount of boredom, a standard part of any holiday, which this film treats almost in musical terms.

7. Reception

Opening in late February 1953, Mr. Hulot’s Holiday proved an enormous success, making back near twice its production cost of 120,000 francs during its first release.

But, as with Jour de fête, this triumph only came after a lengthy period of discouraging bemusement and outright bafflement from many potential distributors. According to James Harding, one of these actually fell asleep during the opening credits and woke up again only during the climactic fireworks sequence.

And the film went on to acquire more awards and other honors than any other in Tati’s career, in France and elsewhere (including Belgium, Germany, Scotland, Algeria, Sweden, Cuba, and the U.S. , where it received an Academy Award nomination for the best original screenplay), making it his most famous film.

8. The Multiple Versions of Mr. Hulot’s Holiday

Tati removed Mr. Hulot’s Holiday from circulation in September 1959, envisioning first a virtual remake and then a substantial revision in terms of both editing and the soundtrack, and over eight years later, in late 1967, when this feature and most of Tati’s others went into escrow due to his bankruptcy, it was removed from circulation again. In between those date, in mid-February 1962, Tati released a second version, thirteen minutes shorter than the original release, with a recorchestrated and enlarged musical score to replace the one performed mainly by a solo piano in the original release. And a detail in color — a stamp and postmark — was added in a new final shot.

When this second version was rereleased in France, in late March 1977, it received 243,092 admissions in 29 theaters over 23 weeks. But meanwhile, after the 1975 release of Steven Spielberg’s Jaws, Tati had shot new footage on the Saint-Marc-sur-Mer beach to incorporate a reference to this movie at the end of his canoe gag. As biographer David Bellos describes it, “Tati had to have the kayak which folds in two when Hulot paddles it out to sea completely remade. He also had to assemble a large crowd of beach extras, wearing exactly the same costumes as those of the original film, and thus twenty-five years out of date. In the reshot sequence with the remade kyack, the inner lining of the craft tears into jagged shreds as a capsizing Hulot tries to free himself from the ‘jaws’ closing over him, and the shreds are so shaped as to resemble – rather vaguely – the teeth of a Great White Shark.” This elaborately revamped gag was cut into what Tati regarded as the definitive version of his film, completed in 1978.

9. The Carrying of Two Ice Cream Cones

Tati tended to prefer children to adults, both as spectators of his own gags and films and as purposeful, focused individuals who know what they want and how to set about implementing their desires, unlike many of their parents. A perfect embodiment of the principle is the very small toddler in Mr. Hulot’s Holiday who purchases two large ice cream cones from a vendor just outside the hotel. He’s introduced to us by just his right hand handing the vendor a franc note, and then, as the remainder of his body becomes visible, he precariously but gracefully proceeds to transport both cones, slowly climbing a stairway to join another little boy, a friend or relative, seated in a chair inside the hotel restaurant, where a waiter is putting up part of the décor for the upcoming masked ball. In order to carry out this seemingly mundane and simple task, he first has to slowly and carefully climb the formidable stairs, one step at a time, up to a door covered with a poster announcing the Bal Masqué, then reach the doorknob, which is well above his head, and successfully turn it, without dislodging the ice cream from the cone in his right hand — even though he has to twist the cone horizontally and then upside down in order to handle this manoeuver without dislodging the ice cream. Eventually he gets through the door, reaches the other boy, hands him one of the cones, and seats himself in the adjoining chair. They both proceed to eat their ice cream; mission accomplished.

This three-shot sequence occurs about 70 minutes into the original release version of Mr. Hulot’s Holiday, where its continuity after the first shot is briefly interrupted by a cutaway to a much older boy seated on a donkey while his mother fits him for right-size party hat (which is made to seem like a relatively silly and trivial activity). In the 1978 version, the scene occurs sooner, slightly over an hour into the film, and has an orchestral accompaniment. The earlier version has the advantage of a deliberately halting and tentative piano rendition of the same main theme, whose uncertainties mirror those of the toddler in his progress, while the re-edited version has the advantage of an unbroken continuity.

Most comic directors would regard this minor event as a recipe for disaster that achieves a payoff with some slapstick finale whereby one or both of the ice cream cones gets dropped or destroyed. Tati, on the contrary, invites us to gape in admiration along with himself at the determination, dexterity, and success with which this small task is successfully accomplished — and without any mishap, despite what might be regarded as a series of false alarms or at least attentive worries along the way. (The toddler himself begins his slow journey up the stairs by looking back and forth at the cone in each hand, as if to reassure himself that both are still there.) Insofar as Tati views much of everyday life as a serious of heroic or futile, routine or creative gestures, this is clearly a heroic undertaking, and one that even requires a certain amount of creative deliberation in order to be accomplished. Like a high-wire tightrope walker, the little boy needs to maintain perfect balance and equilibrium, and also to turn a doorknob without upsetting the cone held in the same hand. And Tati’s rendering of this impressive task has a genuine documentary integrity, even though it’s broken up into three separate shots, in contrast to the more typical moments in the film featuring outright gags. The structure of the “refused gag” noted by Noël Burch in PlayTime whereby comic potential — the mere possibility that a gag might occur — is everything, is already fully present here, in another form of what might be called Tati’s “constructed” reality.