From the Chicago Reader, February 25, 2000. This essay is also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

Rear Window

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Written by John Michael Hayes

With James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Thelma Ritter, Raymond Burr, Wendell Corey, Judith Evelyn, Ross Bagdasarian, Georgine Darcy, and Irene Winston.

Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest movie, Rear Window, is as fresh as it was when it came out, in part, paradoxically, because of how profoundly it belongs to its own period. It’s set in Greenwich Village during a sweltering summer of open windows, and it reeks of 1954. (A restored version, by Robert A. Harris, opens this week at the Music Box, and it’s so beautiful and precise it almost makes up for his botch of Hitchcock’s Vertigo a few years back.)

Peter Bogdanovich notes in Who the Devil Made It that Hitchcock “didn’t use a score” in the movie, “only source music and local sounds,” which isn’t exactly true. In fact, we get quite traditional theme music from Franz Waxman behind the opening credits, and, more important, the film subtly integrates hit tunes of the mid-50s into the ambient sound track, most noticeably “Mona Lisa” and “That’s Amore,” which was introduced the previous year by Dean Martin in another Paramount picture, The Caddy. The only serious flaw in Rear Window is the hokey use of a song to resolve a couple of subplots — which audiences in 1954 didn’t find convincing either.

When this romantic comedy-thriller was made, TV hadn’t yet posed a serious threat to radio, much less to movies, and there’s nary a TV set or TV screen in sight. The movie’s overall narrative form of scanning past windows in a courtyard seems to anticipate channel surfing, but it reflects the way one turns a radio knob, tuning in and out of frequencies while the station indicator moves horizontally or vertically along the dial. The same pattern is apparent in the beautifully calibrated camera movements as well as the brilliantly mixed and nuanced sound recording.

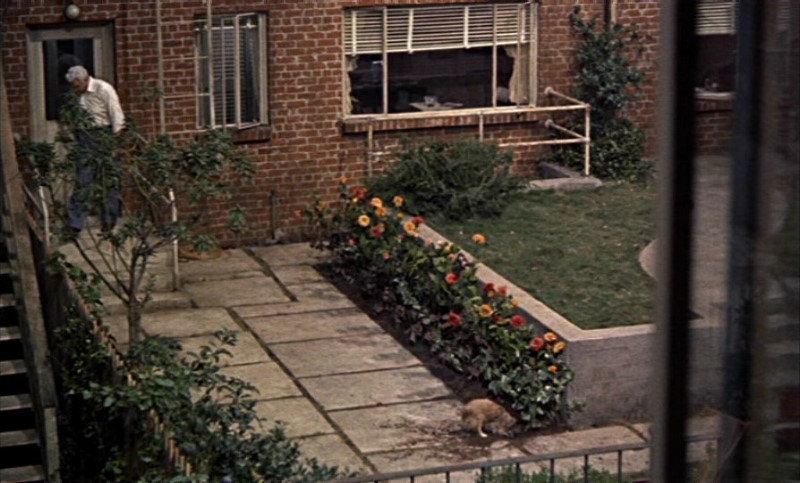

Turning a radio knob is actually the first decisive act by anyone in Rear Window. The camera briefly scans the courtyard that will remain the movie’s only location, showing the hero — L.B. Jefferies (James Stewart), better known as Jeff — fast asleep in the 92-degree morning heat. Then we see a composer (Ross Bagdasarian) across the way shaving, sufficiently irritated by a radio commercial (“Men, are you over 40? When you wake up in the morning, do you feel tired and run-down? Do you have that listless feeling?”) to switch stations to a rumba. The sound of an alarm clock shifts the focus to a middle-aged couple a few apartments away waking up on their fire escape, where they’ve bedded down to beat the heat. (In 1954 air conditioners were of course about as common as TV sets.) Then the camera dips down and to the left to show a curvy ballet dancer (Georgine Darcy) doing exercises while getting dressed — a musical-comedy heroine and va-va-voom 50s sex object, subsequently labeled “Miss Torso” by Jeff — before returning to Jeff and panning down to his left leg, which is in a plaster cast. It then crosses the room to show us succinctly who he is and how he broke his leg: we see a broken camera in front of a photograph of a racing-car accident, followed by other framed news photos, a negative close-up of a female model, and stacks of the Life-like magazine Jeff works for, with a positive image of the model’s photo on the cover.

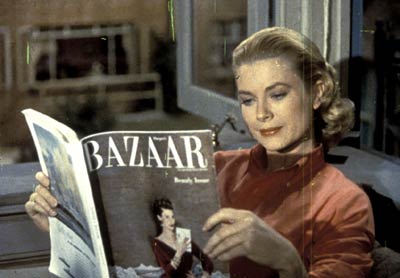

This introduction to Jeff reminds us of Hitchcock’s roots in silent cinema, but the highly developed sense of being current never falters. Some of this impression undoubtedly comes from the bantering dialogue of screenwriter John Michael Hayes, adapting a Cornell Woolrich story about an invalid so that it features more glamorous characters; Jeff’s girlfriend, Lisa (Grace Kelly), a chic, wealthy fashion buyer and former model, was apparently based in part on Hayes’s own fashion-model wife. Hayes was a radio writer with a flair for romantic comedy, at least in his first three scripts for Hitchcock — Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, and the underrated and uncharacteristically utopian The Trouble With Harry — and he had a light touch that was never matched by Hitchcock’s subsequent screenwriters, with the exception of Ernest Lehman, who scripted North by Northwest and Family Plot. The high-gloss sophistication and wit extends to the treatment of sex in the movie, which is a lot more daring than most other Hollywood films of the period. When Lisa announces to Jeff that she’s staying overnight and then proceeds to model her tiny overnight bag and the negligee inside it — both items occasion a few uneasy leers from Jeff’s detective chum Tom (Wendell Corey) — one suspects the censors were placated only because Jeff’s plaster cast made sex between him and Lisa seem unlikely. It’s interesting that Hayes’s original script intimated that Lisa was somewhat frigid and that Jeff was frustrated about not having had sex with her — two hints Hitchcock presumably got Hayes to eliminate. (This production information, and much that follows, is drawn from Bill Krohn’s indispensable Hitchcock at Work, which is based on diverse production records and scheduled for publication by Phaidon in the near future.)

Another, less obvious aspect of the movie that feels very up-to-the-minute is the way it evokes the Sunday funnies. Apart from movies and radio, comic strips were probably the most popular vehicle for narrative at the time, and the movie’s repeated traversals of courtyard windows capture some of the experience of reading one of those strips — especially when the windows frame one neighbor, traveling salesman Lars Thorwald (Raymond Burr), as he moves from hallway to kitchen to living room to bedroom, a journey comprising roughly the same number of squares as a daily strip. As Jeff becomes increasingly intrigued by the movements of the harried Thorwald and his nagging, bedridden wife (Irene Winston) — especially after she mysteriously disappears and Jeff suspects a murder plot — he finds himself “reading” Thorwald in precisely this manner, and the viewer is increasingly encouraged to “read” Thorwald over Jeff’s shoulder.

It’s impossible to know whether Hitchcock had comic strips consciously in mind, but Krohn told me he’s encountered intriguing evidence that Hitchcock encouraged Raymond Chandler, his screenwriter for Strangers on a Train, and the film’s production designer to study Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates while working on the film. Coincidentally or not, Frank Tashlin’s dazzling comedy about comic books, Artists and Models, was made at the same studio the following year and features a gag that’s explicitly about Rear Window. Fritz Lang read comic strips in the 30s to teach himself English, and Alain Resnais — surely the most Hitchcockian of all French directors — has said that most of what he knew about editing came from comics. (We do know that Hitchcock, in a private and intricate form of revenge, closely modeled Thorwald’s appearance after that of David O. Selznick, the control-freak producer who meddled in many of Hitchcock’s early Hollywood features. Five years later Hitchcock took another dig at Selznick in North by Northwest by giving his hero the same middle initial, which the character says stands “for nothing.”)

What do Hitchcock’s comic strips add up to? All the little stories about the people around the courtyard — who also include a honeymoon couple with a sexually insatiable wife who keeps calling her husband back to bed, a recurring gag few other Hollywood directors could have got away with in 1954; an avant-garde woman sculptor; and a love-starved single woman dubbed Miss Lonely Hearts (Judith Evelyn) — are variations on a theme concerning what it means to be part of a couple or to live alone, both situations being viewed darkly. It was an ideological staple of the Eisenhower 50s that family was everything and going it alone signified some form of quiet desperation and failure. Here, even the childless couple who sleep on the fire escape are perceived to be unhealthy because of their highly emotional attachment to their dog, and the lone, unattractive sculptor is seen working on a genderless figure with a gaping hole in its belly, a piece she calls “Hunger.” Hayes’s original script also had an adulterous love triangle involving two of the flats, which was replaced by the childless couple.

Two of the most poetic evocations of Greenwich Village to be found in movies, those in The Seventh Victim (1943, see below) and Rear Window, were shot in Hollywood studios, and both are models of cozy proximity and narrative economy, featuring lairlike garrets and densely populated neighborhoods filled with mysterious artists of various sorts. The Seventh Victim — the fourth and in some ways the best of all the horror quickies produced by Val Lewton, despite the convulsive beauty and dreamlike fluidity of the three Jacques Tourneur features preceding it — was shot largely on refashioned RKO sets built for The Magnificent Ambersons to create a claustrophobic vision of a nocturnal, bohemian Manhattan.

Rear Window, with considerably more money at its disposal, had a $100,000 set built — 38 feet wide, 185 feet long, and 40 feet high — combining Jeff’s living room, the only part of his flat we ever see, with the courtyard it overlooks. The set also included a short patch of sidewalk and street between two buildings and beyond that a bar, visible only when Jeff uses his telephoto lens to follow Miss Lonely Hearts when she leaves her flat. The fact that these buildings are supposed to be in the West Village may strike some viewers as beside the point, but to me it’s central: Lisa’s uptown and East Side trappings seem designed to contrast with Jeff’s humble abode and carefree manner, and when, late in the film, Thorwald is sent on a wild-goose chase so that Lisa can search his flat for evidence, Jeff arranges a bogus meeting with him at the Albert Hotel, a Village landmark — which suddenly makes it clear that the whole story has been set in a very distinctive location.

Simulating daylight on the monolithic set reportedly required practically every piece of lighting equipment on the Paramount lot. The set contained 31 apartments, a dozen of them fully furnished, and those in Thorwald’s building even had running water and electricity. Hitchcock gave some attention to color coding the background walls and costumes in these flats so that viewers could easily distinguish between them.

One reason Hitchcock loved working with such technical restrictions is that they forced him to use his ingenuity. In an impressive oeuvre, Rear Window is arguably the most exquisitely handcrafted feature, because Hitchcock mastered the spatial as well as behavioral coordinates of his chosen universe inch by inch. He can’t juggle foreground and background the way Tati could a decade later by using deep focus in Playtime, but it seems at times that he’s on the edge of some of the same perceptual possibilities — drafting the rudiments of a cinema of long shots that invites viewers to choose among the sights and events competing for their attention.

Rear Window has often been described as Hitchcock’s testament because it sums up so many of his ideas about filmmaking: his fascination with voyeurism, his love of technical restrictions (which had also motivated Lifeboat and Rope), and his cultivation of certain stars — it was the second time he’d used Stewart (Rope) and Kelly (Dial M for Murder). It also sums up his ideas about editing, especially as a means for soliciting the audience’s involvement in the action.

According to the famous “Kuleshov experiment” in silent Russian cinema, the same close-up of actor Ivan Mozhukhin seen by separate audiences with a bowl of soup, or a coffin, or a little girl automatically conjured up a hungry man, or a mourner, or a pervert. As Hitchcock was fond of pointing out, the same principle is at work whenever the camera cuts from Stewart to the neighbor he’s gazing at. Krohn reports that to give himself more creative leeway in editing — if not to create backup footage to mollify the censors — Hitchcock did many alternate versions of scenes and shots. (Perhaps the funniest of these involved the running gag of the honeymoon couple: Krohn writes, “Looking out at Jeff and Lisa, the groom is summoned once again by his wife and tells her to ‘start without me’ — a shocking suggestion that is explained when the shade goes up and we see that they have been playing chess the whole time.”)

Perhaps because he’s a risk-taking news photographer — a conventional adventure hero, at least by reputation — Jeff can pursue his somewhat morbid interest in Thorwald as a way of combating boredom while sitting all day in a wheelchair and remain the movie’s hero. But this doesn’t mean the movie lets him off without a reprimand. For one thing, Lisa has marriage on her mind, and Jeff is determined not to marry her. In a way, the story of Thorwald’s married life becomes a dark, speculative glimpse into the life Jeff is fearfully contemplating; it’s also an inversion of his own setup, with the woman playing the part of the invalid instead of the man.

Stella (Thelma Ritter), a plain-talking insurance-company nurse who turns up every day to give Jeff massages and take his temperature, serves as the voice of his reprimand for being a nosy snoop and the closest thing to a moral conscience in the movie. “We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms,” she says early on when she catches Jeff leering at Miss Torso. “What people oughta do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.” Yet as the evidence against Thorwald mounts, she gradually gets sucked in, spurred only by her curiosity and an abstract desire for justice. In this respect she becomes the spectator’s surrogate, an index of our own fluctuating moral relationship to the events occurring across the courtyard. (This may be Ritter’s best performance, though it wasn’t one of the six supporting roles for which she was nominated for an Oscar; the only other true contender is her police informant in Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street, which was nominated.)

Jeff is the principal voyeur in Rear Window, but Hitchcock takes care to show us Lisa’s and Stella’s responses as well, which aren’t always the same as Jeff’s. Lisa, for instance, responds more than he does to the composer’s music, and each of them is intrigued at different junctures by the plight of Miss Lonely Hearts, who’s clearly tempted by suicide, though each subsequently loses interest in her. That they’re more concerned about being amateur sleuths and capturing a murderer than in saving someone’s life is disturbing, and members of the audience are also indicted if they buy into the same narrative priorities.

Though neither an existentialist nor a Brechtian, Hitchcock remains a moralist, particularly when it comes to the questions raised by these characters’ interests in their neighbors and by the transfer of guilt from one character to another — an essential Hitchcock theme discovered by French critics such as Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol in the 50s. Another essential theme is the degree to which morality is a matter of experiencing life in long shot or in close-up. Thorwald is a grim monster in long shot, the only way we see him for most of the film, but he’s quite different when he’s standing across the room from us — reminding us of Charlie Chaplin’s observation that comedy is life in long shot and tragedy is life in close-up. The suspense in this movie is most potent when it hovers over such moral issues, as when Lisa takes risks on Jeff’s behalf and he’s powerless to stop her; the love story and the mystery plot are interrelated most complexly when she breaks into Thorwald’s flat to retrieve his wife’s wedding ring as a crucial piece of evidence, places it on her own finger when the police arrive, and then signals to Jeff from across the courtyard that she has it.

More than anything, Rear Window, without ever ceasing to be a grand entertainment, is a moral investigation into what we do and what that implies whenever we follow a murder plot as armchair analysts. Hitchcock explores the question from just about every possible angle, including the issue of whether we ogle our neighbors the way we ogle characters in plays and movies — from a dark place and a safe distance. The movie begins and ends with a theatrical metaphor — the raising and lowering of the window shades in Jeff’s flat as if they were stage curtains, a symmetry that was brutally violated in Universal’s previous rerelease version, which ends instead with the Universal logo.

Significantly, both the raising and the lowering of Jeff’s shades are fantasy images of divine intervention. He’s asleep during both events, and he’s alone in his flat when the shades are pulled up; when they’re lowered Lisa is nearby, but she’s sneaking a look at Harper’s Bazaar, not pulling the shade cords. The shades go up and down one at a time, without human intervention, and it’s clearly Hitchcock himself, more deity than director, who’s inviting us into his world and then ushering us out.