From the Chicago Reader (September 1, 1988). — J.R.

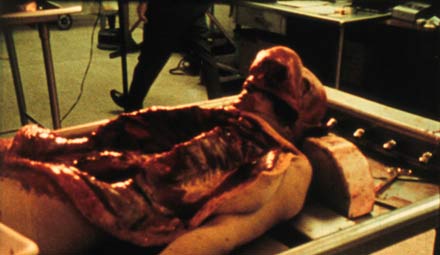

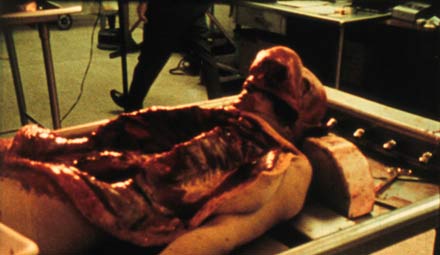

Stan Brakhage’s convulsive personal and silent documentary about a Pittsburgh morgue, made in 1971, is one of the most direct confrontations with death ever recorded on film. Included on the same program — along with a lecture by Chuck Kleinhans, professor of film at Northwestern University — are three other shorts that are not conventionally regarded as horror films, but that will be considered in relation to that genre: Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid’s ground-breaking experimental film Meshes of the Afternoon (1943); Chris Marker’s innovative science fiction film La jetee (1964), which tells its story almost exclusively in stills; and Celia Condi’s 1982 combination of soap-opera characters and dark humor, Beneath the Skin. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (April 8, 1988). — J.R.

Alain Resnais’ masterpiece, easily his best film in years, is bound to baffle spectators who insist on regarding him as an intellectual rather than an emotional director, simply because he shares the conviction of Carl Dreyer and Robert Bresson that form is the surest route to feelings. In his 11th feature, he adapts a 1929 boulevard melodrama by a forgotten playwright named Henry Bernstein, and holds so close to this “dated” and seemingly unremarkable play that theatrical space and décor — including the absence of a fourth wall — are rigorously respected, and shots of a painted curtain appear between the acts. None of this is done to strike an attitude or “make a statement”: Resnais believes in the material, and wants to give it its due. Yet in the process of doing this, he not only invests the original meaning of “melodrama” (drama with music) with so much beauty and power that he reinvents the genre, but also proves that he is conceivably the greatest living director of actors in the French cinema, and offers a way of regarding the past that implicitly indicts our own era for myopia. (Mélo is certainly a film of the 80s and not an antique, but it may take us another 20 years to understand precisely how and why.) Read more

This was written on February 25, 2007, provoked by yet another case of a Wellesian pseudo-expert bonding with another non-expert to lay down what is supposed to be the definitive history and wisdom on the subject. Sanford Schwartz did write me a short, polite, private response that, as nearly as I can recall, didn’t really engage with any of my arguments. — J.R.

To the Editors:

I’m grateful for Sanford Schwartz’s article about Orson Welles in the March 15 issue of the New York Review of Books, which strikes me as being far more sensitive to Welles’s work and some of the issues posed by his troublesome career than most pieces I’ve read on the subject by nonspecialists. Even if Schwartz’s ideas about Welles as a proto-surrealist are more provocative than convincing to me, they do lead to some arresting observations about his visual style. So I hope he’ll forgive me for pointing out an error in his piece and a few assertions that I believe are misleading. They all derive from confusions that invariably greet any effort made to describe Welles in relatively simple terms.

First, the error: “Although [Welles] was involved with many films that for one reason or another weren’t brought off, he actually finished only twelve, a group that includes the fairly short F for Fake and The Immortal Story, both made for TV.” Read more