From the Chicago Reader (March 9, 2006). — J.R.

Moments Choisis des Histoire(s) du Cinéma

**** (Masterpiece)

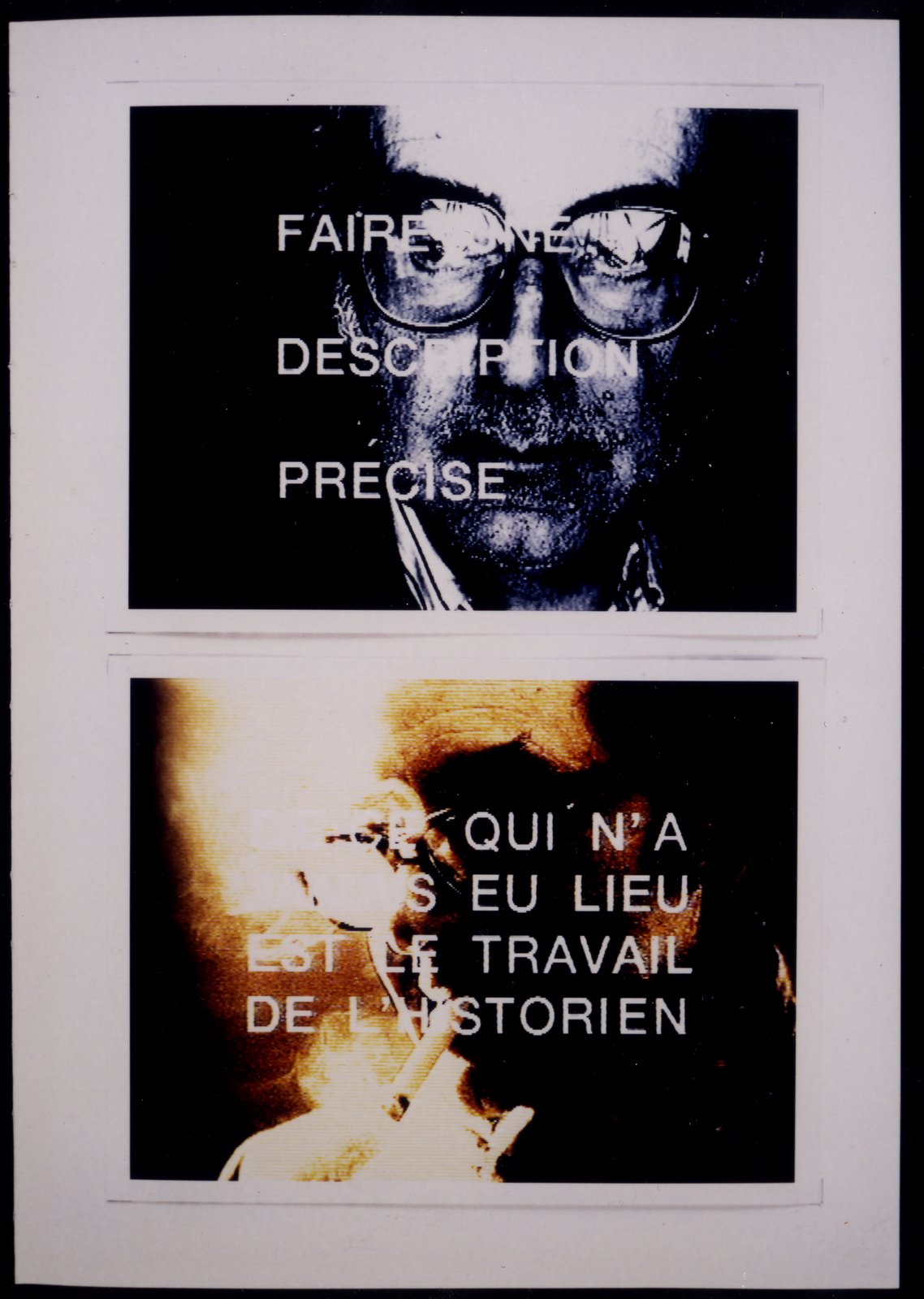

Directed and written by Jean-Luc Godard

Ironically, the two greatest works by the two most innovative filmmakers of the French New Wave, Jean-Luc Godard and Jacques Rivette, were originally designed as TV series. Rivette’s 760-minute, 16-millimeter serial Out 1 (1971) was rejected by French state TV, and he spent most of a year editing it down to a 255-minute version to show in theaters, Out 1: Spectre (1972). Less a digest than a perverse variant — some shots were rearranged so that they had radically different meanings and contexts, and much of the comedy was turned into psychodrama — it’s the only version that’s ever shown in the U.S., though it hasn’t been screened for years. The original — almost certainly the best film ever made by anyone about the 60s counterculture and its demise — still shows periodically in Europe.

Godard’s eight-part, 264-minute video Histoire(s) du Cinéma (1998), conceived and made over 20 years, has fared better, but it’s still pretty hard to come by. The only version ever sold in France is a lousy mono video transfer; a package of CDs and books in several languages transcribing major portions of the stereo sound track came out here years ago. The only decent copy of the entire work that’s available is a set of subtitled Japanese DVDs. The distributor, Gaumont, has periodically announced the upcoming release of DVDs subtitled in English, but they’ve yet to materialize.

So Godard has edited an 84-minute feature out of his magnum opus and transferred it to 35-millimeter. He calls it “Selected Moments,” but like Rivette’s Spectre, it’s more a new work than an abridgment or anthology. For starters, it lacks the emotional and expressive range of its source, which is more celebratory. But it’s a beautifully composed work — a friend compared its construction to that of a cathedral — and its views of cinema and the 20th century remain powerful. The subtitles on the lovely print the Gene Siskel Film Center is screening are sparse and incomplete, though given how many elements Godard combines, anything more would surely have been overload.

The original TV series is hard to get, supposedly because of copyright issues. In 1998 Gaumont cleared the rights to the many dozens of clips, photographs, and paintings it includes, but only for use in France. So technically the Japanese edition is illegal. Godard had contracted to draw his music, most of it classical, from the German-based ECM label, which didn’t acquire permission to use other sound elements even though chunks of them were drawn from movie sound tracks; that’s why the CDs and books have been sold here but not the videos.

Sometimes issues such as copyrights are excuses rather than reasons, and rumor has it that Godard was so late delivering the original series to Gaumont eight years ago that they were fed up with it even before it premiered on French TV — which probably accounts for why they didn’t bother to make a decent video transfer to sell in stores. If copyrights really were a major concern for Gaumont, why would it allow Moments Choisis to be shown outside France?

Histoire means “story” as well as “history,” suggesting an ambiguous and very Godardian overlap of fiction and nonfiction. The film’s major exhibits come from his own work as well as many film classics, newsreels, paintings, and still photographs, making the overall story autobiographical as well as historical — and above all mythical. As English critic Michael Witt notes, Godard so fully identifies his own life span with cinema’s that for him his death and the death of cinema have become almost interchangeable. It’s easy to mock this solipsism, which takes on additional pathos if seen in the context of Godard’s self-imposed isolation. But the audiovisual poetry he’s able to extract from this premise — and others — is much more important than whether it happens to be true.

Two myths — that cinema was an invention of the 19th century and that it wound up conveying the history of the 20th — seem to provide the basis for most of Godard’s arguments. He also gets actor Alain Cuny to recite a long passage from art historian Elie Faure on Rembrandt while he substitutes cinema for each use of Rembrandt — implying that this 20th-century art form was a dream of many preceding centuries.

Diving into a meditative, melancholy funk even deeper than that of his other late features, Godard places cinema, including his own, on trial and finds it guilty of failing to bear adequate witness to the Holocaust and other mass slaughters. We “saw nothing in Hiroshima, Leningrad, Dresden, Madagascar, Hanoi, Sarajevo,” he observes, adding, “Suffering isn’t a star.” He implies that the job of entertaining and the task of recording reality are ultimately irreconcilable and that art located somewhere between the two doesn’t necessarily build a bridge: “We’ve forgotten that village . . . but we remember Picasso, that is to say, Guernica.”

Curiously, Godard accords the ultimate honor of achieving some sort of power through art to Alfred Hitchcock, “the greatest creator of forms of the 20th century,” who “became the only poète maudit to meet with success.” We may forget the plots and situations of his films, “but we remember a handbag . . . a bus in the desert . . . a glass of milk . . . the sails of a windmill . . . a hairbrush . . . a row of bottles, a pair of spectacles, a sheet of music, a bunch of keys” because “through them and with them Alfred Hitchcock succeeded where Alexander, Julius Caesar, Hitler, and Napoleon had all failed, by taking control of the universe. Perhaps there are 10,000 people who haven’t forgotten Cézanne’s apples, but there must be a billion spectators who will remember the lighter of the stranger on the train.” We can certainly dispute these figures and the hyperbolic conclusion Godard draws from them, but the sounds and images that counterpoint this monologue are exquisite and irreproachable.

Godard’s view of Western cinema is sufficiently inclusive to allow for the alternation of a cool James Dean walking near Times Square and a shouting Ukrainian peasant (in Dovzhenko’s Earth) running across a field, but the logic is more poetic than discursive. Film buffs may find more to chew over than other viewers, but they won’t necessarily come away with more. When Godard cuts from a production photo of Chaplin directing Limelight (1952) to a clip of two women wrestlers in a ring, is it important to know that the clip is from …All the Marbles (1981), the last feature of Robert Aldrich, who can be seen as Chaplin’s assistant director in the photo? I’d argue that the musical articulations of the cutting between the two subjects matter more.