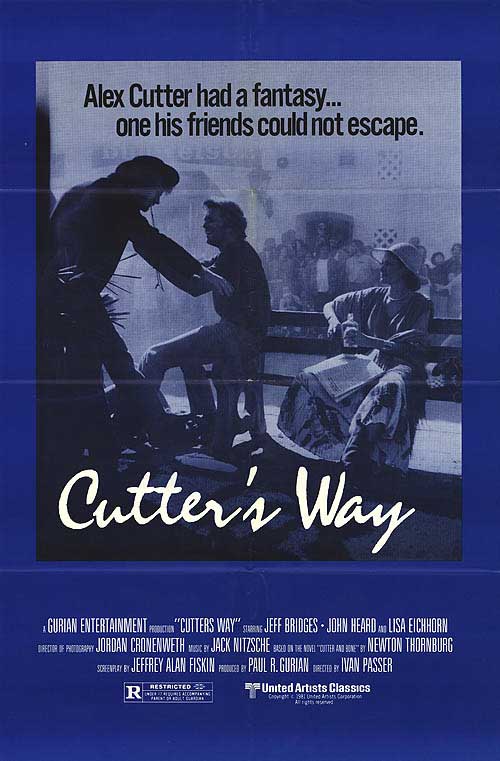

In celebration of Cutter’s Way, which Twilight Time brought out on Blu-Ray, and the wonderful Ivan Passer (1933-2020). This interview appeared in The Soho News, July 15, 1981, and was recently reprinted in my 2018 book Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues. — J.R.

A very likeable guy, this Ivan Passer. When he tells a story, he knows just how to pace it out dramatically, in filmic terms — a trait he shares with Samuel Fuller, who virtually stages movie sequences in the course odf describing them. A very different kind of director who also has a special feeling for outcasts, Passer pursues a subtle way of his own. A Czech in exile, he suavely took over my attention with the quiet intensity of a small, spry Ancient Mariner.

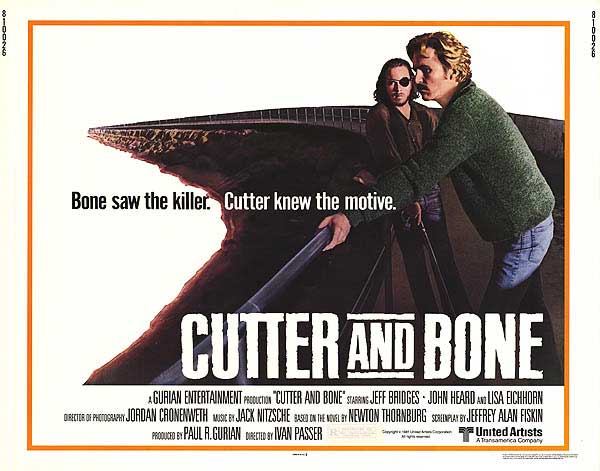

I had been knocked out by his passionate Cutter’s Way. Under the title Cutter and Bone, the movie had already been aptly praised in these pages by Seth Cagin and Veronica Geng — right around the same time that it was getting abruptly snatched from release — and it was a pleasure to find it living up to its notices.

It’s hard to be precise about the doleful yet personable wit projected by Passer — a matter of style, feeling and attitude more than taste or opinion –but it helps if you’ve seen one of his movies. Born in 1933, he started out as a scriptwriter for Milos Forman in Czechoslovakia, where he also made Intimate Lighting, his first feature, in 1966. His first American feature, Born to Win (1971), was my introduction to his work and its singular flavor — a warm, memorable movie about the “career” of a New York junkie, played by George Segal, who actually liked the hopeless sort of life that he led. After that came Law and Disorder (1974), Crime and Passion (1976), and Silver Bears (1978), then Cutter’s Way.

***

Jonathan Rosenbaum: Could you explain why Cutter and Bone was withdrawn last spring, and why it’s being rereleased now?

Ivan Passer: You know, statisticians say that there about eight things that have to happen at the same time in order to have a car accident. And all those eight things happened with my movie. It was jinxed because of Heaven’s Gate. People got fired, and the new people had no relationship with the movie. The ones who stayed there were afraid to have a relationship with the movie. So it was a hysterical atmosphere. We got a bad review in the New York Times — Vincent Canby panned it. And then, it’s not your traditional genre movie. So all those things together added up to what happened. They didn’t believe in it, they said, “We’re not going to throw good money after bad,” and they were ready to kill it.

JR: I know that Veronica Geng wrote a rave review of the film and was distressed to find that the film was no longer on anywhere when the review came out. And Seth Cagin had already reviewed the film very favorably.

IP: And the business after the first review picked up, doubled — that night. The theater manager called United Artists and said, “Please, I want to keep the movie, give me $800 for advertising.” but they said no. Can you imagine? So then it became a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy; they said, “it’s not going to do anything,” and they wanted to prove they were right. But then the critics rescued it — it was Soho News and the Village Voice. Those two reviews came out the same day. I thought it was over. I mean, I don’t get upset about things I cannot influence, so I thought, “Too bad.” But then Time came out, and Newsweek, and New York, and Soho News ran that second review, and it began to snowball. Then they sent it to the Houston Film Festival, where it won first prize. I thought François Truffaut’s The Last Metro would win it. And we got very good reviews there; the audience wrote cards that were 90 percent excellent. Then they showed it in Seattle where it got five stars, saying it was the best movie of the year, and other reviews said it was the best-looking film of the year. I’m amazed, really.

JR: Why has it been retitled?

IP: I don’t know, I hope they know what they are doing, because so far U.A. Classics has been doing a terrific job with this film, and it was their idea. It was United Artists who renamed my first American picture, Born to Win, which was originally called Scraping Bottom. It didn’t do any good, the renaming. You know, The Great Santini was renamed Aces. It’s sort of never worked before. Their reason was — and they might be right — because it was released as a murder mystery, which it isn’t, of course. And some critics said that Cutter and Bone sounded like it was about two surgeons. And they changed the whole campaign. They feel that people really shouldn’t go to see a murder mystery if it is not a murder mystery — they should know what they’re going to see. And they think the new name, Cutter’s Way, reflects better what the film is about. We’ll see.

JR: I’m very curious about the ending of the film, which I find very powerful. While working on the film, did you find it easy or difficult to imagine what would happen to Richard Bone, the Jeff Bridges character, immediately after the end?

IP: I think he gets away with it, because there are going to be fingerprints on the gun — the fingerprints of Cutter, because he’s still holding the gun when Bone pulls the trigger. There are no witnesses, and the fingerprints are definitely Cutter’s.

JR: I imagined something more apocalyptic. I thought about the ending of Born to Win — about how much you identify there with someone that society would call a loser. The whole movement of the film was toward Bone’s picking up that gun, and making that kind of commitment, and to end it that was very exciting. But it raised the question for me, is there any possible way he can get away with this?

IP: Actually, I shot what happens after that. He walks out of this huge mansion, and it’s just before sunset; and he goes faster and faster and finally begins to run through the trees. And there’s a scene on his sailboat, which he lives on. he’s sailing out of the harbor, and he hears a laugh that sounds like Cutter’s laugh. He stops and looks at where it came from, and he sees there are a few sailors on a small cutter. And one of them looks like Cutter; he’s drinking a beer. And he laughs again. At that moment, Bone almost hits the coast and the Coast Guard; he almost brushes against this huge boat. But he avoids the accident, and soon gets on the open sea, and sails away. They very much wanted this ending, but it took away something. You know, this film is about pulling a trigger — what it takes — and we felt, the writer, producer, and I, that this would be just a tag that would dissipate the emotional impact of that last shot, and so we pleaded with them, and they finally agreed.

JR: I’m glad they did. Is this a project that you initiated?

IP: No. The producer, Paul Gurian, bought the book written by Newton Thornburg, which is called Cutter and Bone. You know, we were thinking of changing the title in the process of making the film, but we were told that in the contract with the writer of the book there was a proviso that the film had to have the same title. And when Paul Gurian came to me, it was after Bob Mulligan had been working on it for awhile. He worked with the writer on the script, partly. Then it changed companies from EMI and it landed at United Artists when I came to it.

And you know, the way to get me interested in anything is to tell me it’s impossible to make. So that’s what I was told.

JR: Why was it felt to be impossible? Was it the nature of the characters?

IP: Yes, and it was a screenplay which sort of everybody read, and most people liked, and they were afraid of it. The companies, the majors, were afraid of it. They felt that it’s a downer — that the main character is going to be not very likable. And they also were suspicious about the genre, because they kept saying that the murder mystery plot isn’t very strong — which they were right about! They really wanted a murder mystery. Finally they said yes. Then they regretted it, I’m sure. And now they are glad.

JR: How would you say that most spectators respond to Cutter’s character, as played by John Heard? Are they repelled, sympathetic?

IP: Usually a combination of the two. I hope that, in the end, they’re completely on his side — that’s what I want. I don’t mind if they don’t like him at the beginning, which I think is the most common reaction.

JR: Why did you decide to eliminate Mo and Cutter’s kid from the novel?

IP: I think that was for purely practical reasons. It’s much easier to make a movie if you don’t have a small child, And we thought when the house burns down, with a child it would really be too much of a downer.

JR: Were there other substantial changes from the book?

IP: Well, there are some in the plot. But we tried very hard to keep the spirit of the original, which was very important. I was very happy to hear that Newton Thornburg likes the movie.

JR: Would you say it’s substantially the film you wanted to make?

IP: Oh, yes.

JR: Is that true of your other American films?

IP: Some of them.

JR: Which ones?

IP: You know, one of the unpleasant parts of being a director is you have to read scripts all the time, and 99 percent of it’s a waste of time. They are boring, bad. I get offered projects all the time. But it’s hard to come across a good one. I wanted to do Born to Win. And I wanted to do Law and Disorder. Then I wanted to do what I call my last Czech film, which is a story about an Italian baker in Brooklyn who has two sons who don’t want to be bakers. And nobody wanted to make that one.

— The Soho News, July 15, 1981