From the Chicago Reader (September 8, 1995). — J.R.

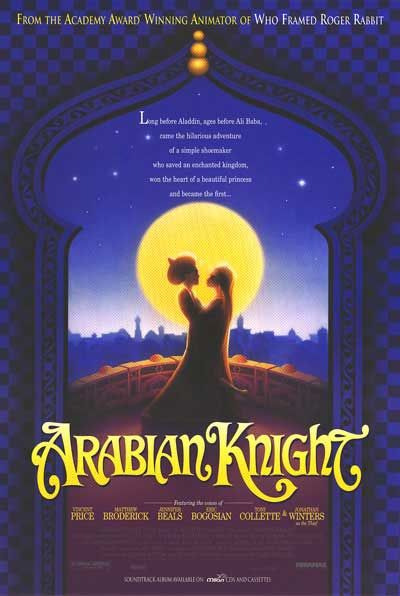

Arabian Knight

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Richard Williams

Written by Williams and Margaret French

With the voices of Vincent Price, Matthew Broderick, Jennifer Beals, Eric Bogosian, Toni Collette, and Jonathan Winters

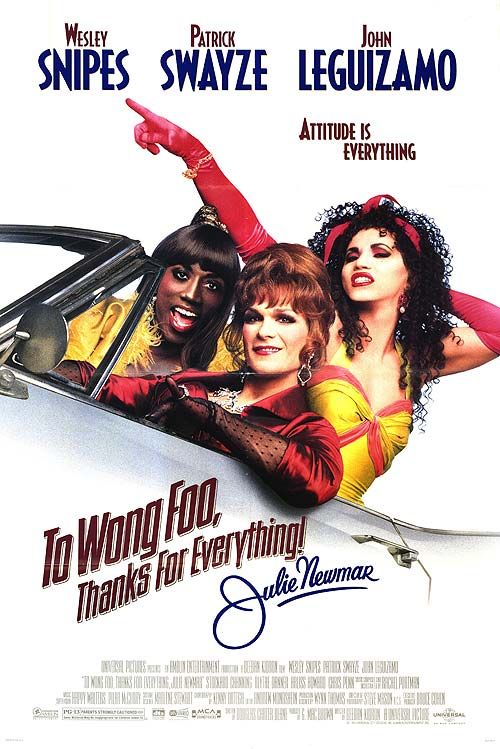

To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar

No stars (Worthless)

Directed by Beeban Kidron

Written by Douglas Carter Beane

With Wesley Snipes, Patrick Swayze, John Leguizamo, Stockard Channing, Blythe Danner, Arliss Howard, Jason London, and Chris Penn.

It might be argued that a talent for abstract thought defines the radically different achievements of Arabian Knight and To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar. In Arabian Knight–a wildly imaginative and somewhat delirious animated feature that’s reportedly been in the works for over a quarter century — it’s a talent for graphic abstraction, a talent that is its own reward; this movie takes the highly dangerous step of pursuing formal beauty above all else, story and characters be damned. By contrast, in To Wong Foo — a terribly written, terribly directed, terribly designed, and for the most part terribly acted (if nobly intentioned) comedy –i t’s a talent for pure concept: three drag queens driving from New York to Hollywood enlighten bigoted middle Americans on the subjects of style and beauty. Here the concept is everything, and the implementation and illustration of that concept, including the movie’s own style and beauty, count for absolutely nothing. If Arabian Knight suggests that doodling is a high art, To Wong Foo calls to mind an astute observation by the late Mary McCarthy: “Where for a European, a fact is a fact, for us Americans, the real, if it is relevant at all, is simply symbolic appearance.”

Arabian Knight, once titled The Cobbler and the Thief, started out as a labor of love for Richard Williams, a Canadian-born animator who after brief stints with Disney and UPA settled in England in his early 20s and built his own studio there. He’s best known for his TV commercials, the title sequences to What’s New, Pussycat? and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, and the occasions for his two Oscars, A Christmas Carol (1971) and the animation in Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988). Williams had been working on The Cobbler and the Thief since 1968, apparently whenever he wasn’t busy with more lucrative projects, but eventually he lost creative control over it, and it’s been through many vicissitudes since. In the final credits, three individuals not including Williams and his cowriter Margaret French are credited with “additional dialogue,” and some of this dialogue is noticeably offscreen or not in sync. Miramax released the film — which runs a little over an hour, about the same length as Dumbo — two weeks ago as if it had the measles, at least as far as anyone in the press was concerned.

To Wong Foo, on the other hand, is being released with the full support and endorsement of its production company, Amblin, and its distributor, Universal. In my mind the film is an inferior, more expensive, Americanized version of The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, but Universal and Amblin insist that it’s based on an original screenplay by playwright Douglas Carter Beane, who “first got the idea for the story when he was home for the Easter holidays. ‘My mother and I were watching RuPaul on MTV,’ he says, ‘and my mother said, “You know, she’s a lovely girl, but she has terrible proportions.” And it suddenly dawned on me: A lot of Americans can’t tell who’s a woman and who’s a drag queen.'”

It’s crucial to the movie’s intended appeal, however, that no one in the audience could ever mistake Wesley Snipes, Patrick Swayze, or John Leguizamo — who are dressed in drag throughout — for a woman; only the hicks they run into on the road and get to know in Snydersville, Nebraska, are fooled. Rumor has it that this movie tested extremely well in some conservative parts of California, and I’d wager that the slapstick premise of seeing well-known actors like Snipes and Swayze in drag is central to its drawing power. The fact that none of the drag queens ever asserts himself as a homosexual helps keep the masquerade unthreatening even for homophobic viewers. And the fact that no one, straight or cross-dresser, is shown behaving like a human being keeps it even safer.

This abstract notion of humanity and human behavior is central to the movie. Snipes never plausibly impersonates a woman even when he’s quiet and standing still, and Swayze at his most resourceful impersonates Jack Lemmon impersonating a woman in Some Like It Hot, which means that his impersonation is still at one remove. Leguizamo fares slightly better, but English director Beeban Kidron appears to have been so distracted in her handling of the actors that even veterans as talented as Blythe Danner and Stockard Channing seem ill at ease. And Kidron’s feeling for American small-town life — what it looks, sounds, and feels like — seems to border on the nonexistent.

If one sees To Wong Foo as a cartoon, perhaps it’s easier to accept the film’s grotesqueness. I suppose the loud laughter I heard from some people at the preview screening could be partially explained this way. But any cartoon worth its salt, Arabian Knight included, has a sense of style and rhythm and color, none of which I could discern here. All I could find was the sheer ugliness of assertiveness and ostentation unaccompanied by any sense of style, wit, or color coordination that might personalize the expressiveness, even as camp. To my mind, To Wong Foo simply proves the power of contemporary American audiences to think conceptually — a power undoubtedly nurtured by the visual and verbal poverty of TV, which compels viewers to fill in the blanks in order to make any sense out of what they’re watching. (The David Letterman show and a good many sitcoms rely so heavily on a self-referential context that, unless you’ve watched them for a while, they can seem as abstract and symbolic as semaphore.)

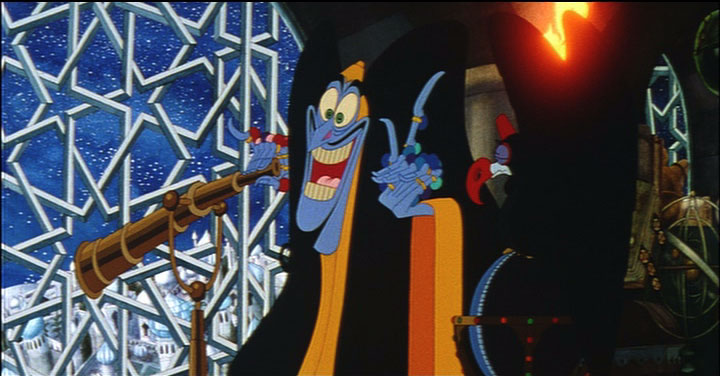

I can’t say that I became very involved in the story of Arabian Knight, but in a way my eyes were too delightfully occupied to permit such an indulgence. The plot, such as it is, has something to do with a Baghdad cobbler named Tack (Matthew Broderick), a hapless hero who appears mainly in black and white, unlike everyone else; Princess Yum-Yum (Jennifer Beals), whom he falls for; a bumbling thief (Jonathan Winters) whose head is perpetually encircled by flies or fleas and whose pole-vaulting endeavors recall those of Wile E. Coyote in Road Runner cartoons; and a villain named Zigzag (the late Vincent Price) who more or less plays Merlin to Yum-Yum’s father.

The main dish here is Williams’s two-dimensional visual style, which evokes at various times and sometimes simultaneously Persian art, UPA cartoon characters of the 50s like Mr. Magoo and Gerald Mc-Boing Boing, op art, the graphic works of M.C. Escher, medieval tapestries, surrealist painting, a few Disney cartoons at their most free-form (e.g., the dance of the pink elephants in Dumbo and a sizable stretch of The Three Caballeros), and Edwin A. Abbott’s novel Flatland. Surely it’s no coincidence that one of the characters is called Mighty One-Eye. The sense of a crowded, flat decorative surface is fairly constant, if constantly changing: if the great visionary Armenian filmmaker Sergei Paradjanov (Sayat Nova) had ever created a cartoon, it might have looked like this one.

So much for the dazzling formal beauty of Arabian Knight, which is at the other end of the spectrum from the strident ugliness of To Wong Foo. But the story, characters, and “message” of Arabian Knight — the things that in To Wong Foo are completely clear, if idiotically simple — often border on incoherence; the filmmakers’ love of beautiful surfaces seems to have excluded the cultural, historical, social, or psychological consistency that might have given some structure to the narrative. The story is supposed to be taking place in ancient Baghdad, but the way the title crosses “Arabian Nights” with “Knights of the Round Table” only begins to suggest the film’s confusion.

This is an ancient Baghdad where a plane can be seen briefly buzzing around and there’s a gag reference to Mel Torme. (Admittedly such anachronisms also abound in the Disney Aladdin, but there Robin Williams, playing a genie who transcends time and space, functions like a veritable Cuisinart — or TV set — blending them all together, not always happily.) This is also a Baghdad where an English-sounding character named Roofless can sing hilariously with his fellow English-sounding brigands about “What happens when you don’t finish school,” where the villain Zigzag can be pulled along in a sled by alligators, where a golden Buddha in a witch’s lair carries a ruby on his head, and where a buzzard named Phido (Eric Bogosian) can complain, “I’m so hungry I could eat a vegetarian.”

This movie is so whacked out, so abstract in its approach, that one sequence actually pivots around a three-way pun involving the hero Tack, an actual tack, and the word “attack,” and the thief winds up stealing the words “the end” at the picture’s close. What ultimately limits Arabian Knight is what I also relish about it: it goes everywhere, expanding in all directions. Alas, this kind of beautiful insanity tends to be frowned on by the dull business types who determine the fates of movies, so a picture like this one gets sneaked out in the dead of night while the arrival of the stupid and ugly but crystal-clear To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar gets trumpeted from the rooftops.