Written for a Persian collection about Béla Tarr, published in May 2016. — J.R.

My first encounter with the work of Béla Tarr was Damnation (1987), seen in 1989, followed soon afterwards by Almanac of Fall (1984), but the point at which I became an acolyte rather than a mere fan was Sátántangó (1994), which remains for me the towering pinnacle of his work. Other favorites include The Turin Horse (2011) and his nearly impossible-to-see short film The Last Boat (1989), but I know plenty of other viewers who were first won over by Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), and another good starting point might be Tarr’s 1982 production of Macbeth (1982), made for Hungarian television in only two shots.

Most of his films qualify as black comedies filmed in black and white, spiritual without being religious and peopled most often by grubby and not especially honorable individuals who are followed with lengthy takes and elaborately choreographed camera movements that implicate the viewer in their activities and thwarted destinies. Starting with Damnation, they are mostly written by the great Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai, whose endless and labyrinthine sentences in his novels are as relentless and as passionately serene as Tarr’s camera movements.

After The Turin Horse, Tarr decided to stop making films and start producing (or, more precisely, nurturing and instructing) filmmakers instead, which led to his founding a rather remarkable international film school in Sarajevo in 2013 called Film.Factory, where I have already had the privilege of teaching on four separate occasions, each time for two very intense weeks.

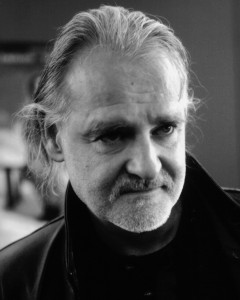

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Chicago, 4 February 2016