Written for my En movimiento column for the September 2013 issue of Caiman Cuadernos de Cine. Reseeing The Hanging Tree tonight, I was fascinated to discover how much McCabe and Mrs Miller was indebted to its prostitutes and its fires, and how often Daves could use a crane as if it were a musical instrument.— J.R.

“Many of Delmer Daves’s films are beloved, but to say that he remains a misunderstood and insufficiently appreciated figure in the history of American movies is a rank understatement.” This is how critic Kent Jones begins the second of his two essays accompanying the simultaneous Criterion releases on DVD and Blu-Ray of Jubal (1956) and 3:10 to Yuma (1957), the first two in a string of three Westerns that Daves made with Glenn Ford. (The third was Cowboy in 1958.)

I saw the two Blu-Rays, in reverse order, on the same day, and I agree entirely with Jones that 3:10 to Yuma (ignoring its reportedly lamentable recent remake) is a remarkable achievement — as much for Glenn Ford’s performance as a charismatic villain as it is for the diverse dramatic and visual nuances of Daves, working in black and white and widescreen. Speaking as someone for whom Glenn Ford’s heroism in my youth was as important as that of James Stewart or Cary Grant, I was also astonished by the unpredictable and multileveled killer-hipster and delicate gangleader-womanizer he creates here (and also grateful for a fascinating interview with his son and biographer Peter Ford, included as a bonus). Read more

I’m thrilled that my favorite academic film critic, James Naremore, finally brought out a collection of his critical and theoretical essays, and even more thrilled that its final section, “In Defense of Criticism,” includes an essay on me (along with essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, and Andrew Sarris, and extracts from Jim’s own ten-best columns for Film Quarterly between 2007 and 2010). Naremore’s essay about me ends with an email interview, and Jim has given me permission to reprint that text here. You can order his book, An Invention without a Future: Essays on Cinema — which also contains some wonderful material about Hawks, Hitchcock, Huston, Kubrick, Minnelli, and Welles, as well as about such topics as acting, auteurism, and literary adaptation — on Amazon. — J.R.

I took advantage of my friendship with Jonathan Rosenbaum to interview him on e-mail about the practical concerns or realpolitik of working as a film reviewer. His replies give us insight into at least one corner of the world of critical journalism:

JN: As a weekly film reviewer for the Chicago Reader, were you given the word length you needed for reviews? Was there any pressure, however subtle, to review big commercial films over art films and revivals? Read more

The following was written in February 2009 for a projected volume on Stanley Kubrick that was being prepared at the time by the Chicago-based magazine Stop Smiling, which commissioned this and a few shorter pieces by me for it, including a short “sidebar” text about James Naremore’s On Kubrick, written in April 2010, which I’ve appended to our exchange. [2023: An expanded second edition of this valuable book has recently appeared.] For a variety of reasons, including the discontinuation of the magazine, the book never appeared, and the editor, James Hughes, gave me permission to post it here, originally in September 2013….I obviously guessed wrong when I surmised here that Kubrick’s family would probably keep Fear and Desire “off the market”. — J.R.

Early Kubrick: An Exchange

By Jonathan Rosenbaum and James Naremore

Dear Jim,

As you note in your book on Kubrick, he removed his first feature, Fear and Desire (1953), from circulation at some point during the 60s. I know this couldn’t have been during the early 60s because I saw it for the first time in 1961 or ‘62, at the Charles Theater, a legendary, eclectic arthouse on the Lower East Side, when I was a freshman at NYU. Read more

Reprinted from my 2007 collection Discovering Orson Welles, but with illustrations added. (The first of these is a photo taken near Antibes, France, where the revamped Touch of Evil was scheduled to premiere, until Beatrice Welles threatened a lawsuit and halted the screening. Much later, she sent a letter of apology to Janet Leigh that I got to read at one point. Fortunately, this didn’t prevent me from enjoying a wonderful day with Janet Leigh, her daughter Kelly, and several others on the Côte d’Azur, capped by this photo of the Touch of Evil re-edit “crew” and then followed by a memorable dinner.)

The following —- an account of my work as consultant for Universal Pictures on the re-editing of Touch of Evil in 1997-98, based on a studio memo -— is the only thing I’ve ever written for Premiere. I knew one of the editors, Anne Thompson, from her previous stint as assistant editor at Film Comment, and when I proposed this piece to her, she checked with other editors at the magazine and reported back that there was a lot of enthusiastic interest. When I asked her what approach I should take, she urged me to write a first-person account of my experience of the project from beginning to end, which yielded a first version. Read more

A slightly edited version of this article entitled “Devotional Reading” appeared in the November-December 2012 issue of Film Comment. For whatever it’s worth, I find Geoff Dyer’s taped interview about Stalker on Criterion’s Blu-Ray more perceptive than anything in this book. I guess he’s had more time to think about it by now. — J.R.

There are at least two intriguing recent trends reflected in the publications of Geoff Dyer’s Zona: A Book about a Film about a Journey to a Room (New York: Pantheon, 2012) and Adam Mars-Jones’s Noriko Smiling (London: Notting Hill Editions, 2011) — book-length studies of masterpieces (Stalker and Late Spring, respectively) and film criticism by amateurs (both of them prestigious literary Brits). A couple of much older attitudes underlying both is a view of cinema as literature by another means and, conversely, a view of film analysis as a literary and linear pursuit.

It’s obvious that what links these two trends historically is the phenomenon of home viewing, which has made every viewer a potential “expert” for the first time. Prior to VCRs and DVD and Blu-Ray players, the only tools available for studying films at length were 16 mm projectors and moviolas, most often belonging only to “professionals” of one kind or another. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 2002). I’m delighted to be posting this around the same time that Godard spoke with reverence about this film in a lengthy taped interview just posted on Facebook. — J.R.

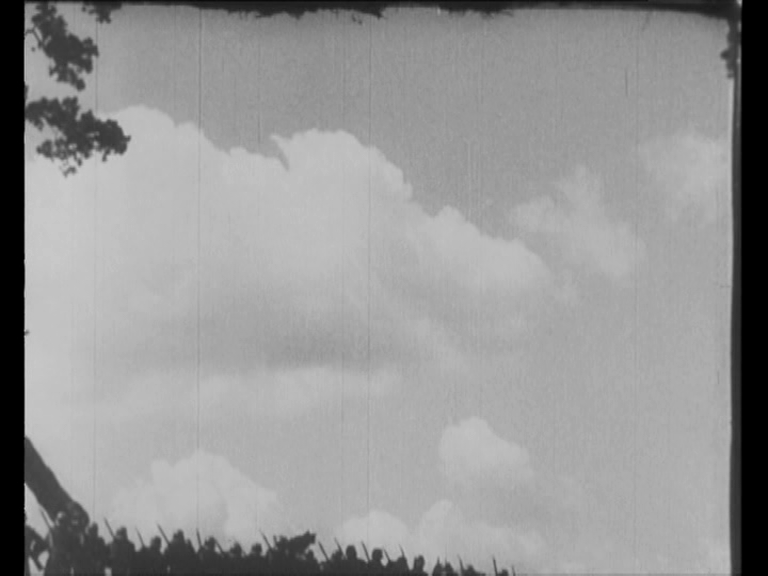

Earth (1930) is the most famous of Alexander Dovzhenko’s masterpieces, but this white-hot war film, made the previous year and screening only once in the Gene Siskel Film Center’s invaluable Dovzhenko retrospective, is in many ways his most dazzling silent picture. Though it was commissioned to glorify the 1918 struggle of Bolshevik workers at a Kiev munitions factory against White Russian troops, Dovzhenko’s view of wartime and battlefront morality is too ambiguous and multilayered to fit comfortably within any propaganda scheme. More clearly influenced by Sergei Eisenstein than any of Dovzhenko’s other pictures, it’s certainly the one that uses fast editing in the most exciting fashion, and some of the poetic uses of Ukrainian folklore that were Dovzhenko’s specialty have an almost drunken abandon here — as in the singing horses. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1978 (Vol. 45, No. 529). If memory serves, this was the last review I ever wrote for MFB, done on a trip back to London after I had moved to San Diego, although I believe I may have written a few features for the magazine after this, following its change of design and format somewhat later. (Postscript: This time, I’m afraid, my memory didn’t serve. I’ve just come across two more reviews I published in the MFB in 1984.) –- J.R.

White Buffalo, The

U.S.A., 1977Director: J. Lee Thompson

Cert–AA. dist–EMI. p.c–Dino De Laurentiis Corporation. p–Pancho Kohner. p. co-ordinator–Virginia Cook. p. manager–Hal Klein. location manager–R. Anthony Brown. asst. d–Jack Aldrvorth, Pat Kehoe. sc— Richard Sale. Based on his own novel. ph–Paul Lohmann. col–Technicolor; prints by Deluxe. process co-ordinator–Bill Hansard. ed—Michael F. Anderson. assoc. ed–Terence Anderson. p. designer–Tambi Larsen. set dec–James Berkey. sp. effects–Richard M. Parker. production sp. effects–Roy Downey. m/m.d–John Barry. cost–Eric Seelig. set cost— Dennis Fill. make-up–Phil Rhodes, Michael Hancock. titles–Dan Perri. sd. rec–Harlan Riggs. sd. re-rec–William McCaughey, Lyle J. Read more

Written for The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the

U.S., a catalogue/collection put together to accompany a film series at the

Austrian Filmmuseum and the Viennale in Autumn 2009. — J.R.

Long before the advent of Slavoj Zizek, U.S.

academic Joan Braderman in 1986 offered a bracing

exercise in standup theory and comic deconstruction

in this half-hour unpacking on video of the most successful

nighttime soap opera on television, which is

said to be the favorite series of one hundred million

people in 78 countries. Utilizing some of the special

effects of codirector and coeditor Manuel De Landa

to project herself literally into Dynasty and thereby

critique its cultural and ideological underpinnings,

Braderman manages to mix appreciation with scorn

in almost equal quantities.

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 2002). — J.R.

Alexander Dovzhenko’s first sound film, revolving around the construction of a giant dam on the Dnieper River, is one of his greatest, though it was poorly received in the Soviet Union when it came out in 1932. It’s only one of the eccentricities of this lyrical and monumental feature that the title refers to three different characters, and it’s telling that the father of one of them, an illiterate peasant who proudly spends his time fishing and loafing while everyone else works, is treated with considerable warmth. (A sequence in which he’s frightened when addressed by an outdoor loudspeaker evokes Chaplin as well as Tati.) As in all of Dovzhenko’s best work, the style veers closer to lyrical poetry (its opening sequence about the river) and portraiture (a later segment introducing us to various workers) than to narrative, though it’s innovative in other respects as well: the final sequence includes some striking jump cuts almost 30 years before Jean-Luc Godard purportedly invented them in Breathless. In Russian with subtitles. 90 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From American Film (July-August, 1981). -– J.R.

This summer, Manhattan’s Whitney Museum of American Art is honoring animation — the work of many unsung individuals at the Walt Disney Studio between the late twenties and early forties — as high art.

Guest curator Greg Ford has selected approximately fifteen’ hundred individual pieces of art from the immense Disney archives, ranging from individual drawings to about a hundred films. And the Whitney has taken t0he unprecedented step of commissioning SITE — an innovative architectural and environmental arts organization — to mount these heretofore hidden treasures.

Perhaps best known for its eccentrically designed showrooms for the Best Products Company, with crumbled, notched, peeling, and tilted façades, SITE promotes the concept of architecture as art rather than as design. By its own description, SITE “rejects the traditional concerns of architecture as form and space in favor of architecture as information and thought.”

According to SITE project director Theodore Adamstein, “We’re using the vocabulary of cinema to present this work.” Thus the whole second-floor gallery space of the Whitney is painted black, and lit by a silvery light that highlights the exhibits while keeping spectators in relative darkness. Forty twelve-by-eight-foot screenlike frames, used in a variety of ways, contribute equally to the idea of museum space as movie house. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 17, 2002). — J.R.

La Commune (Paris, 1871)

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Peter Watkins

Written by Watkins with Agathe Bluysen and contributions from the cast members.

Some filmmakers say this is my work and I want it to stay that way. That is their right, and we respect that right. Those are the films we don’t buy, and those are the films we don’t transmit. — TV executive in The Universal Clock: The Resistance of Peter Watkins

I’ve been a fan and supporter of Peter Watkins for most of my life. A remarkable master technician and social visionary whose early work is filled to the brim with focused rage, he has created some of the most troubling, thought-provoking, even shattering films I know. This has helped make him persona non grata in mainstream TV and cinema and also in art houses, among academics, at festivals, and on cable TV. When his name does come up in those diverse realms, he’s often accused of being paranoid — though that hardly explains his pariah status.

Keeping up with his work is hard even for a sympathetic critic like me, and I can’t say I know it well. Read more

From the Bard Observer (September 9, 1964). I ran the Friday night film series during most of my time at Bard College, and in many cases, I was booking these films in order to see them for the first time (although, as I recall, not in the cases of North by Northwest, Zazie, Jules and Jim, This Sporting Life, Freaks, or The Phenix City Story). –- J.R.

Sept. 12 KEY LARGO (See page 4 for a review.) [Note: this was a reprint of James Agee’s original review of this film in The Nation.]

Sept. 18 TROUBLE IN PARADISE. Continental comedy borne up out of the early thirties, directed by Ernst Lubitsch.

THE PASSION OFJOAN OF ARC. Mlle. Falconetti suffers in public and in silence. Directed by Carl Dreyer in 1928.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sept. 25SAWDUST ANDTINSEL Also known as “The Naked Night”. The only Ingmar Bergman film Bard can afford (also one of the best). A circus setting; made in 1953.

Also: “Jammin’ the Blues,” 10 minutes of Lester Young, Harry Edison, Jo Jones and others.

Oct. 2 FREAKS/THE PHENIX CITY STORY A double feature devoted to le film maudit: 2unconventional American “B” pictures—the first an unclassifiable and unsettling 60-minute story of sideshow life, the second a sensational “exposé” of corrupt Alabama politics, filmed on location. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (June 1, 2002). — J.R.

The first feature Alexander Dovzhenko made outside his native Ukraine (1935, 93 min.) takes place in a vast Siberian forest on the Pacific coast populated by religious villagers, hunters and adventurers, and Japanese spies, where the Soviets planned to establish an airfield and a city. Frankly operatic in its portraiture and poetic sylization, this Soviet masterpiece began as propaganda but veers closer to pagan fantasy than any of Dovzhenko’s other sound films, and it quickly became a favorite of both Elia Kazan and James Agee when it opened in the U.S. under the title Frontier. As always in Dovzhenko, the depictions of death are especially memorable. In Russian with subtitles. (JR)

Read more

Read more

The second part of my reprinting of Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980); this part appeared originally in Film Comment, and for this appearance I’ve added several illustrations.

Note: The book can be purchased on Amazon here, and accessed online in its entirety here. — J.R.

Prelude—

What I Did on My Summer Vacation (September 1977)

Imagination believes before knowing constructs. Believes longer than remembers, longer than knowing even conjures. Knows believes conjures a highway in Mississippi, August 10, on the way to Faulkner’s home in Oxford, tracing a literary pilgrimage from Florence, my hometown in Alabama, part of whose route might approximate the pregnant journey of Lena Grove on the opening pages of Light in August.

What has any of this to do with cinema? First, the car’s languid progress up and down a straight road flanked by forest: a trick of suspended time, pure movie and pure Faulkner. Then the hot moist afternoon light filtering through the branches into a milky pool of delicate focus, like the last scene in Carl Dreyer’s Gertrud, making it easy to imagine in a tactile, even in a carnal way why Dreyer wanted to adapt Light in August, thinking Yes of course only Dreyer could have done it right, handled both sides of the dialectic, all the hot wood and cold flesh and embracing palpitant air, impregnable and inviolate. Read more

R.I.P. Jonas Mekas, Patron-Saint of Cinema, 1922-2019. — J.R.

(from http://www.incite-online.net/jonasmekas.html)

Anti-100 Years of Cinema Manifesto

By Jonas Mekas

As you well know it was God who created this Earth and everything on it. And he thought it was all great. All painters and poets and musicians sang and celebrated the creation and that was all OK. But not for real. Something was missing. So about 100 years ago God decided to create the motion picture camera. And he did so. And then he created a filmmaker and said, “Now here is an instrument called the motion picture camera. Go and film and celebrate the beauty of the creation and the dreams of human spirit, and have fun with it.”

But the devil did not like that. So he placed a money bag in front of the camera and said to the filmmakers, ‘Why do you want to celebrate the beauty of the world and the spirit of it if you can make money with this instrument?” And, believe it or not, all the filmmakers ran after the money bag. The Lord realized he had made a mistake. So, some 25 years later, to correct his mistake, God created independent avant-garde filmmakers and said, “Here is the camera. Read more