From the Chicago Reader (June 2, 1995). This piece is quite separate from the essay I contributed to Criterion’s DVD of this film 15 years later. — J.R,

Crumb

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed by Terry Zwigoff

Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb in many ways looks like conventional filmmaking, yet it conveys a remarkable fluidity and density of thought. It may resemble a biographical documentary — unobtrusively shot by Maryse Alberti, gracefully edited by Victor Livingston — but it unfurls like a passionate personal essay. The subject is Robert Crumb, America’s greatest underground comic book artist — little known to most people born much before or after 1943, the year of his birth, because he’s shunned the mainstream as a money-grubbing swamp. Zwigoff, an old friend, shot the movie over six years and edited it over three, and the sheer mass of this two-hour film seems partly a function of the amount of time he’s had to mull it over.

A member of Crumb’s former band, the Cheap Suit Serenaders, and a fellow collector of rare 20s and 30s blues and jazz records, Zwigoff has previously made documentaries only on musical subjects — blues artist Howard Armstrong in Louie Bluie, a history of Hawaiian music in A Family Named Moe. He noted in one interview that he was in therapy while shooting Crumb, a fact that’s surely left its mark on the material. Clearly Zwigoff sees Crumb as an artist, not just a comic book artist, and his multifaceted approach to this biographical terrain has all the elegance of three-dimensional chess: he crosscuts effortlessly between Crumb with his two brothers on opposite coasts and Crumb ruminating over his work at home and leapfrogs between Crumb’s first wife, son, two former lovers, and various colleagues and commentators. Crumb’s life is thorny and depressing as well as fascinating, and Zwigoff’s approach is unusually serious and methodical: just about everything that’s said about Crumb is intelligent and seems to have been included because Zwigoff agrees with it on some level.

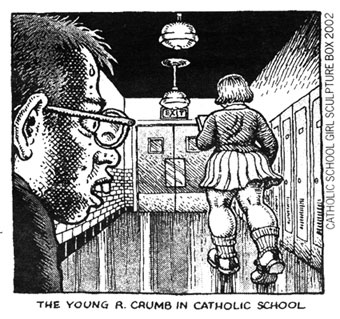

But despite the film’s clear and purposeful editing, the issues Zwigoff raises are complicated, disparate yet interrelated, big questions that torment the mind and heart — which may be one reason reviewers have had a rough time describing Crumb. What does it mean to be an American artist? What are the differences between satire and pornography, confession and entertainment, art and obsession, sanity and schizophrenia? What does it mean to have and be a brother, especially growing up in a brutally dysfunctional Catholic family — ruled by a violent father (he busted Robert’s collarbone when he was five) and by a mother addicted to amphetamines, a family whose three brothers slept together in the same bed until their teens? (Crumb’s two sisters declined to appear in the film, and it isn’t too hard to figure out why.) Even the movie’s title begins to seem metaphorical: one thinks of a crumb in the all-American cake, a slender morsel of American pie in the sky.

The vexing questions keep coming, questions like what the true legacy of the 60s counterculture is. And has there been a decline in the quality of American life since the 1920s, as Crumb sorrowfully claims when we see him moving to France in 1993? Are most artists, including confessional ones, innocent of the meaning and impact of their own work? Can art making function as a bulwark against madness? What are the crucial differences between art, which is personal, and impersonal business franchises — especially in a society that so plainly values the latter over the former? And finally, what is the significance of sniggering?

Let’s start with the sniggering, which we hear whenever Robert gets together with his older brother Charles (still living with their mother and unemployed since 1969) or his younger brother Maxon (living alone in a San Francisco flophouse, meditating two hours daily on a bed of nails). Both of his brothers are also exceptionally gifted, self-aware artists, but unlike Robert they’re misfits who never climbed out of obscurity and often wound up institutionalized, on medication, or both. Most of what’s memorable about Crumb has to do with these brothers; by the time the film is over, one is fully persuaded that if Robert weren’t drawing constantly and compulsively he’d be every bit as doomed as they are. (Referring to these people as if they were fictional characters makes me uncomfortable, but the film’s careful establishment of their personalities makes it hard to do otherwise; whether Zwigoff intends this or not, they become characters within the context of the film.)

The terrible yet familiar laughter Robert shares with his brothers reveals a kind of tortured complicity in sexual obsession: as a five- or six-year-old kid Robert was sexually drawn to Bugs Bunny; Charles as an older kid was secretly preoccupied with Hollywood boy actor Bobby Driscoll; and Max in his late teens — the most sexually repressed of them all and subject to epileptic fits — became a molester of women. He describes stalking a woman on the streets of San Francisco and pulling down her shorts with a curious mixture of horror and relish. The fact that each brother is fully aware of his obsessions and even lucid about them only heightens their shared amusement, which sounds unnervingly like ordinary locker-room repartee, enchanted with its own gross-out dementia.

Every American male knows the sound of that nervous tittering, and Robert Crumb’s comic world is not only suffused with it (his own adult sexual obsession is amazonian, big-assed, thick-legged women) but encircled by it. I can’t think of any other movie that’s dealt with this kind of laughter so directly. Cassavetes’s fictional film Faces probably came the closest, but there it was simply backslapping businessmen dealing with everyday sexual embarrassment. Crumb cuts deeper, letting us see the potential madness lurking beyond the simple nervousness of sexual panic — a madness disquietingly made to seem as American and almost as ordinary as that pie in the sky. This is one creepy movie, and it should come as no surprise that David Lynch, who helped to get it released, is mentioned at the top of the credits.

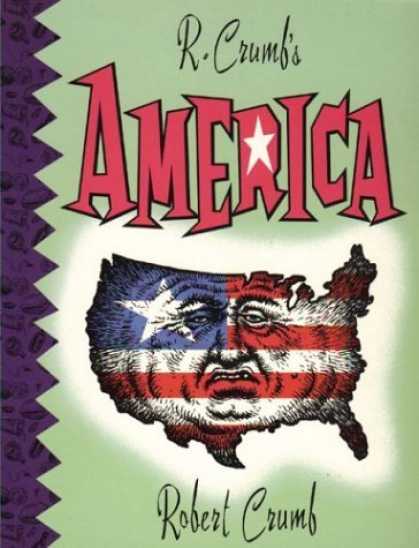

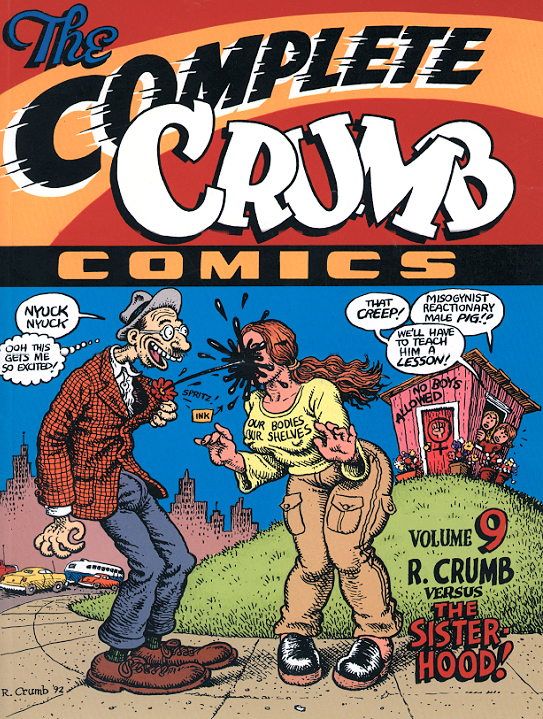

There are few artists as compulsively and relentlessly confessional as Robert Crumb, so in some respects Crumb functions simply as exegesis of and critical commentary on three and a half decades of published work. Since I first encountered Zwigoff’s haunting masterpiece last summer I’ve been reacquainting myself with Crumb’s work and catching up with things I’d missed, and it’s remarkable how consistent most of it is. (For a provocative overview, I’d recommend R. Crumb’s America.) Of the ten volumes of The Complete Crumb Comics (which don’t include several sketchbooks and collections like R. Crumb’s America, though all include biographical or autobiographical introductions), perhaps the first three qualify as apprentice work. But after that Crumb’s graphic style and view of the world are fully formed. Apart from the occasional collaboration or commission, what mainly changes in his work is the degree of explicit self-reference — the extent to which Crumb himself supplants his characters. And the movie, by providing a detailed context, helps to unpack many references that were previously obscure.

Case in point: The first time I read XYZ Comics, back in 1972, I didn’t even notice that a strange and unfunny story called “Nut Factory Blues” was signed “C. & R. Crumb” — coauthored by Charles and Robert in a variation on their joint childhood efforts, with each brother drawing and writing the text for his own character. Clearly all the drawing in “Nut Factory Blues” is by Robert, but as he explains in his introduction to volume nine of The Complete Crumb Comics, much of the dialogue derives from a conversation with Charles at a mental institution in Philadelphia in 1972, and the characters standing in for the brothers — Fuzzy the Bunny and Donnie Dog — were Charles’s childhood inventions. (The story’s title derives from a 1931 blues record.)

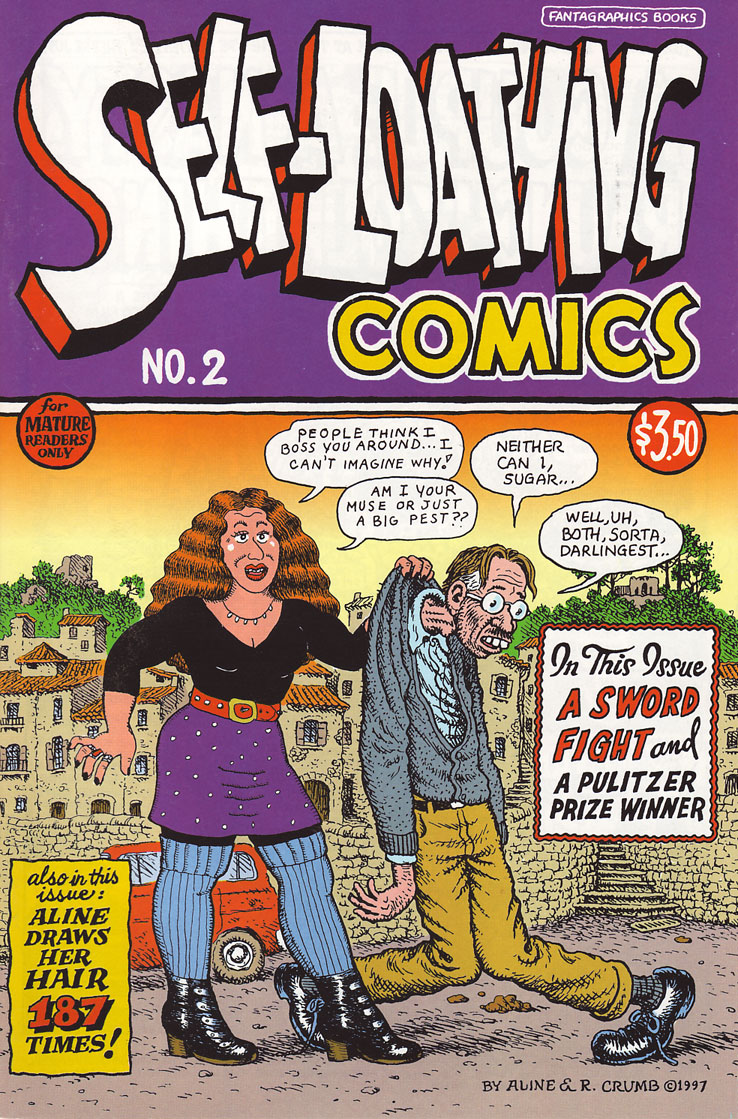

In recent years Crumb has separated himself even further from the American mainstream. His collaborations have been with his wife, cartoonist Aline Kominsky. Their daughter Sophie was born in 1981, and in 1993 he traded six of his sketchbooks for a house in the south of France and moved there with his family, an event chronicled in detail at the end of Crumb. Earlier this year Self-Loathing Comics appeared, in which each spouse separately recounts the banal daily routines of their life in France, with the two stories fusing in a single panel on the comic book’s center pages. The April 24 issue of the New Yorker carried a two-page comic strip in which the couple recorded their responses to seeing Crumb on video, each drawing her or his own character and furnishing the appropriate dialogue within shared panels. (Aline: “I just read in Newsweek that the Academy Awards judges turned off Crumb after 25 minutes.” Bob: “Yeah? Good! If they’d loved it can you imagine the hell our lives would become?”)

Crumb’s recent productions show a healthy contempt for merchandising, indeed for any effort to gain public approval or notice. Two decades ago Crumb decided to kill off Fritz the Cat after he was made the star of two animated features against Crumb’s will and without his control, and his anger about this and other misappropriations points to an artisanal pride in his work in direct opposition to the ambition he’s expected to have in a culture that equates quality with quantity. At the same time, his shrinking subject matter and expatriate status suggest that he’s backed himself into a corner; without America or his flaky cast of characters to keep his comics going, he’s seemingly milked his own persona dry. Yet part of what Crumb shows us is that a move so potentially debilitating to his art may have been psychically necessary.

I’ve never met Robert Crumb, but he served as my guide the first time I took LSD, in 1968, when we were both 25. Significantly, that encounter involved fraternal complicity as well as fraternal betrayal, a subject that’s at the center of Zwigoff’s movie. Both Robert and Max at times can barely suppress their rage toward Charles, nor can Charles suppress his toward Robert; this movie is as much about fraternal conflict as it is about Charles’s impact on Robert and Max. Though the movie doesn’t spell out all the family dynamics, it still offers plenty: an “amazonian” mother who takes amphetamines to lose weight in order to please her exacting husband, a trio of sons who invent a world of their own to escape the same tyrant.

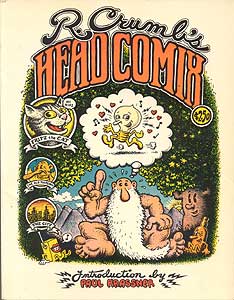

My younger brother Michael, who’d already dropped acid several times and was supposed to be my guide, failed to turn up at my Greenwich Village flat. We’d dropped our matching tabs while speaking on the phone that afternoon, then he boarded the downtown subway to my apartment. But he got lost, and I didn’t see him until the next day. Fearful of being alone, I turned to R. Crumb’s Head Comix — the first mainstream Crumb collection, which I’d just bought — for company, guidance, and edification. Considering that Crumb ascribes much of the freedom of his work (not only his subject matter but his approach to narrative) to his first acid trip in 1965, an experience that unleashed most of the characters and visual concepts he’s known for today, he wasn’t a bad choice. I’m sure I could have done much worse — indeed, did do much worse when I ventured out a few hours later to see Barbarella, a much more corrupt, strictly mercantile package of 60s zeitgeist.

The point is, even a screwball like Crumb had more workaday wisdom to get me through the night than most of what the rest of the culture was offering — or still has to offer, for that matter. Crumb may have been nuts, but he wasn’t a fool: he fully understood that his own preoccupations coincided with those of the counterculture. And there was something oddly sane as well as enriching about his vision of the freak-out period we were both living through; as Crumb shows, he was always somewhat detached from it, as he is from humanity in general. My brother might well have made my trip easier, but Crumb made it a lot funnier.

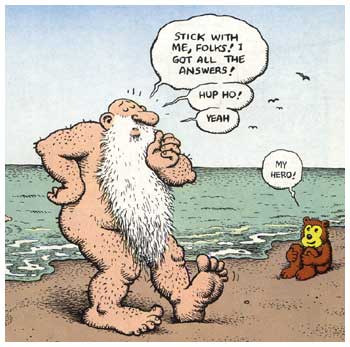

His art saved me from a bad trip, no small accomplishment. Beginning with an introductory page that presented Crumb himself in the role of a mad scientist, Head Comix featured numerous free-form trips to instruct and interact with my own. The cast of characters included Fritz the Cat, the dancing dudes of “Keep On Truckin’,” Schuman the Human (“Better known as ‘Baldy’ he goes forth with his fine mind to find God!” reads the opening caption. “And believe me, he took along a lunch!”), Mr. Natural (most likely based on Max, today a Hindu), Flakey Foont, Whiteman (a portrait of Robert’s uptight father, as we learn from Crumb), Western Man (alias President Lyndon B. Johnson), the Old Pooperoo, Kitchen Kut-Outs (including Clever Mr. Ketchup, Sammy Saucer, and Beatrice Bread Slice, the latter named after Crumb’s mother), and finally Angelfood McSpade, a naked African woman Crumb hadn’t yet gotten around to naming at that stage in his career.

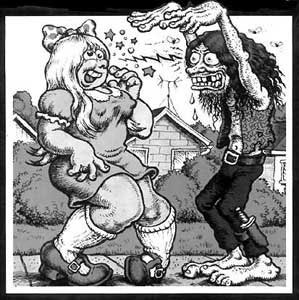

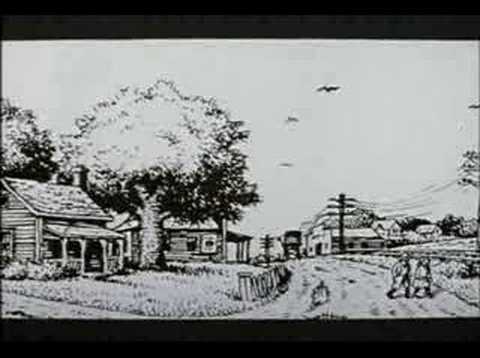

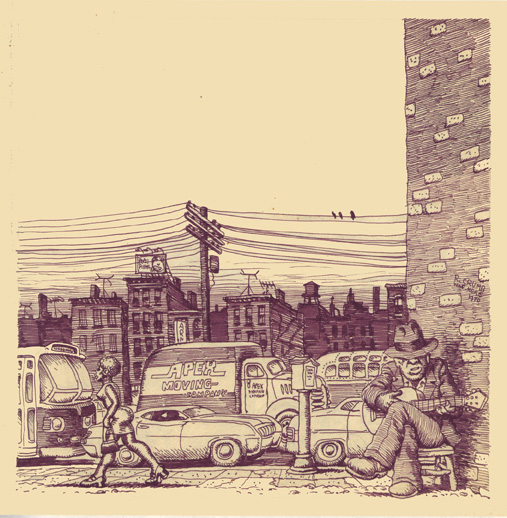

Then as now his grossly stereotypical characters revealed the underside of a world I already knew, a world that grew in part out of old ads, animated cartoons, and furniture displays — an archetypal past America, strictly working-class, urban, and comfortably squalid, populated by a community of goofy amblers and dim-witted, wiseass layabouts. (Crumb’s huge collection of 78s, his old-fashioned hats and bow ties, and the Cheap Suit Serenaders are only some of the more obvious manifestations of this world outside his comic books.) Superimposed on this quaint, idyllic world — and oddly coexisting with it — were enormous quantities of lust, cruelty, violence, fear, resentment, loneliness, anxiety, spiritual desperation, and the sniggering laughter alluded to. Crumb superimposed on a warm and wistful view of the 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s a surreal, highly satirical view of the present; conjuring up a jostling street life of adolescent epithets, infantile games, and adult concerns, Crumb’s art fully justifies critic Robert Hughes’s description of him (in Crumb) as “the Bruegel of the last half of the 20th century,” who offers us “lusting, suffering, crazed humanity in all sorts of bizarre, gargoylelike allegorical forms.” Hughes adds that “there wasn’t a Bruegel of the first half” — yet ironically the first half of this century was the source of most of Crumb’s scenic backgrounds.

The Bruegel-esque Crumb is an ironic observer and social chronicler, and if that’s all his art consisted of Crumb wouldn’t be nearly so disturbing. But then there’s Crumb the asocial narcissist and devoted nose picker, tireless explorer and exploiter of his own inner demons — closer to Hieronymus Bosch than to Pieter Bruegel — fueled by self-absorbed pornographic fantasies, bent on creating images for masturbation, and getting some of his rocks off by celebrating gratuitous violence, much of it against women. (One feels sure that Crumb himself can’t always tell whether these episodes critique or celebrate violence, and wonders how much acid he actually took back in the 60s and 70s.) His wife defends this work, however, as an expression of pure id that has nothing to do with what her husband is really like (“He gets it out in his artwork”).

Crumb himself is plainly ambivalent: he doesn’t like to censor himself, but he’s not always persuaded that what he does is socially defensible, and often he’s as befuddled as we are about the meaning of the work. If one could only separate the social Crumb from the asocial Crumb, the task of assessing his work would be a lot easier. But in fact these two sides of his character overlap and blur in a manner that seems quintessentially American; his art breaks down the same barriers between self and society, between fantasy and reality, that hallucinogenic drugs like LSD were intended to remove. And an unreconstructed rebel like Crumb never bothered to reinstate those barriers. His art, which combines the caricature of Hogarth with the lyrical self-diddling of Genet, is a dangerous, volatile mixture that eludes a precise moral agenda and any ordinary social use.

Two 1993 items included in R. Crumb’s America, “When the Niggers Take Over America” and “When the Goddam Jews Take Over America,” both clearly meant to ridicule racist paranoia, have reportedly been appropriated by neo-Nazi skinheads in the United States and Europe, all of whom are presumably too stupid to realize that they’re the intended targets. It would be comforting to report that these items are hilarious and dead-on; in fact they’re plodding, obvious, and unfunny. But even if one rejects these two strips as misfires, there are plenty of others in the Crumb canon that rest uneasily between self-indulgent fantasies and grim commentaries on the ideologies they purport to criticize. Consider “A Bitchin’ Bod,'” a morbid story Crumb started about a headless woman Mr. Natural presents to Flakey Foont as a literal sex toy. He set the strip aside, he says in Crumb, until his wife persuaded him to complete it despite his reservations. It hardly qualifies as uninflected pornography, but whether such a sicko fantasy overwhelms any commentary Crumb might make on it remains an open question.

Crumb recounts a story in the introduction to the ninth volume of The Complete Crumb Comics that starkly illustrates the conflict between his artistic and ethical reflexes. Zwigoff, horrified by a visit to a slaughterhouse, decided to publish a comic book inveighing against cruelty to animals and convinced various artists, including Crumb, to contribute stories. Crumb’s offering in the 1972 Funny Animals is the two-part “What a World” — and as Crumb freely admits, it was “one of the sickest, most violent, bloody, nihilistic as well as sadistic, misogynist things I’d ever drawn.” Crumb’s story and some of the others submitted led Zwigoff to dissociate himself completely from the book before it appeared. Obviously his friendship with Crumb survived this rift — and Crumb makes no allusion to the incident — but it’s notable that, even given a cause he himself deemed “noble,” Crumb still indulged the demonic side of his art.

Much of Crumb‘s soul and intelligence derives from the determination to confront problems of this sort and own up to their complex ramifications, not to let either Crumb’s work or its detractors off the hook. The movie’s refusal to settle for one Crumb or the other as a substitute for the whole artist is really a decision to take art seriously rather than regard it as an adjunct to other enterprises, as usually happens in this culture. Ultimately, one feels that Crumb’s work is being defended rather than attacked. But the film also leaves the impression that art — like life, and unlike entertainment — isn’t a picnic in the park.

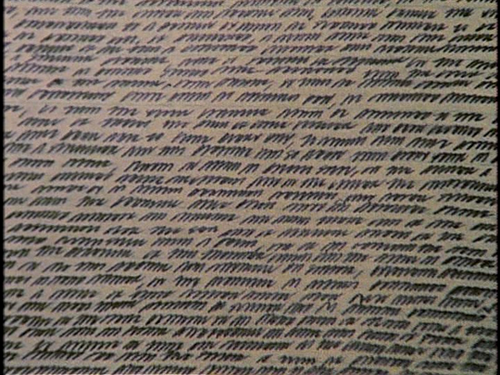

On one level the movie is an inspirational story about how a sensitive, nerdy person with a traumatic childhood can turn that misery into some form of art. But then there’s the story of Charles, the older and originally more gifted brother — the bullying guru who got Robert and Max started as artists. Zwigoff gives us an opportunity to look over Charles’s shoulder into an abyss. We learn that, before he stopped producing his homemade comics in 1961, he got more and more into dialogue and less and less into drawing. We see the evolving results as Robert flips through the pages of Charles’s work — words crowding out pictures, then pages and pages of just words followed by even more pages, seemingly hundreds of pages, covered with tortured, intricate scratches that are no longer words, that are no longer anything but scratches. It’s the most terrifying image in any movie I’ve seen this year, a steady, mocking bass line throbbing behind everything positive and exalting this film has to say about the power of art to transform suffering.