This appeared Cinema Scope no. 11 (summer 2002).Thanks to Francois Thomas in helping me clean up my German and French. — J.R.

“You can’t smell email,” Raúl Ruiz insisted to me the night before we had this interview at the 2002 Rotterdam Film Festival, explaining to me why he didn’t have any truck with the Internet. He added that lately he’s been collecting various first editions, excommunications, and death sentences, many of them from the 19th century and earlier, and he can smell all of them.

At first I was surprised by this old-fashioned form of resistance, but then the more I thought about it, the more I realized that Raúl is basically a 19th century figure. His largely Borgesian canon of 19th and early 20th century English and American writers (Chesterton, Stevenson, Wells, Harte, Hawthorne, Melville, et al) and his taste for rambling narratives and tales within tales smacks of a Victorian temperament.

I first encountered Ruiz’s work during my first trip to the Rotterdam Film Festival, in 1983, and it was there where we first became friends three years later —- as well as where we had this interview on January 26, in the lobby of the hotel where we were both staying. Read more

From the Autumn 1984 Film Quarterly. I reviewed this book at Biskind’s request, and my position was hampered by the fact that he was the main editor of American Film at the time, where his commissions were essential to my livelihood. Our relationship became even more strained after I was all set to review the book and he then informed me that he wished I weren’t reviewing it. — J.R.

SEEING IS BELIEVING: How Hollywood Taught Us to Stop Worrying and Love the Fifties By Peter Biskind. New York: Pantheon Books, 1983. $22.95 cloth, $10.95 paper.

The first thing to be said about Peter Biskind’s ambitious and long-awaited study of ideology in Hollywood movies of the fifties is that it can’t be dipped into at random with out a considerable amount of confusion setting in. Without the benefit of Biskind’s careful construction and preparation, the unwary reader who plunges in midstream is bound to be bewildered or dismayed by many of the political labels, whereby Thieves Highway, for instance, is designated as a “right-wing film,” or High Noon and The Blob as “radical films.” Even in the Introduction, which tends to be more cautious than the rest of the book, several eyebrows are likely to be raised by the following sentence: “The films of Robert Aldrich can usually be counted on to be somewhere on the left, just as the films of Elia Kazan are frequently in the middle, while those of John Ford are to the right of his and those of Alfred Hitchcock are to the right of his. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 8, 1994). Also reprinted in my collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

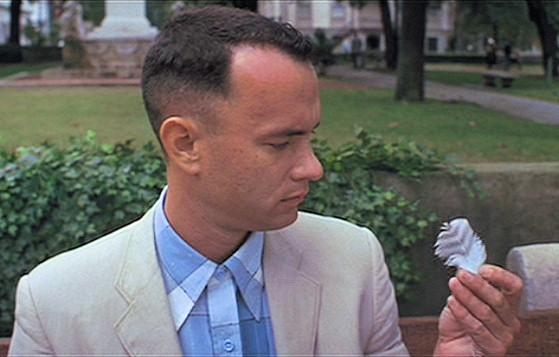

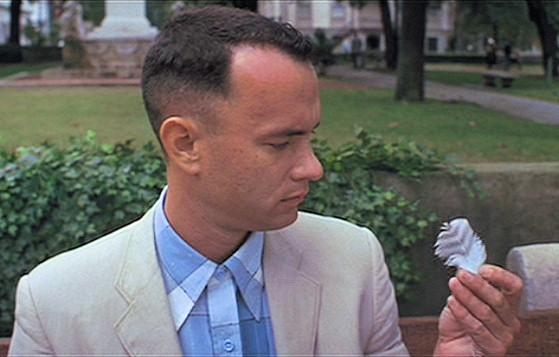

** FORREST GUMP (Worth seeing)

Directed by Robert Zemeckis

Written by Eric Roth

With Tom Hanks, Robin Wright, Gary Sinise, Mykelti Williamson, Sally Field, Michael Humphreys, and Hanna Hall.

In the opening shot of Forrest Gump — a movie that might be described as Robert Zemeckis’s flag-waving Oscar bid — the camera meticulously follows the drifting, wayward trajectory of a white feather all the way from the heavens to the ground, just beside the muddy tennis shoes of the title hero (Tom Hanks). Forrest Gump, a slow-witted, sweet-tempered, straight-shooting fellow from Alabama with an IQ of 75, is waiting for a bus in a small park in Savannah, Georgia. Picking up the feather and placing it inside a book, he proceeds to recount his life story to various passing strangers; in the film’s final shot, over two hours later, we see a breeze carry the same white feather up and away.

These framing shots — a poetic statement about the vicissitudes of chance, how histories are made, unmade, and remade — are meant to say something about a half-century of American life, from the 40s to the present; and the tragicomic life of Forrest Gump, a saintly fool, is meant to embody those years. Read more