From Take One (January 1979). — J.R.

In order to do justice to the mesmerizing effectiveness of Halloween, a couple of mini-backgrounds need to be sketched: that of writer-director John Carpenter, and that of the Mainstream Simulated Snuff Movie — a popular puritanical genre that I’ll call thw MSSM for short.

(1) On the basis of his first two low-budget features, it was already apparent that the aptly-named Carpenter was one of the sharpest Hollywood craftsmen to have come along in ages — a nimble jack-of-all-trades who composed his own music, doubled as producer (Dark Star) and editor (Assault on Precinct 13), and served up his genre materials with an unmistakably personal verve. Both films deserve the status of sleepers; yet oddly enough, most North American critics appear to have slept through them, or else stayed away. Somehow, the word never got out, apart from grapevine bulletins along a few film-freak circuits.

Dark Star proved that Carpenter could be quirky and funny; Assault showed that he could be quirky, funnu, and suspenseful all at once. Halloween drops the comedy, substitutes horror, and keeps you glued to your seat with ruthless efficiency from the first frame to the last. A master of manipulating Hitchcockian point-of-view shots within a confined Hawksian community space. Carpenter is an advocate of straight-ahead storytelling strictly for its own sake. Aiming for a purified approach to genres, he uses only the minimal amount of topicality or psychology necessary to block out his his basic givens before charging ahead confidently, chewing up every inch of his carefully charted terrain.

In Halloween, this terrain is a quiet small town neighborhood where three teenage girls (Nancy Loomis, P.J. Soles and Jamie Lee Curtis) are pursued in turn by an escaped lunatic who murdered his teenage sister there 15 years ago at the age of six. Although titles situate this action in Illinois — perhaps in hommage to certain suspense stories by Ray Bradbury that utilize similar themes and atmospheres — the settin g is recognizably southern California.

Like the bargain-basement plot premise, none of this matters in the slightest. The neighborhood street and the interiors of two facing houses (where Curtis and Loomis are babysitting — plus another house nearly where the initial murder took place — are unobtrusively traversed so many times in the opening sequences by fluid camera movements that the setting becomes indelibly physical and familiar: beautiful, too, in the delicate bluish tones and Panavision framings of Dean Cunday’s photography. This gives Carpenter all the nails he needs to hammer us into his suspense mechanisms — helped along by his pounding piano-and-percussion theme — and play a subtle guessing-game with us as to whether the elliptically-glimpsed and masked psychopath is actually human or not.

It allows, too, for a loose, personal handling of actors that makes Donald Pleasence (as the lunatic’s doctor) unusually restrained, Nancy Loomis as delightfully Hawksian-angular-goofy-mannerist as she was in Assault, and Jamie Lee Curtis — daughter of Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis — an intriguing arsenal of shifting sculptural expressions and stances from one scene to the next.

(2) Curtis plays the part of the only surviving girl — significantly, the only virgin in the trio. Here’s where the MSSM comes in. A venerable genre that stretches all the way from Psycho and Peeping Tom to Klute and Looking for Mr. Goodbar to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Taxi Driver, it operates according to two fast and disgusting rules; suspense is generated by an audience waiting for a woman to be torn apart by a maniac, and the act is “morally” prepared for — unconsciously sanctioned — by identifying her with illicit sex.

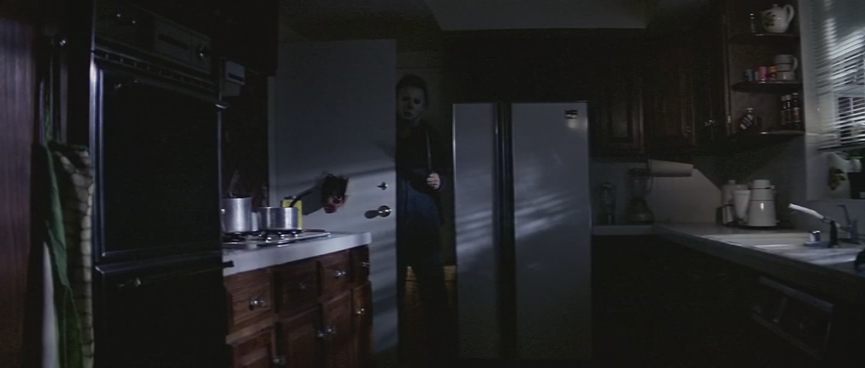

Halloween follows this ritualistic pattern with devoted rigor, so that the teenage victim in 1963 gets stabbed right after making love with her boyfriend (a view through a mask that we share with the killer); Loomis “gets hers” on her way to a sexual rendezvous (after an erotic ass shot), while Soles her her boyfriend are each murdered after a happy session in bed — the latter skewered to a kitchen wall and contemplated curiously by the psycho in a powerfully prolonged and silhouetted tableau.

There’s just as much a sense of loving, nostalgic design when Carpenter features clips from The Thing and Forbidden Planet on a Halloween TV horror show — both cunningly broadcast in their original ratios, which proves that he really honors what he plunders. The only question is, what is he (or are we) honoring in the MSSM, and what makes this morally superior to fondling Nazi war relics?

Jonathan Rosenbaum