From Monthly Film Bulletin, September 1975, Vol. 42, No. 500.

It’s good to see Norman Mailer’s first three features just out in a two-disc DVD set from Eclipse (it would be great if Criterion could eventually do the same for Susan Sontag’s three fiction features), even though I regret that my two favorite Mailer films — his untitled, ten-minute experimental short from 1947 (recently discovered by archivist Michael Chaiken, who wrote the excellent and provocative notes for the Eclipse set, and which I saw last July at Il Cinema Ritrovato) and Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987) — aren’t included. (Admittedly, I haven’t yet seen all of Maidstone, which Chaiken makes the most claims for, so these rankings on my part are still subject to revision.)…In his Eclipse notes, Chaiken describes Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Stand Up? [sic] as “a filmed counterpart to The Armies of the Night“, which parallels my own observation here. — J.R.

Will the Real Norman Mailer Please Stand Up

Canada, 1968

Director: Dick Fontaine

Dist—The Other Cinema. p.c–Allan King Associates. For National

Educational Television, British Broadcasting Corporation, Canadian

Broadcasting Corporation, Bayerischer Rundfunk. exec. p–Allan King,

Roger Graef. p/sc—Dick Fontaine. ph–Richard Leiterman. In colour.

ed—Stephen Milne. Song–“The Eve of Destruction” by and sung by

Bob Dylan. sd–Russel Helse, Mike Billing. p. assistants–Jeffrey Edward,

Gwen Gillie, Judith Marriott, Mark Peploe, Toni Trow. with–Norman

Mailer, James Toback, Robert Lowell, Dwight Macdonald, Beverly

Bentley, Merv Griffin, Barry McGuire. 2,182 ft. 61 mins. (16 mm.).

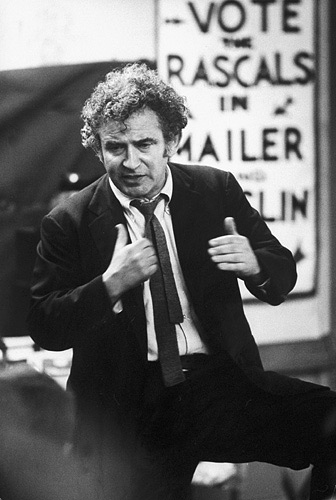

Norman Mailer is presented in a series of his public roles, each

identified by a superimposed title and intermixed with verbal and

visual snatches of Barry McGuire, a fast-talking Washington disc

jockey who occasionally alludes to the ‘media events’ featuring

Mailer. THE NOVELIST: Mailer is interviewed on TV by James

Toback after the publication of Why Are We in Vietnam? and talks

about modern heroes. THE DIRECTOR: He prepares a line-up

scene in his film Beyond the Law. THE ACTOR: He performs in the

scene. THE ACTOR & HIS WIFE: A different sequence in the

finished film, with Mailer and his wife Beverly Bentley quarreling

in a restaurant. THE CITIZEN: Mailer addresses a group of draft-

card burners in Washington prior to the October 1967 March to the

Pentagon. THE MASTER OF CEREMONIES: Drunk on bourbon, he

imitates Lyndon Johnson and introduces Robert Lowell at a rally

before the march; this is followed by a brief quote from Time

Magazine’s coverage of the event. An untitled sequence details

Mailer’s participation in the march itself and his subsequent

voluntary arrest. VIRGINIA — THE STATE PENITENTIARY:

Mailer emerges from prison and is questioned by reporters. THE

PREACHER: He concludes his statement by dictating a “sermon”

about Jesus Christ and the war in Vietnam to the journalists; later

he reads the Washington Post‘s coverage of this speech. THE

CELEBRITY: He appears as a guest on The Merv Griffin Show,

introduced as the author of What Are We Doing in Vietnam?, and

proceeds to deliver a heated denunciation of the war; in a bar, men

are shown watching the TV programme and then making semi-

coherent comments about Mailer after one of them angrily

disconnects the set.

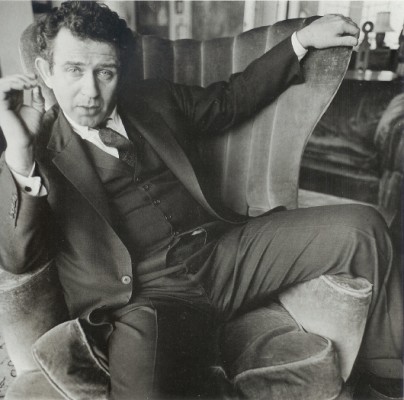

A uniquely valuable document and educational tool, Dick

Fontaine’s carefully crafted portrait of Norman Mailer in 1967-8

offers at once an essential companion piece to Mailer’s book The

Armies of the Night and an intriguing contrast to Godard and

Gorin’s Letter to Jane — with which it might make a fruitful double-

bill — in its broaching of questions about the role of intellectual

media figures in protesting U.S. involvement in Vietnam. From

‘THE CITIZEN’ onwards, all the episodes described above receive

independent treatment in Mailer’s book; and because both book

and film are concerned with the impact and distortion of events in

and through the media, a dense and ambiguous interplay is set up

between the versions offered by (1) the media, in the form of TV

appearances, radio announcements and newspaper and magazine

coverage, much of which is cited by book and film alike, using the

same examples, (2) Mailer’s alternate reports in the book of his

speeches and the various events, and (3) the film’s own rendering of

the above phenomena, which often differs sharply from (1) and (2).

For one thing, Fontaine has altered the chronology of some events-

the filming of Beyond the Law occurred after the Pentagon March,

not before, and the evening rally preceded rather than followed

Mailer’s address to the draft-card burners — and has apparently

staged certain others (Mailer reading the Washington Post, the

barroom conversation, a few of McGuire’s interjections). On the

other hand, many of the actual speeches delivered by Mailer in the

film come across quite differently from either the media or the Mailer

reports of them, in detail as well as in overall effect, suggesting how

readily one man’s documentary can become another man’s

confection. A particularly ironic aspect of the film’s title is the fact that

the “real Norman Mailer”, i.e. the writer — the single role which

makes all the others possible or plausible — is the role to which

film and media seem least attentive: Why Are We in Vietnam? is

used as a topical launching pad in one TV appearance, the title is

blithely mangled in another, and The Armies of the Night (which

presumably appeared after the film was completed) is not mentioned

at all. In terms of the contrasts implied by Fontaine’s arrangement

of events, Mailer appears in turn pompous, modest, stupid, brilliant,

blustering, graceful, incoherent and eloquent from one sequence to

the next, like a perpetually developing fictional character. As in The

Armies of the Night, a concentrated focus on these juxtapositions

effectively renders the Vietnam war peripheral, or at any rate

secondary to the issue of how a famous author bears witness to it: “I

wasn’t Lyndon Johnson’s alter-ego for nothing” Mailer remarks on his

way out of jail, neatly fusing his solipsism with the film’s own media

conceits (while Fontaine alternately links him with the disc jockey

McGuire). All this transpires under the late Sixties spell of Marshall

McLuhan, which guarantees a perpetual confusion between

diagnosis and symptom. (It is worth noting that Will the Real Norman

Mailer Please Stand Up was made for TV networks in four countries,

and is thus an integral part of the pop media it describes.) Yet taken

in conjunction with Mailer’s book it offers a fascinating

demonstration of how all versions of an event — no matter how

conscientious or ‘truthful’ — are none the less versions, and potential

grist for any number of independent mills.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM