The following was written in February 2009 for a projected volume on Stanley Kubrick that was being prepared at the time by the Chicago-based magazine Stop Smiling, which commissioned this and a few shorter pieces by me for it, including a short “sidebar” text about James Naremore’s On Kubrick, written in April 2010, which I’ve appended to our exchange. [2023: An expanded second edition of this valuable book has recently appeared.] For a variety of reasons, including the discontinuation of the magazine, the book never appeared, and the editor, James Hughes, gave me permission to post it here, originally in September 2013….I obviously guessed wrong when I surmised here that Kubrick’s family would probably keep Fear and Desire “off the market”. — J.R.

Early Kubrick: An Exchange

By Jonathan Rosenbaum and James Naremore

Dear Jim,

As you note in your book on Kubrick, he removed his first feature, Fear and Desire (1953), from circulation at some point during the 60s. I know this couldn’t have been during the early 60s because I saw it for the first time in 1961 or ‘62, at the Charles Theater, a legendary, eclectic arthouse on the Lower East Side, when I was a freshman at NYU. Read more

Reprinted from my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles, but with illustrations added. (The first of these is a photo taken near Antibes, France, where the revamped Touch of Evil was scheduled to premiere, until Beatrice Welles threatened a lawsuit and halted the screening. Much later, she sent a letter of apology to Janet Leigh that I got to read at one point. Fortunately, this didn’t prevent me from enjoying a wonderful day with Janet Leigh, her daughter Kelly, and several others on the Côte d’Azur, capped by this photo of the Touch of Evil re-edit “crew” and then followed by a memorable dinner.)

The following —- an account of my work as consultant for Universal Pictures on the re-editing of Touch of Evil in 1997-98, based on a studio memo -— is the only thing I’ve ever written for Premiere. I knew one of the editors, Anne Thompson, from her previous stint as assistant editor at Film Comment, and when I proposed this piece to her, she checked with other editors at the magazine and reported back that there was a lot of enthusiastic interest. When I asked her what approach I should take, she urged me to write a first-person account of my experience of the project from beginning to end, which yielded a first version. Read more

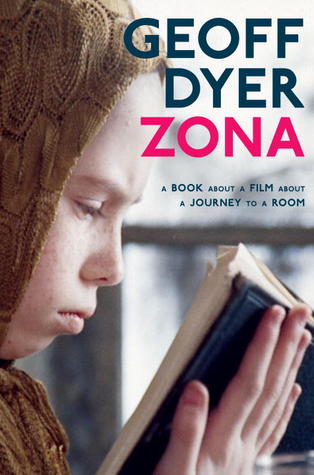

A slightly edited version of this article entitled “Devotional Reading” appeared in the November-December 2012 issue of Film Comment. For whatever it’s worth, I find Geoff Dyer’s taped interview about Stalker on Criterion’s Blu-Ray more perceptive than anything in this book. I guess he’s had more time to think about it by now. — J.R.

There are at least two intriguing recent trends reflected in the publications of Geoff Dyer’s Zona: A Book about a Film about a Journey to a Room (New York: Pantheon, 2012) and Adam Mars-Jones’s Noriko Smiling (London: Notting Hill Editions, 2011) — book-length studies of masterpieces (Stalker and Late Spring, respectively) and film criticism by amateurs (both of them prestigious literary Brits). A couple of much older attitudes underlying both is a view of cinema as literature by another means and, conversely, a view of film analysis as a literary and linear pursuit.

It’s obvious that what links these two trends historically is the phenomenon of home viewing, which has made every viewer a potential “expert” for the first time. Prior to VCRs and DVD and Blu-Ray players, the only tools available for studying films at length were 16 mm projectors and moviolas, most often belonging only to “professionals” of one kind or another. Read more