Simon Petri-Lukács conducted the following online interview with me, about 5,000 words long, and requested that I post it here.(I’m sorry that many or most of Simon’s links as given no longer work, but many can be reached via my site’s search engine.) In fact, it’s an extended sequel to the in-person interview that he did with me in the lobby of my hotel in Budapest when I briefly visited that city in February 2022; the photo below shows us there and then, with a couple of friends. I’ll let Simon take over from here. — J.R.

I interviewed Jonathan Rosenbaum back in February when he visited Budapest. Then, I asked him to be the Jewish Museum’s special Skype-guest later this year and to have a discussion about Elaine May, following her first ever retrospective in Hungary. Because of the pandemic, of course, the retrospective had to be postponed. This interview covers, among other things, the topic of our cancelled Q&A. Furthermore, it offers a broader look at Jonathan’s favorite comedies and his opinions on Jewish stereotypes in American films. It also includes a discussion of his 1997 book, Movies as Politics and the role of literature in his life.

One thing I regretfully forgot last time was to recommend certain works of Jonathan which are available to everyone on this website – except for those periods when he circulates certain articles, but sooner or later they’ll all be there. It might be useful here in Eastern and Central Europe, where getting his books is often difficult.

Firstly, I’d like to highlight the original Movie Mutations correspondence. As most of the readers know, the main chapter consists of four letters, accompanied by Jonathan’s introduction and an extra response by Raymond Bellour. The four musketeers, sharing truly moving autobiographical details, offer an extremely intelligent, nuanced, and complex look at cinema and cinephilia. Their comments on larger, more general aspects of cultural life are also sharp and substantial, forming a rich, imaginary dialogue with Adorno. But before all that: the very origin of this correspondence exemplifies Jonathan’s generosity, sensitive attentiveness, and his absolute refusal to be interested in a correct, established wisdom – he connected people to make space for debate, contradictions and the beauty of various thoughts intertwining with one another: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2020/05/50734/

And some more:

Two texts, one about Oshima Nagisa, one about Ermanno Olmi, both about the complexity one can achieve by not surrendering to certain categories. In a film culture partly dominated by simplifying classification, so that in order to make everything fit one must overlook the truth, both should be widely read. 1) https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2019/03/the-sun-alsosets/ and 2) https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2017/06/problems-of-classification-a-few-traits-in-four-films-by-ermanno-olmi/

Two great catalogues: (1) A shorter text about Luc Moullet, one of the many filmmakers whom I discovered thanks to Jonathan. It’s the best introduction to his oeuvre I know and it briefly refers to Moullet’s politics and criticism as well. Plus (2), an exciting and diverse survey of films about the American South. The exploitation of Southerners in Hollywood films will come up in the interview, in relation to the topic of Jewish stereotypes. 1) https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2006/03/the-modest-master/ and 2) https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2020/02/visions-of-the-south/

Four of my favorite reviews from Jonathan’s prolific Chicago Reader period:

1) GREED: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/1999/11/fables-of-the-reconstruction-the-4-hour-greed/

2) LUMIÈRE D’ÉTÉ & LE CIEL EST À VOUS: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2018/08/bravery-in-hiding/

3) LE MÉPRIS: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2019/05/critical-distance/

4) DER TOD DES EMPEDOKLES https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2020/03/the-sound-of-german/

Unjustly, I guess, some of Jonathan’s “controversies” with other critics are more well-known than his passionate, warm writings on some of his colleagues. Here is one of the most important: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2019/07/raymond-durgnat/

Two exciting and refreshing comparisons of Elaine May and Erich von Stroheim: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2020/06/elaine-and-erich-two-peas-in-a-pod-tk/ & https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2020/01/21700/

Finally, an insightful and emotional homage to the great Samuel Fuller, one of the subjects of this interview: https://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2019/11/samuel-fuller-the-words-of-an-innocent-warrior/

THE CHISELER

SP: I’ve been thinking a lot about your interviews with Daniel Riccuito at https://chiseler.org. In the second one, you condemn the delusions and ignorance of 1960s radicalism. In the vastly different Hungarian context, I encounter similar criticism or self-criticism towards the blind enthusiasm of liberal (which here inevitably implies capitalist) intellectuals in 1989 – part of the matter being the inability to foresee the consequences for the factory workers, the unemployed, and the Roma community. At the same time, the outspoken expectation of many young leftists that members of the former democratic opposition of the Soviet system should denounce and despise their own joy and pride that they sincerely once experienced seems foolish and unsympathetic to me. It also lacks any serious desire for engagement with the complete history of 1989, the accomplishments, the shortcomings, the conversations. Do you ever feel that the distance between the environment, events or intellectual influences that formed your politics and the current trends, make it difficult for you to understand the latter? I am not implying that your influences are outdated, nor do I mean that current trends are necessarily unsatisfying intellectually. I am just curious if you share, to any degree, this generational isolation articulated by some in Central Europe – which, again, is mostly self-critical but also carries a sense of nostalgia for the Prague Spring, 1989 or in other cases for times when politicians – Willy Brandt, Bruno Kreisky, Olof Palme – kept a certain standard of civilized language.

JR: I’m far too much a 1960s radical myself to condemn that sensibility. If I criticize its naïveté or innocence about starting over again “from scratch”, this is only in order to defend the relative intelligence and practicality of many young radicals today who’ve learned to avoid some of my generation’s mistakes. This doesn’t mean that they don’t sometimes commit errors of their own — such as sharing Trump’s delusion that statues and names and televisual images are more important than laws. This over-reliance on symbols seems to me related to the error of defining the 9/11 assaults on the Twin Towers as “attacks on America [i.e., the U.S.]” rather than on the particular individuals who happened to be in those buildings — the idea over the reality, which for me is the fatal sin and error of PC thinking, even when it’s Trump who’s spouting it (or, in the case of those 9/11 postmortems, allowing the terrorists to define and categorize what they were doing rather than offering independent definitions). When both Trump and the activists privilege statues over people, it’s really an admission of political defeat.

To reply to the main thrust of your question, it seems that the calls for ideological purity in Eastern Europe point towards a similar lust, and one that needs to be countered with material facts and real (as opposed to ideal) memories and emotions.

SP: And a minor comment on the comparison of noir and “1930s leftism”. You refuse the notion that 1950s noirs are more realistic than 1930s films by socialists and say that “I think the popularity of noir today has a lot to do with a doom-laden death wish, a desire to escape any sense of responsibility for a future that seems helpfully hopeless (…)”. But don’t you think that this defeatism can also be understood as the acceptance of capitalist duties and responsibilities that come with them? I mean the basic motivation for Howard (Frank Lovejoy) in THE SOUND OF FURY/TRY AND GET ME! is to provide money for his family, to help them conform to capitalism. And in many Thirties films, particularly in comedies, that acceptance is either a surrender, a subversion of personal freedom, or it simply doesn’t happen and the main character, to cite the most obvious example, becomes a tramp. Attempts to break away from a capitalist way of living can be found in numerous 1950s Hollywood films, of course, but they are much hipper and much less poignant than those twenty years earlier. I wonder what you think about that.

JR: My comment about the current popularity of noir mostly relates to a certain defeatist attitude towards corruption that I see epitomized by the extravagant claims made nowadays for the GODFATHER films, especially THE GODFATHER, PART II. I tried to address this more specifically here: www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2019/06/14913/

SP: What does the defeatist attitude towards corruption mean to you? Sometimes I feel that corruption, economic corruption, is overrepresented in the critique of Trump, Orbán, et cetera, at the expense of a self-investigation of the opposition or the media, a consideration of how the feared and hated leader corrupts them and how they, without resistance or reflection, adapt their use of language to go along with the modes of hate speech. What I am trying to say is that I think governmental corruption is the main target of the media, which presented to the public as an objective matter by technocratic journalism, reinforces the idea that politics is pure techne and that it exists outside of the realm of mores.

JR:`You might well be right about this, but I have nothing to add to your analysis.

SP: Let’s talk about Elaine May. Since we wanted to do this for an audience that would see her works for the first time, it’d be great if you just talked about how you discovered her and how your relation to her four feature films developed since you’ve first seen them.

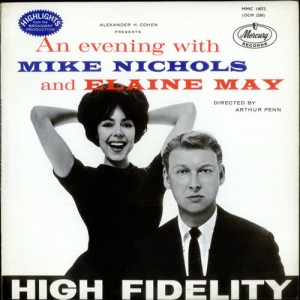

JR: My first encounter with Elaine May was on the 1960 comedy record album An Evening with Mike Nichols and Elaine May, tied to their long-running Broadway show. It had a galvanizing effect on me, and even then I was far more impressed with May than I was with Nichols — it was similar to my preference for Jerry Lewis over Dean Martin, because she was always the wilder and the more existentially committed of the two. I can’t remember now how or why I didn’t attend their Broadway show — I passed through New York many times during its run, and (for instance) saw no less than three plays directed by Elia Kazan during this period, and The Living Theater’s production of The Connection several times. I must have thought I would go eventually and then the show closed before I could. But the only time I ever saw Nichols and May live was very briefly, on the last legs of the Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama in the Spring of 1965, when they were part of a show on a muddy field in the black section of Montgomery.

If memory serves, I saw May’s second feature, THE HEARTBREAK KID (1972), before I saw her first, A NEW LEAF (1971), and this was in Paris. During the period when I was living in London, I managed to see MIKEY AND NICKY during a visit to New York in its rough-edit form, which is how Paramount chose to release it. (This was just before I met Nicholas Ray for dinner, the last time that I saw him socially.) Then I finally got to see its final version when I programmed it for a series called Buried Treasures at the Toronto Film Festival in 1981, not realizing that a differently edited version would be sent. And I saw ISHTAR (1987) during the final part of my sojourn in Santa Barbara, on a trip to Los Angeles.

I already thought of May being like Stroheim well before ISHTAR, but it may have only been with that film that I began to think about the common theme of betrayal that linked all four of her features.

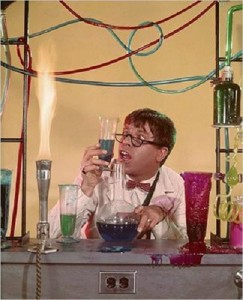

SP: In the comparison, you highlight that May’s films don’t feature total villains, one like Schani Eberle (Matthew Betz) in THE WEDDING MARCH. For me, her most frightening character is Lenny (Charles Grodin) in THE HEARTBREAK KID. Unlike the impostor Henry in A NEW LEAF or the tragic Mikey and Nicky, his nature is not transparently and evidently immoral. A salesman with a trendy car, he can be immediately and dangerously maddened by something such a man should have: the shiny, beautiful, sexy blonde. A man without qualities, to me, he is the only May character who is exclusively defined and wants to be defined by his marketable possessions. THE GRADUATE’s Mrs. Robinson is a sexist cliche but her character offers a quasi-legitimate base for Benjamin running amok. Among other things, what makes THE HEARTBREAK KID more challenging and braver is the opposite, non-apologetic concept: Lenny is the more powerful in the marriage anyway, which makes his actions way more cruel and agonizing. His fantasizing makes an obvious connection with THE NUTTY PROFESSOR too. You compare May’s performance in A NEW LEAF to Lewis’ physical comedy. What do you think about their respective autocritiques?

JR: The self-love crossed with self-hatred in Jerry Lewis is another version of what one finds in Welles, Kiarostami, Stroheim, and May, not to mention Albert Brooks and J.D. Salinger. They’re all writers-directors-performers whose autocritiques are often harsher than the critiques of others.

SP: JERRY & ME, a film by your friend, the brilliant Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa. is worthy of Lewis in its thorough introspection. It also offers a non-Western argument to demystify the “Lewis was only appreciated in France” theory. In what ways do you think her film contributes to a critique or understanding of Lewis, outside of a monocultural context?

JR: It’s both an embrace of subjectivity and an examination of what such subjectivity entails, which links it to Minnelli (another Pisces person, as I am) as well as Lewis. But Mehrnaz doesn’t idealize Lewis’ subjectivity, either, when she takes up his anti-Arab prejudices. It’s sad that Lewis became an enthusiastic Trump supporter before he died, but perhaps not too surprising, given his paranoia. I also have some trouble adjusting to the fact that Sam Fuller, a treasured friend, adored FORREST GUMP.

SP: I am very passionate about both of the May – von Stroheim texts I recommended above. Corrosive is a particularly powerful adjective for me to describe the similarities. As performers, both radiate a magnetic, paralyzing force and diabolic eroticism. Although in case of May’s portrayal of Henrietta in A NEW LEAF, it is rather anti-eroticism but the effect on Walter Matthau’s Henry is similar to that of von Stroheim’s intimidating aura. In regard to their differently harassed careers, do you ascribe any significance to the fact that May’s debut was recut by the studio whereas von Stroheim’s only “pure” film is BLIND HUSBANDS?

JR: I guess the main significance of this difference is that May had far less clout and power than Stroheim did, and some of this undoubtedly stemmed from the fact that she was both a woman and an outsider in Hollywood.

SP: What do you think Jewish baroque, a term you quote from Orson Welles, means? We are going to discuss Jewish stereotypes thematically and performance-wise, but is there a stereotype related to style? To whom can that be ascribed? Andrew Sarris famously noted that “Lubitsch was always the least Germanic of German directors, as Lang was the most Germanic.” What does that even mean? And where does Max Ophüls rank? Or von Stroheim or von Sternberg, if Austrians count too? Was there a tendency in American film criticism to generalize the – extremely stylish – Jewish filmmakers coming in from Austria or Germany?

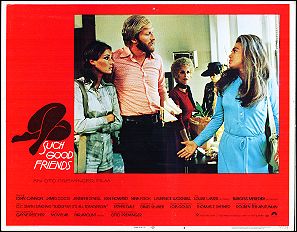

JR: I don’t think many American film critics were very conscious of the Jewishness or relative Jewishness of Lubitsch, Lang, Ophuls, Sternberg, or Stroheim. In the case of Stroheim, Welles figured out that Stroheim was Jewish while his friend was still alive, but others — including even Lotte Eisner, the German Jewish film historian, another friend — remained fooled by Stroheim’s impersonation. By “Jewish baroque” I think Welles was referring to a certain ostentatiousness, both as a showman and as a stylist, that reflected what he regarded as a Jewish form of extravagance. With Stroheim this became complicated by the fact that he was an imposter who played imposters — a show-off who was guilty of hiding in plain sight. And he pointedly removed the antisemitism of Frank Norris’ McTeague from his script for GREED in his treatment of the character Zerkow. Elaine May is of course far more open about the Jewishness of her own characters, at least in her last three features. Whether or not Jewishness is relevant in any way to A NEW LEAF can be debated, but it strikes me that the non-Jewishness of May’s Henrietta Lowell is firmly established by the character’s name. By contrast, “Esther Dale” — the pseudonym May chose for herself as screenwriter of Preminger’s SUCH GOOD FRIENDS — sounds Jewish to me.

SP: Maybe so, although I think Henrietta’s stumbling resembles that of Prof. Julius Kelp, which is a confrontation of (self-)stereotyping. In the interview, Daniel Riccuito mentions THE MAYOR OF HELL and you bring up one of my all-time favorites, HALLELUJAH, I’M A BUM. What do you think of Al Jolson in the film? Autobiographical details may not be so important but the fact that a Jewish immigrant plays this character adds a specific angle to the general leftist keynote. A fundamental doubting of the cliché that, unlike for other minorities, for Jews the American Dream has existed. Is there a stereotypical underclass Jewish character in the 1930s Hollywood films?

JR: Jewish stereotypes are more infrequent in Hollywood films than they are in films from continental Europe. In his brilliant video I, DALIO, Mark Rappaport persuasively shows how the Jewish stereotypes played by Marcel Dalio in prewar French films were replaced by French stereotypes when he emigrated to Hollywood, and Neal Gabler in An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood suggests that the creation of the American Dream by Jews had a lot to do with the denial of Jewish traits, stereotypical or otherwise — the literal theme of THE JAZZ SINGER. Jolson putting on blackface is one form of that denial, though identifying with Negroes (as they were called at the time) allowed him to deal with racial and ethnic difference and prejudice all the same. The bond between Jolson’s character and his black buddy in HALLELUJAH, I’M A BUM points to the same empathy.

SP: THE STRAWBERRY BLONDE is one of your favorites by Walsh. Do you have any particular interest in James Cagney?

JR: Cagney’s one of my favorite stars and actors, and the fact that he was Irish and could speak Yiddish suggests another case of empathy between minorities.

Sam Fuller was a friend of John Ford, and if I remember this correctly, Sam told me that Ford had both necklaces with the Christian cross and ones with the Jewish Star of David, which he’d wear according to whom he was seeing.

SP: You wanted to talk a bit about A SERIOUS MAN, a film you like. For me, it’s too deliberately fake and self-consciously smart. I don’t know how to put this in English but it’s somehow not imaginative enough to be surreal but too calibrated to resemble any genuine experience. One of the recommended texts above is partially about the exploitation of Southern stereotypes. Being a Southerner, what do you think of the Coens’ methods of portraying of the, let’s say M. Emmet Walsh type of characters? And don’t you see similarities in the way he portrays Jews? But of course, I’m open to learn about the values of the film!

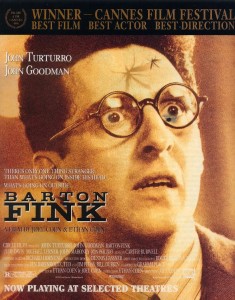

JR: Your explanation of what you dislike about A SERIOUS MAN strikes me as an excellent account of what I dislike about all of the Coen brothers’ films. My sneaking fondness for some aspects of A SERIOUS MAN in spite of this rests on its comic exploitation of a few Jewish stereotypes, which I suppose makes it a guilty pleasure of mine more than a virtue I can defend with a clear conscience, because it points to a reaction against obnoxious declarations of entitlement and moral superiority that I associate with some Jews as well as some manifestations of Zionism. By and large, the Coens use their Jewish stereotypes to discredit leftist positions in Hollywood, which I find detestable, just as I find their Busby Berkeley routine with the Ku Klux Klan in O BROTHER, WHERE ART THOU? disgusting rather than funny — the moral equivalent of cracking a tasteless joke about Dachau. So maybe the reason why I’m less offended by the antisemitic caricatures in A SERIOUS MAN is that they’re less tied to right-wing glibness than the Jewish stereotypes in BARON FINK and HAIL CAESAR! — although this assumption might be due to a certain naïvité on my part.

SP: I also think that A SERIOUS MAN is less offensive than BARTON FINK. As far as stereotypes are concerned, the non-Jewish characters bothered me actually, which is to say that the film presents them as hostile fascists or weak-headed cheaters. Which for me lessens the exploitation of Zionist behavior.

JR: What’s always objectionable and demagogic about the Coens are the ways that they doggedly flatter their audiences by granting them an unearned superiority over their dimwitted characters.

SP: The last comedy round: my favorite aspect of Luc Moullet’s singularity is the incredible intensity, seriousness and thoroughness of his examinations. In the title ESSAI D’OUVERTURE, essai means attempt I guess, but for a moment I always think that it means essay because it’s really an incredible study and he’s a great researcher! Which is also true for Tati. Would you like to talk about that and your discovery of Moullet’s criticism and films a bit?

JR: For me, Moullet’s greatness has a lot to do with what he can teach us about economy, in every sense of that word. His wit is the perfect alternative to the smart-alecky sense of unearned superiority that the Coens depend on for complicity.

SP: Reading has always played a pivotal role in your and your family’s life. In Movies as Politics, you refer to George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” as a touchstone throughout your career. I want to relate this to what you told me in February: “It’s partly the declaration of my last two books that I consider myself an artist at least as much as Manny Farber was an artist when he wrote criticism.” When you started to write criticism was it immediately evident to you to write it “just as stylishly” as a novel? Did you have merely stylistic influences, authors whose prose taught you something about criticism too?

JR: Farber was always a major influence in this respect, but so were Agee, Godard, and Bazin, in different ways, not to mention Dwight Macdonald, Susan Sontag, and the lesser known James Stoller. Andrew Sarris was a bad influence on me and many other critics when it came to using alliteration.

SP: What were the most influential novels for you as a teenager or young adult?

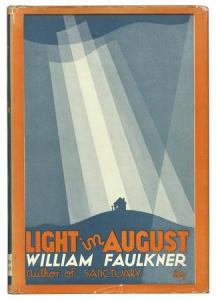

JR: Light in August and Dubliners were probably the two most seminal books for me in high school. Rabbit, Run and On the Road also had a considerable impact, and both of these built on my love for Huckleberry Finn. In college it was War and Peace and Remembrance of Things Past.

SP: What do you think of the overly frequent critical usage of the word novelistic? What does it tell about a film? You write for instance that “If BLIND HUSBANDS squats somewhere uncomfortably between a “symbolic” play and a cheap novella, FOOLISH WIVES all but invents the novelistic cinema.” Would you like to explain that?

JR: I associate the “novelistic” with the capacity to occupy, understand, and passionately emphasize with all the characters in a given story. For me, this is the genius of both FOOLISH WIVES and Light in August. (Some of the characters of FOOLISH WIVES can be seen, in costume, at the film’s premiere, in the second photo above.)

SP: The anti-cinephilic hierarchy of arts works on me! Even now, I often think “this film is as great as a novel.” I guess it means detailed and nuanced characters for me. Was there a period in your life, when the values you found in literature defined what you look for in films?

JR: Reading a novel commonly entails more creative collaboration than watching a feature because it takes more time and requires more concentrated energy and focus.

SP: Your book Movies as Politics was foundational for me. The concept movies as politics “entails looking not just at the political implications of many different kinds of films as “statements” and processes in themselves but also at the political aspects of what might be called the challenge of cinema — its aesthetic forms, its narrative tactics, and its patterns of production, promotion, distribution, exhibition, and reception.” I think it’s an incredibly valuable book today. Parallel to an increasing interest in activist films, documentaries about uprisings, et cetera, there is a worrying blindness to certain instances of antisocial attitude, class-hatred or simple reactionary lying in films that are not outrightly about history, politics, et cetera. An example of that would be the popularity of Ruben Östlund. Also, if the policy of a canon is to focus on films with a categorical social purpose, it reinforces this blindness to the fact that any work of art, regardless of its subject can be looked at that way. What do you think about that?

JR: I have so little interest in Ruben Östlund that I had to Google his name before I realized I’d seen a few of his films. The social uses of works of art obviously change over time, which is one of the reasons why canons can only be provisional, matched to particular historical moments.

SP: In our earlier interview, you made this comment about John Ford: “he was taken by many cinephiles in a right-wing way not in a left-wing way. I think he could be taken both ways.” For me, the grandeur with which he treats people’s trust in each other, their common sense, their willingness to cooperate for a shared good is always progressive. I think it’s very smart for example that Olaf Möller compares Ford to Frederick Wiseman. Would you want to go into detail about your remark?

JR: Don’t forget that the U.S. is largely a nation of flag-wavers more than a nation of thinkers. Jeffrey Hunter kicking his squaw bride down a hill (if I remember the moment correctly) in THE SEARCHERS for some low comedy kicks is not about people trusting one another, and neither are the spankings in DONOVAN’S REEF, clearly designed to gratify Ford’s anti-Bostonian impulses. And please don’t overlook the “politically correct lynching” that I’ve written about in THE SUN SHINES BRIGHT.

SP: Your Viennale text about THE SUN SHINES BRIGHT is extremely comprehensive and useful in exploring the film’s complexity. Many thanks for the reminder, I have to revisit both the film and your essay. DONOVAN’S REEF, which may not be a great film or one that I am fond of ideologically, sincerely and movingly refuses to be sardonic, even if its humor relies on simple-minded jokes. As far as the handling of Amelia’s eliteness is concerned, it’s partly a result of genre conventions, don’t you think? What I actually meant is that his understanding of communities is never regressive, never counter-Enlightenment. Exploitation of stupidity, evoking of envious and self-justified abuse of power is what he stands against, regardless of other, problematic matters. To name a few, I think of YOUNG MR.LINCOLN, MY DARLING CLEMENTINE, SHE WORE A YELLOW RIBBON, WAGON MASTER or SERGEANT RUTLEDG.. And admitting how conflicted and dangerous it can all be, as THE SEARCHERS does to a degree, is in itself progressive, to me.

JR: To me also. These are all great films, to be sure—even if some of my Alabama classmates may have been encouraged by SHE WORE A YELLOW RIBBON to fight in wars that they didn’t understand.

SP: Lubitsch comes up in your interview with Daniel Riccuito when you say that JEWEL ROBBERY is more radical about class and sex than TROUBLE IN PARADISE. Again, I must think of common sense and the dignity people handle their class- or sex-related conflicts in Lubitsch’s films. Looking at them today, in this political culture, this aspect strikes me as the most radical. I would be interested what you have to say about that.

JR: For me, William Powell and Kay Francis handle themselves, including their class and sexual conflicts, with a great deal of dignity, and I love the way that Powell pacifies the police with grass—a radical 60s gesture three decades before the 60s. Also, this may be only subjective, but I find Kay Francis both sexier and more sexualized in the Dieterle film, all the way up to her ecstatic and climactic closeup in the final shot. But I regard both comedies as masterpieces, and my main aim wasn’t to diminish TROUBLE IN PARADISE but to elevate JEWEL ROBBERY from its relative obscurity.

SP: Sorry for the imprecise question! What I actually meant is that out of all aspects of Lubitsch’s authorship, now, given the political culture discussed briefly above, dignity strikes me as the timeliest, not his more anarchic, extravagant and spectacular assets. In that regard, my favorites would be ANGEL and HEAVEN CAN WAIT. I didn’t want to put down JEWEL ROBBERY at all.

JR: My own favorite Lubitsch films would include THE MAN I KILLED, TROUBLE IN PARADISE, THE SHOP AROUND THE CORNER, and maybe DIE PUPPE and THE OYSTER PRINCESS among the silents.

SP: Vincente Minnelli, whose films are primarily concerned with the principles and conventions along which we live our social and family lives, isn’t often discussed as a political filmmaker. I am very curious to hear your thoughts about him.

JR: For me, Minnelli’s essence can be summed up in that beautiful line from Yeats, “In dreams begin responsibilities.” Which is another way of saying that he believes in both dreams and their good and bad consequences, and negotiating between the two invariably involves political judgments and decisions. Just for starters, consider the nightmare in FATHER OF THE BRIDE.

SP: It’s wonderful and so is the line you quoted. In the article I recommend about Samuel Fuller, you clarify some of the simplifying labels that were used to describe his films and ideology. Another misconception about him is individualism, which I think aims to explain his devotedness to autonomy without compromises. But his films are just as much about responsibility as they are about autonomy, don’t you think? I mean the relentless prioritizing of autonomy never allies with a separation from or an indifference to other people’s interests. What do you think about that?

JR: Sam Fuller’s movies aren’t only about crazed loners; they’re about interactions between mad individualists and nurturing communities.

SP: I would be thankful if you explained what you mean by nurturing! I guess I don’t get it but nurturing sounds odd regarding, let’s say RUN OF THE ARROW, UNDERWORLD U.S.A., or THE NAKED KISS.. With my dislike of the term individualist, whIch I overcomplicated above, I just want to say that the characters’ apparent solitude is rarely by choice, ideology, or selfishness. And what seems mad is sometimes the protection of what they regard to be sane in a maddened environment, no?

JR: It varies from film to film. But by “nurturing” I usually mean the supportive aspects of many of the women characters towards many of the male heroes, and maybe even the little boy in THE STEEL HELMET and other children in some of the films — characters who support the heroes in spite of everything. Of course the small town community in THE NAKED KISS is anything but nurturing, so I was guilty of over-generalizing.