From the November 11, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

*** OLEANNA

(A must-see)

Directed and written by David Mamet

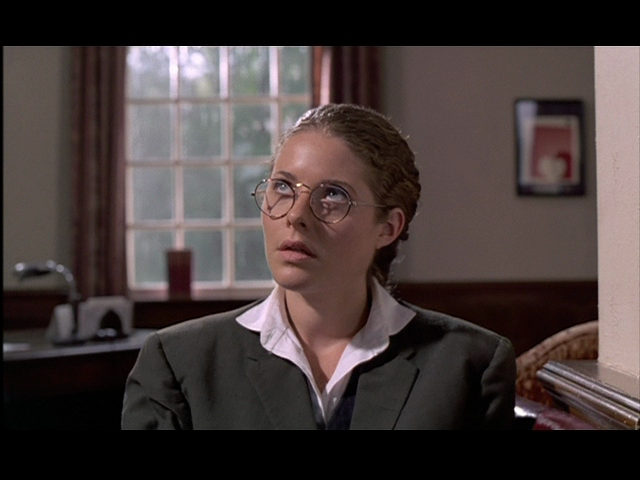

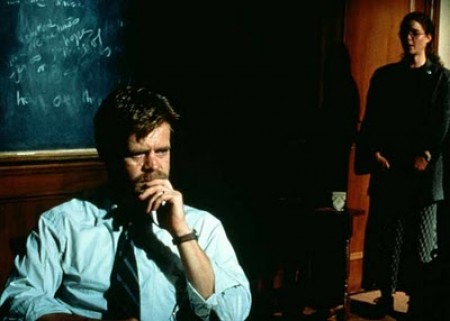

With William H. Macy and Debra Eisenstadt.

David Mamet’s four features to date, none of them realistic, are all concerned to a greater or lesser extent with con games. Ultimately what one thinks of any of them has a lot to do with which side of the con one winds up on — which proves to be a matter of how one relates to the style as well as the content. Language is the major instrument of both seduction and deception in these films, and Mamet’s stylized use of it, playing on its ellipses and ambiguities as well as its more abstract and musical qualities, often deceives and seduces the audience. So how one responds to these characters has a lot to do with how one reacts to these language games.

To my mind, House of Games and the first half of Things Change are seductive (if brittle) fantasies about the allure and danger of spinning seductive fantasies; the second half of Things Change and Homicide are outsized sentimental bluffs. All three films star Joe Mantegna, are about criminals, and bear some relation to Hollywood genres; but where one places one’s trust and emotional allegiances is different in each case.

Oleanna, the first of Mamet’s films to be based on one of his plays, does without Mantegna, criminals, and Hollywood genres. By and large, it’s simply a film of a play, with a modicum of added background material and filler. At first glance one might conclude that the world of this film is both realistic and uninformed by con games; the setting, after all, is a contemporary American university, and the only characters are a male professor up for tenure named John and a female student about half his age named Carol. But first impressions are nearly always false in Mamet’s world. As it turns out, the situations in the film are “real” but not realistically depicted, and con games are very much in evidence, though with a significant difference: this time the characters con themselves rather than each other.

A profound change took place in colleges in this country 20-odd years ago — in my case, between the time I attended college in the early 60s and when I started teaching in the late 70s. To put it in the blunt terms of my own middle-class experience and mythology, college in the early 60s was a utopian refuge and a way to escape the business of killing — literally in that there was the possibility of serving in Vietnam, figuratively in that entering the job market meant encountering the burdens and brutalities of capitalism (then as now, “making a killing” was viewed as the preferred goal of the society at large).

This notion had become more complicated by the time I landed in graduate school in the mid-60s, when many students’ lives were being taken over by radical demonstrations, but even then the concept of the academy as a “free zone” outside the mainstream of American life was operative. Yet by the time I returned to academia as a teacher this concept was effectively defunct. Ironically part of the change was the consequence of student reforms the earlier demonstrations had set in motion, but by then students were attending college less as an escape and more as a form of basic training — arming themselves for the marketplace “killing” to come (which they usually wanted to encounter as soon as possible).

Since the late 80s, when I left teaching for journalism, campus life has undergone another mutation, which might be described as a shift from basic training for combat in the outside world to armed combat on campus, with aspects of the academic institution itself employed as weapons by teachers, administrators, and students. The battles aren’t simply among these three academic “classes,” but within each of them as well. One can choose to see these battles as forms of the political and social battles being waged concurrently in the larger world (though they can also be regarded as shadow plays or sporting events), but the fact remains that these battles are often fought over symbols of values that are being disputed in the world outside rather than the values themselves. One reading of these feminist and multicultural debates might be that they point to a defeatist abnegation of the power of politics to change the world and opt instead for simply changing the permissible discourse about that world — for altering the labels and symbols for realities society as a whole has deemed unchangeable. To pursue my earlier analogy, it’s almost as if a video war game has replaced actual war, with the winners entitled and sometimes even expected to destroy the losers afterward.

Oleanna is a stark and effective depiction of the results of this third mutation — an academic world that can no longer be divided simply between perpetrators and victims, because everyone within this system takes on both roles. Mamet stages the central conflict between the sexes, between generations, and between classes, but he manages to make the conflict both personal and nonspecific: we’re never told what liberal-arts subject the professor teaches or what the student’s major and professional interests are, and when she speaks about the campus “group” she belongs to, no details about it are given. It’s implied that the student’s background is working class, but the professor’s class origins are never spelled out.

The dramatic conflict we’re shown is basically Strindbergian, and if this observation prompts the observation that Strindberg was a misogynist — a label often assigned to Mamet as well — it’s worth citing critic Richard Gilman on the subject of Strindberg’s misogyny: “We know . . . that Strindberg’s anti-feminism was in no sense political, that it was accompanied by a conviction, for which he publicly fought, that women had been the victims of legal injustice; in that sense he was at least as much a believer in women’s rights as Ibsen.”

Without getting into the issue of Mamet’s personal politics (as distinct from the political inflections of his work), about which I know little, it’s certainly true that he tends to write better and worse dialogue for men than for women — better in House of Games, where the lines of Mantegna’s character and those of his male coworkers tend to sing, while those of the protagonist (Lindsay Crouse) and her older female colleague are relatively nonmusical and nonpoetic; worse in Homicide, where the macho posturing of the male dialogue becomes as freakishly manneristic as the worst of late Hemingway.

In Oleanna, John is a more believable, better-fleshed-out character than Carol, perhaps because his stances are more familiar. Many viewers have concluded from this that the play is more on his side than hers, and Mamet’s epigraph for the play — a quote from Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh about the adaptability and self-deceptions of the young — seems to bear this out. Not having seen any of the play’s stage productions (though I’ve read the script), I can only report secondhand impressions, but it appears that Mamet benefited from some of the feminist critiques of the play, making the antagonists in the film more evenly matched. Doubtless other differences stem from the role of Carol being taken over by Debra Eisenstadt, who was the understudy for Rebecca Pidgeon (Mamet’s wife) in the New York production but played the part during the play’s national tour. (William H. Macy, who plays John, has been involved with the play since its inception and even directed it in Los Angeles; he’s also had successively bigger roles in Mamet’s films — as an army sergeant in House of Games, a Mafia lackey in Things Change, and Mantegna’s police partner in Homicide.)

Still, how one responds to the film is so much a matter of one’s subjective investment in the issues that no two people can come away with the same impression. To my mind, both characters come across as equally odious and equally tragic — so much so that one can see them only as different generational and gender-specific expressions of the same character flaws and the same perverse will to power, even though John emerges as more comprehensible than Carol. Viewed simply as a sporting event, Oleanna remains, to coin a term, more than a little machocentric. But viewed as a dramatic conflict objectifying something real that’s taking place in our culture beyond individual allegiances and biases, the film is considerably more than that — it’s a dispassionate analysis of a political warfare that’s currently tearing our country asunder. Within this context winning or losing battles becomes far less significant than the violence done to character, language, and morality in the course of waging those battles — an analysis that could easily be applied to recent election campaigns.

Mamet — who says he wrote the play before the Anita Hill-Clarence Thomas hearings and pulled it out of his drawer only afterward, when he decided, “This play isn’t as farfetched as I imagined” — reports that the play’s first audiences tended to react violently: “People used to get into fistfights in the lobby. And couples who came on a date would leave screaming at each other in different taxicabs. It happened night after night.” Insofar as symbolic forms of warfare, including sports, are usually taken more seriously in this country than artworks, and tend to generate much deeper emotions, this is a perfectly understandable response but not an especially helpful one.

Since the importance of this work seems more a matter of interpretation than of plot development — how things happen rather than what happens — and more a matter of analysis than of choosing sides, I assume I can talk about the plot here without “giving away” anything essential. Readers who don’t want anything given away are invited to check out now.

The action of Oleanna transpires in John’s office over three acts, the first of which is much longer than the other two. In the first act, John is in the process of settling a deal on the phone to purchase a house; he’s also on the verge of receiving tenure. Carol comes to ask him about a low grade she’s received on an exam paper and is clearly concerned about flunking the course. Constantly interrupting her when he isn’t being interrupted by phone calls, he proceeds to belittle a sentence in her paper about his book — the assigned classroom text — which she tells him she doesn’t understand. He then launches into a speech about the overall silliness and arbitrariness of formal education, patronizingly assures her he fully understands her confusion and her low self-esteem, which he used to have himself, says he likes her, and proposes giving her an A in the course if they can schedule further meetings.

By the second act, set some time later, the power balance between the two has already shifted. John has been denied tenure because of a complaint filed by Carol with the tenure committee about the sexism, racism, patriarchal self-aggrandizement, and sexual overtures to her that she claims he was guilty of in the previous scene. This time Carol is able to finish more of her sentences (despite additional phone interruptions), and she derides him for his contempt for education; John tends to be on the defensive, though the conversation is again dominated by incomplete phrases whose meanings are often ambiguous. Hoping to get her to withdraw her charges, he succeeds only in alienating her further. He briefly restrains her when she tries to leave the office, which leads her to break away and call for help.

By the third act the charges against John, supported by a group Carol belongs to, have grown so serious that he’s been dismissed from his job. This time it’s mainly she who delivers the speeches, denouncing him at length, and he who meekly listens. (An interesting touch: Carol’s dress becomes more traditionally “feminine” in each scene, starting off with blue jeans and winding up with a long skirt.) She suggests her group will withdraw the charges if he agrees to eliminate several books from the college curriculum, including his own; he indignantly refuses. Then he discovers that she’s contacted a lawyer and filed charges of attempted battery and rape against him because he restrained her. He tells Carol he hasn’t been home for two days — we’ve already seen him briefly in a hotel room — and her departure is interrupted by a phone call from someone he addresses as “baby”; whether this is his wife or a mistress remains pointedly unclarified. Carol says, “Don’t call your wife ‘baby,'” a parting shot that goads John into beating her up and threatening her with further violence. After John is mortified by his brutality — “Oh, my God,” he says — and Carol replies, “Yes, that’s right,” the play ends.

Not so much a battle of ideas as a power struggle in which both parties use the academic institution as a blunt instrument for empowerment, intimidation, and injury, Oleanna can be viewed as a withering critique of what that institution has become — a totalitarian hell in which two forms of authoritarianism vie for supremacy. In different ways John and Carol are warped children of the 60s — he with his hypocritical contempt for the rituals of formal education that grant him the authority to pontificate, she with her uncritical faith in the same practices, which ultimately grant her the authority to retaliate. The fact that both characters feel powerless to overthrow or reject this system, which grants them the only power they can wield and the only identity they can call their own, calls to mind the perverse vendettas carried out by Russian bureaucrats (not to mention artists) against one another during the Stalinist period. Within such a context “education” becomes as much a rationalization for self-empowerment as “political correctness”; both become desperate substitutions for politics, not to mention other forms of self-identification and self-fulfillment. (Audience members who identify either character exclusively with the left are surely missing the point; as spokesmen from Rush Limbaugh to Forrest Gump demonstrate, neither mockery of institutions nor PC restrictions are the property of any political persuasion.)

It might be argued that Mamet isn’t concerned so much with politics or psychology as with the inadequacies of the language people speak, yet his portrait of that language has too many ugly political and psychological ramifications to ignore — unless one insists on ignoring them with the same vehemence that the characters do. If both characters are somehow children of the 60s, there is also a generation gap: John is identified with the failed radicalism of the 60s, which explains his compulsive mockery of a system his generation once hoped to overthrow, and Carol is identified with the failed neoconservatism and puritanism of the 80s, which explains her own totalitarian compulsion to eliminate any skepticism about that system that lingers. Because each character is capable of hearing only confirmations of or challenges to her or his own agenda in the other’s words, and neither can postulate an identity apart from academia as it’s constituted, both are condemned to remain inside a treadmill of mutual abuse, perpetually completing or misreading each other’s sentences. Just like the Democrats and Republicans.