Commissioned by MUBI Notebook and posted there on June 19, 2020. — J.R.

There’s a lot of confusion about what improvisation in movies consists of — when it is or isn’t used, and sometimes what it means when it is used. Those who think that the dialogue in Orson Welles’ The Other Side of the Wind is improvised don’t realize that the screenplay by Welles and Oja Kodar with that dialogue was published years ago, long before the film’s posthumous completion. It’s worth adding, however, that the film’s mise-en-scène was improvised by Welles on a daily basis. Similarly, those misled by director Robert Altman’s dreamy pans and seemingly random zooms in The Long Goodbye into concluding that the actors must be inventing their own lines are ignoring the careful work done by screenwriter Leigh Brackett, not to mention Raymond Chandler.

Many of those who associate improvisation with John Cassavetes — ever since he brazenly concluded his first feature, Shadows, with the printed title, “The film you have just seen was an improvisation” — don’t seem to realize that, long after the actors did their initial improvs in Cassavetes’ Manhattan acting workshop, most of the lines were set and even written down before the cameras started rolling. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, February 25, 2000. This essay is also reprinted in my collection Essential Cinema. — J.R.

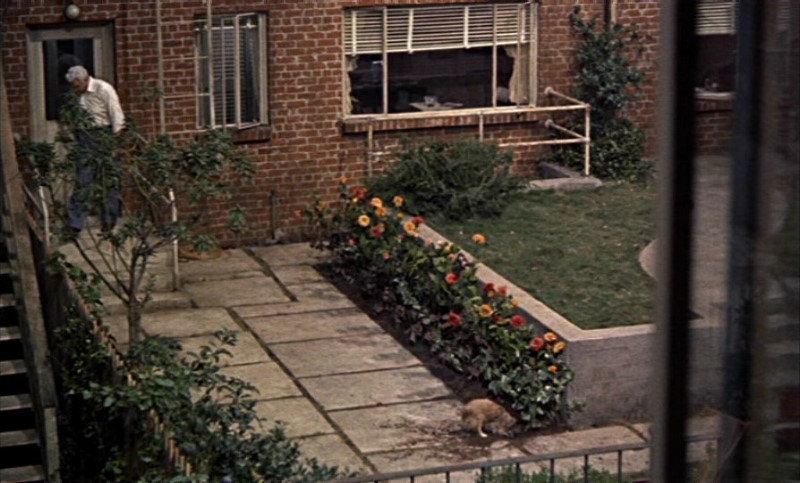

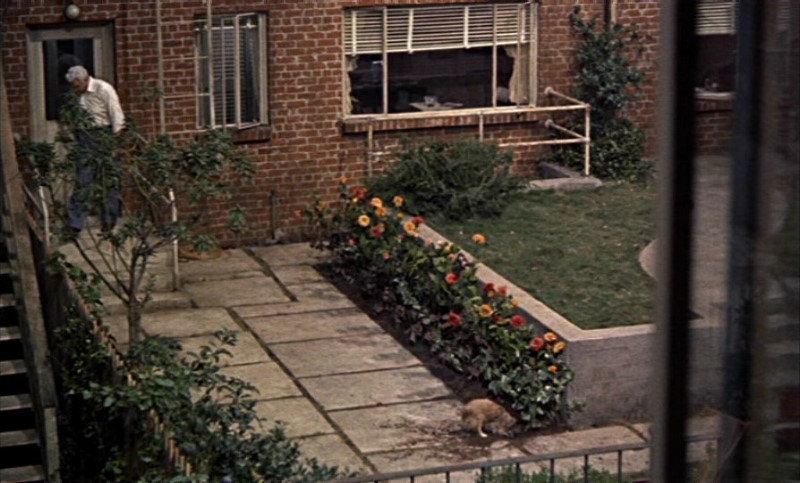

Rear Window

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Alfred Hitchcock

Written by John Michael Hayes

With James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Thelma Ritter, Raymond Burr, Wendell Corey, Judith Evelyn, Ross Bagdasarian, Georgine Darcy, and Irene Winston.

Alfred Hitchcock’s greatest movie, Rear Window, is as fresh as it was when it came out, in part, paradoxically, because of how profoundly it belongs to its own period. It’s set in Greenwich Village during a sweltering summer of open windows, and it reeks of 1954. (A restored version, by Robert A. Harris, opens this week at the Music Box, and it’s so beautiful and precise it almost makes up for his botch of Hitchcock’s Vertigo a few years back.)

Peter Bogdanovich notes in Who the Devil Made It that Hitchcock “didn’t use a score” in the movie, “only source music and local sounds,” which isn’t exactly true. In fact, we get quite traditional theme music from Franz Waxman behind the opening credits, and, more important, the film subtly integrates hit tunes of the mid-50s into the ambient sound track, most noticeably “Mona Lisa” and “That’s Amore,” which was introduced the previous year by Dean Martin in another Paramount picture, The Caddy. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 14, 1991). — J.R.

SWAN LAKE — THE ZONE

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Yuri Illienko

Written by Sergei Paradjanov and Illienko

With Victor Solovyov, Liudmyla Yefymenko, Maya Bulhakova, Pylyp Illienko, and Victor Demertash.

One of the most fascinating things about Russian cinema is that we still know next to nothing about it. There are the socialist realist holdovers (Little Vera, for example, and Freeze — Die — Come to Life) and wannabe American releases (Taxi Blues), but the rest of the recent Soviet pictures that have made it to Chicago are interesting mostly because of what remains obscure and intractable about them — their refreshingly and, at times, bewilderingly different views of life and art.

The films that constitute the most obvious reference points in Soviet film history — a few key classics by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Vertov, and closer to the present, the films of Paradjanov and Tarkovsky — have practically nothing to do with what ordinary Soviet moviegoers see most of the time. Even worse, we can’t take it for granted that these avant-garde works necessarily represent the best that innovative Soviet cinema has to offer, or that what we see of the Soviet mainstream is necessarily the best either. Read more