From the Chicago Reader (October 21, 1994). This is also reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

*** ED WOOD

(A must-see)

Directed by Tim Burton

Written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski

With Johnny Depp, Martin Landau, Sarah Jessica Parker, Patricia Arquette, Jeffrey Jones, Bill Murray, Lisa Marie, George “The Animal” Steele, and Vincent D’Onofrio.

*** PULP FICTION

(A must-see)

Directed and written by Quentin Tarantino

With John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson, Uma Thurman, Bruce Willis, Ving Rhames, Maria de Medeiros, Tim Roth, Amanda Plummer, Harvey Keitel, Eric Stoltz, Rosanna Arquette, Christopher Walken, and Tarantino.

[The media] ask those who know nothing to represent the ignorance of the public and, in so doing, to legitimize it.

— Serge Daney, Sight and Sound

If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story. — Orson Welles

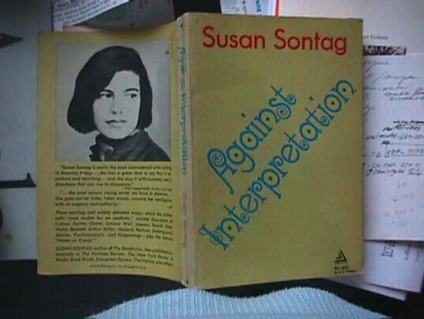

In Vamps & Tramps, Camille Paglia’s latest collection of sound bites and press clips, one finds an extended account of her long-term obsession with Susan Sontag, including the following nugget: “She is literally being passed by a younger rival, and she’s not handling it, I’m afraid, very gracefully. . . . I am the Sontag of the 90s, there’s no doubt of it.” Her statements recall Wynton Marsalis’s compulsive self-positioning as Miles Davis’s rival/replacement — especially in the 80s, when Davis was still alive — as well as repeated assertions reviewers have made over the past several weeks that Quentin Tarantino is Jean-Luc Godard’s successor. All three comparisons belittle the talent, intelligence, and historical roles of Sontag, Davis, and Godard, but it’s become increasingly apparent in our postmodern age that the logic of such comparisons has little to do with the original artists’ accomplishments. They’re about something else — an assertion of market value in a market defined by preexisting molds.

When Sontag wrote Against Interpretation, Davis recorded Kind of Blue, and Godard made Breathless, in the late 50s and early 60s, thereby expanding the possibilities of criticism, jazz, and movies, none of them was the successor to anyone else; for better and for worse, they were creating new molds, not filling old ones. Sontag made popular art, movies in particular, a suitable subject in serious discussions of art, literature, and philosophy, while Godard, apart from popularizing jump cuts, introduced those discussions into movies; Davis introduced scales or modes as a basis for improvisation, which eventually made other kinds of jazz possible, such as certain long works by John Coltrane. Their would-be successors, however, are generally heralded not for their innovations but for their cleverness in recycling old works and attitudes, revitalizing their market value. In the present economic setup, which also defines our cultural setup, Godard himself couldn’t qualify as “the new Godard,” even though he continues to be an innovator, because “the new Godard” mainly means the old Godard three decades later.

You won’t find any serious discussion of art, literature, or philosophy or any serious technical innovations in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. But you will find an allusion to Anna Karina’s dance around a pool table in Godard’s Vivre sa vie and some dandyish dialogue from two hit men that may remind you of Jean-Paul Belmondo in Breathless — dialogue that includes an extended discussion about the difference between McDonald’s Quarter Pounders in Amsterdam, Paris, and the United States. If you can’t figure out whether this gab (like the debate about Madonna’s “Like a Virgin” that opens Reservoir Dogs) is supposed to be a satiric put-down or a dumb-ass celebration of American self-absorption, that’s undoubtedly because Tarantino’s mode of hipness involves straddling both positions. This choice, more economic than moral or aesthetic, invites both yahoos and snobs into the tent on an equal footing; nobody feels left out, and everyone feels hip. Much the same sort of doublethink in Forrest Gump and Natural Born Killers seems to be contributing to their commercial success: whatever you think is wrong with the world, these movies are here to tell you you’re absolutely right.

Films that feed parasitically on earlier films are nothing new; Godard’s own early films teemed with such references — though they tended to be critical rather than simple replays, and they always rubbed shoulders with countless other cultural references. Hollywood directors since the 60s influenced by Godard, Truffaut, and Resnais began a process of cinematic citation that has escalated up to the present; sequels and spin-offs are part of the same phenomenon. But until fairly recently such references haven’t composed a self-sufficient world of their own. Taxi Driver borrowed some of its plot from The Searchers and some of its stylistic devices from Godard and elsewhere, but aspects of 70s life in Manhattan still managed to leak through.

Forrest Gump, Natural Born Killers, Pulp Fiction, and Ed Wood suggest a new stage in this process — a stage in which the world and the media become not so much interactive as interchangeable and indistinguishable, yielding an all-pervasive zone of perpetual disbelief that simultaneously saturates and alienates the viewer, confusing affect with effect, stylistic flourish with story, morality with attitude. To a greater or lesser extent, all these movies imply that life can be only what we already see in the media; and since what we see there is invariably false and concocted, all that ultimately matters is the stylishness and purity of gestures, not what these gestures yield or produce. Symptomatically, all four movies feature dense, irrational protagonists whose gestures and personalities we’re asked to admire but whose activities — serving in Vietnam, shrimp boating, Ping-Pong playing, jogging, killing for the fun of it, killing for hire, killing by accident, taking drugs, making terrible movies — are essentially absurd; their lives and fortunes are equally illogical, though often fun and glamorous. All four movies purport to be about transcendence and redemption, but it’s only nominally the heroes who are redeemed — they usually end up no wiser than they were at the outset. More centrally it’s the media-saturated viewer whom these charismatic figures are designed to ennoble and justify. For all their kinetic pleasures, these movies offer the comfort of cocoons, richly appointed with the same furnishings we grew up with.

Significantly, the concept of the media-savvy viewer — characterized more by hip attitudes than by concrete information — finds its counterpart among reviewers. Consider the New Yorker‘s Anthony Lane, who last month built an entire review around the erroneous premise that Boaz Yakin, the director of Fresh, was black. This month, writing about Pulp Fiction, he speculates whether it will date as much as “the rolling nudes and long, soporific takes” of Antonioni’s Red Desert, a film that has neither rolling nudes nor long takes. The magazine (and apparently its readers) may be indifferent to such trivia, but they’re not indifferent to Lane’s prose style, which depends on references and asides as carefully planted as Tarantino’s to convey a fashion-plate surface of knowingness; what’s actually known is obviously less important.

Pulp Fiction and Ed Wood strike me as superior to Forrest Gump and Natural Born Killers because they’re less pretentious, less self-righteous, and less hypocritical about the redemption and transcendence they have to offer. Their human resources also run somewhat deeper: Pulp Fiction has more of a head than the other three, Ed Wood more heart. But all four movies gain their distinction largely by flattering our sense of ourselves as media savants, and all are con games to varying extents because they’re predicated simultaneously on our equivalence to the on-screen characters and our innate superiority, since we’re able to see through all their absurdities. In the final analysis, these movies have more to say about us than they do about their makers, and not always to our credit.

Fourteen years ago, when the Toronto film festival still had a sidebar called “Buried Treasures,” selected each year by a guest critic, I was invited to take over that slot. I put together a program called “Bad Movies,” intending to play with the ambiguity of the word “bad” — the only thing these films had in common, apart from the fact that I liked them, was that each of them had been pegged with that label at some point: Leo McCarey’s An Affair to Remember, Jean Grémillon’s Lumière d’été, Elaine May’s Mikey and Nicky, Kon Ichikawa’s An Actor’s Revenge, James B. Harris’s Some Call It Loving, Delmer Daves’s Bird of Paradise, Edward D. Wood’s Glen or Glenda?, Fritz Lang’s The Tiger of Eschnapur and The Indian Tomb, and William Wellman’s Track of the Cat.

This was the theory, at any rate — that all my selections were good movies that had wrongly been considered bad. But in practice, the single smash success of the series, in terms of both attendance and audience response, was Wood’s Glen or Glenda?, a film appreciated by the audience only for its badness. And since then, the evidence increasingly provided by movie fanzines — which by now far outnumber “serious” film magazines — is that among film cultists, bad movies are immensely more popular than good ones. Or, to put it in more concrete terms, at that festival the North American premiere of the penultimate, two-part masterwork of Fritz Lang, one of the greatest filmmakers who ever lived, was much less popular than the latest replay of a low-budget exploitation item by an inept amateur. Both films are campy, highly personal, and characterized by endearing technical flaws, but Wood’s unintentional hilarity counted for more than Lang’s intentional sublimity.

One can see how much this taste has prospered since then by turning to the October issue of Cinefantastique, where no fewer than a dozen articles celebrate various aspects of Ed Wood the cult writer-director-actor, who died in 1978, and Ed Wood the movie. But it’s not as though this relish for badness has any developed definition of goodness behind it. One article heralding the first publication of a nonfiction manuscript by Wood, lovingly reproduced with all its original misspellings, typos, and atrocious grammar, is almost as badly written as the text it’s describing: “The Hollywood Rat Race truly comes into its morbid own in Wood’s closing chapters on writing. Here, Wood’s weirdly touching ineptitude at his own calling reveals itself in almost every dizzying line. Wood on inspiration: ‘It isn’t every morning you get up, sit down with the old pencil and paper and the greatest ideas in the world flow out — more so it is you will sit down and the blank sheet of paper will stare right back at you. An angry something that lays there defying every thought you might have. A white glob starching every urge into a thoughtless plan which means nothing, or little more than nothing.'” However inferior Wood may be to his chronicler in matters of grammar, it’s hard to deny that he’s vastly more expressive.

The cultural and ideological alchemy that has transformed Wood’s miserable, abject failure of a career into the cause for affection and celebration it is today is not a process Ed Wood cares to examine, though it is central to its meaning. The simplest word for this alchemy is mythmaking — specifically of the sort in which the mythical “world’s worst” somehow taps into the posthumous acclamation of his own life and oeuvre and smiles back at us in mutual recognition. The historical stumbling block is that a certain alienation from the media — an alienation unknown to Wood and his original audiences — is the sine qua non of our mythic appreciation today, thereby blocking any real sense of what it meant to be Wood or even to see a Wood movie during the 50s. Without any knowledge or even any visible curiosity about this subject, all that director Tim Burton and writers Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski can do is build a monument to their and our complex sympathies for Wood from the vantage point of today’s alienation and knowingness — not a monument to Wood himself, who remains unknown and unknowable in the very terms of our enjoyment.

A case in point is the movie’s climactic premiere of Wood’s Plan 9 From Outer Space, which the film sets in the Pantages Theater, one of the largest and most opulent movie houses in Hollywood. Rudolph Grey’s Nightmare of Ecstasy, the oral history of Wood’s life and career that Ed Wood purports to be based on, asserts that the shoe-string Plan 9 never played in Hollywood at all, so I asked Burton at the New York Film Festival why he made this radical change. He replied, with no irony whatsoever, that some portions of the movie take place inside Ed Wood’s head, and this is one of them; in other words, he preferred to show us this event as Wood would have imagined it. Of course this idea would never occur to most viewers — especially those who know little about 1959 or Wood — but even more amazing is that Burton can claim with such confidence that he knows the inside of Ed Wood’s head.

Ed Wood doesn’t really give us the inside of Wood’s head, but it does treat imaginatively a number of Wood movies that retain a certain fascination (although in my mind everything after Glen or Glenda? — Wood’s uniquely deranged first feature, a 1953 documentary about transvestites — is relatively esoteric and boring). One of the undeniable pleasures of Ed Wood is its treatment of three features — Glen or Glenda?, Bride of the Monster, and Plan 9 — as holy writ to be lovingly interpreted, imagining how certain scenes were actually shot or, in the wonderful opening sequence, offering a passionate pastiche in Wood’s style. We also get imaginative, sympathetic re-creations of Wood’s freakish milieu, associates, and habits, suggested by various verifiable facts; most impressive of these is Martin Landau’s charismatic, ingenious impersonation of Bela Lugosi and the film’s warm depiction of his friendship with Wood (Johnny Depp). To be sure, much of this interpretation is as mythic as the rest of the film — nothing here indicates that Lugosi was a devout Catholic not prone to swearing, that he was hampered in his acting by his poor grasp of English, and that he was once a vigorous trade-union official back in Hungary. But at least the movie offers us a viable way of imagining the man’s pathos at this terminal stage in his career.

But when it comes to Wood himself, the movie can’t get beyond a mythic depiction of his glee and determination, or the usual lore about his angora fetish and his oddball entourage. Indeed, all that can be furnished of that lore is a series of signals about it designed to set off knowing nods among audience aficionados, creating a jaunty boys’ club atmosphere that seems largely imposed on the material. Also imposed are a nightmarish audience for the premiere of Bride of the Monster (no doubt occurring inside Wood’s mythical head again), in which the hostile patrons are jeering before the movie even comes on, and a mythical encounter with Orson Welles (the worst meets the best) to seal Wood’s future immortality. And to spare the viewer the embarrassment of burrowing through the final 19 years of Wood’s life — a grim tale of alcoholism, poverty, trash novels, and porn loops, encapsulated in one of the end titles — the movie chooses to take leave of him in 1959. In short, because the movie is incapable of imagining a precamp context for Wood, it has to import today’s audience for his movies — contemptuous at one premiere, reverential at the other — back into the unknowable 50s, along with 90s versions of Welles and Lugosi. In this way Wood’s alienation and our own are both validated in the same charmed (and charming) gesture: his doomed innocence becomes our doomed sophistication, and vice versa, and we all go happily to hell together, borne aloft by Burton’s warm feeling for outcasts.

***

If the historical past looms as a lost continent to Burton, morality seems to have a comparable remoteness to Tarantino. Perhaps the reason is his well-advertised artistic formation as a video-store clerk — a couch-potato savant par excellence — for whom instant-action kicks and their usual antihumanist justifications define the boundaries of any moral universe. “Redemption” in this context invariably requires vats of blood, disposable corpses, and guys doing guy things with other guys (such as producing the vats and corpses). And invariably such redemption is signaled by nudges to the academically attentive: for example, a license plate that says “GRACE” on the back of a redneck’s filched chopper. Homoeroticism for heterosexuals is the order of the day, served up with the kind of gusto designed to make little boys squeal with delight.

Like Reservoir Dogs before it, Pulp Fiction defines transgression and attitude largely through language. Most noticeably, it celebrates racial verbal abuse within an elaborately and strategically muddled PC context. By my count, Pulp Fiction employs the word “nigger” at least 16 times — spoken sometimes by black characters and sometimes by whites, always to great effect. But it does this within a racially complicated narrative framework: black and white hit men (Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta) work for a black boss (Ving Rhames) who has a white mistress (Uma Thurman); to complicate matters further, Tarantino’s own bit character — who says “nigger” more often and more gratuitously than any other white person in the movie — is married to a black nurse.

All these narrative elements are possible, if not plausible, reflections of interactions that might take place in the real world, but Tarantino’s point in using them clearly isn’t to say anything about reality but to produce certain effects. When asked in Cannes why the word “nigger” cropped up so often in the film, Tarantino replied that he wasn’t really sure where it came from, but then added ingenuously that he liked to think that if the word were repeated often enough it would lose all its meaning and potency. A poignant prospect: if such a thing should happen through Tarantino’s noble efforts, it might actually put him out of business — unless, of course, he turns to “gook,” “spic,” “wop,” “chink,” or “kike” to furnish his future screenplays with comparable spiky, crowd-pleasing effects.

I hasten to add that Pulp Fiction is the most thoroughly and consistently entertaining Hollywood picture I’ve seen this year, brimming with energy, star power, humor, and ingenuity. It’s only when I start to ponder the giddy moral vacuum that produces and validates much of its entertainment — and the dearth of wisdom or vision yielded by these kicks — that my enthusiasm starts to sour.

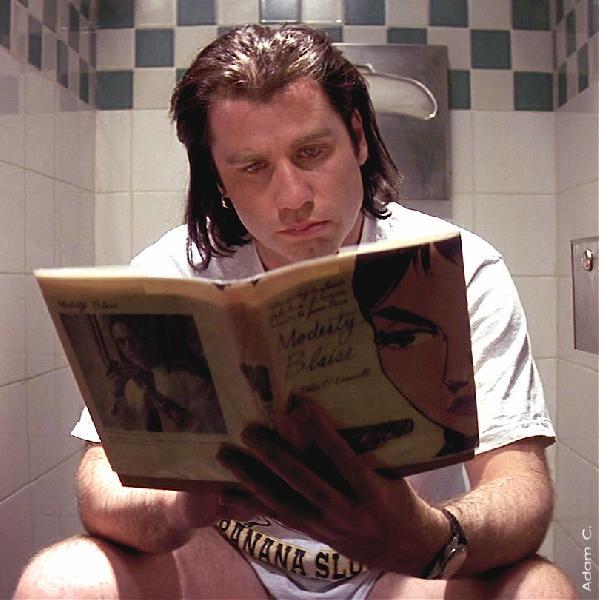

Like the racial epithets, Tarantino’s treatment of coke and heroin is similarly styled for kicks while also being tricked out with certain checks and balances (shooting up is fetishized like a perfume ad, but snorting leads to an overdose). The same can be said of Tarantino’s cherished theme of anal penetration, which figures here as mean slang, the central gag in a ponderous Christopher Walken monologue, and a gratuitous rape during an already ridiculous basement sequence showing how mean some hillbillies are — only to be wistfully recalled, like a favorite musical theme, by two sessions with Travolta on the toilet.

It’s true that some of these details, unlike the “nigger” mantra, provide Tarantino with some of his much-applauded and genuinely enjoyable plot swerves. The point is that all this “liberating,” golly-gee narrative promiscuity is so cynically, nihilistically calculated that it leaves a bad aftertaste. Though this is another boys’ club movie, Pulp Fiction has enough generosity, as critic Godfrey Cheshire points out, to give nearly every one of its characters — including three of its four female characters — a second chance. It also has enough wit to scramble its interlocking stories, for maximum effect and meaning. But all these tales, all the characters and their second chances, derive their meaning, their impact, and even their limited truth from other movies and TV shows. To call this the best that American filmmaking can do at the moment, as the Cannes jury and most reviewers have been doing, is another way of saying that American filmmaking can’t do much at all — certainly not deal with the world that’s right in front of us, as Charles Burnett’s powerful forthcoming The Glass Shield does. (Shown at many of the same festivals as Pulp Fiction, it’s gotten very little attention, perhaps because it treats racism honestly rather than as an excuse for cheap thrills.) Even the spiritual awakening at the end of Pulp Fiction, which Jackson performs beautifully, is a piece of jive avowedly inspired by kung fu movies. It may make you feel good, but it certainly doesn’t leave you any wiser.

On the other hand, Tarantino’s flair for unorthodox plot construction, goofy dialogue, and dreamy interludes always keeps the viewer alert. The funny quasi-philosophical dialogues between hit men Jackson and Travolta about such matters as the definition of a TV pilot, the relative intimacy of foot massages, what constitutes a miracle or divine intervention, and the cleanliness of pigs and dogs are like extended musical vamps that playfully retard the action, meanwhile establishing motifs of their own to be developed later; and a visit by Travolta and Thurman to a lush 50s-style hamburger joint that ends with a wonderful patch of dancing not only becomes another gleeful interruption but allows for more spot-the-reference games.

All this suggests another legitimate parallel with early Godard — the director’s determination to cram everything he likes into a movie. But the differences between what Godard likes and what Tarantino likes and why are astronomical; it’s like comparing a combined museum, library, film archive, record shop, and department store with a jukebox, a video-rental outlet, and an issue of TV Guide. The fact that Pulp Fiction is garnering more extravagant raves than Breathless ever did tells you plenty about which kind of cultural references are regarded as more fruitful — namely, the ones we already have and don’t wish to expand. If the studios and their many publicists (including reviewers) get their way, we can expect to see a lot more of such references — maybe even on an endless porn loop, which would finally validate the end of Ed Wood’s career as well as the beginning.