From the Chicago Reader (July 2, 2004). — J.R.

Before Sunset

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Richard Linklater

Written by Linklater, Kim Krizan, Julie Delpy, and Ethan Hawke

With Delpy and Hawke.

“The years shall run like rabbits,

For in my arms I hold

The Flower of the Ages,

And the first love of the world.”

But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

“O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time….

“O plunge your hands in water,

Plunge them in up to the wrist;

Stare, stare in the basin

And wonder what you’ve missed.”

— from W.H. Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening” (1937)

Richard Linklater, like Wong Kar-wai on the opposite side of the globe, is a lyrical and elegiac filmmaker. In many of his films, as in many of Wong’s, the subject is time — the romance and poetry of moments ticking by, the wonder and anguish of living through and then remembering an hour or a day.

Future generations may look back at Linklater and Wong as poets laureate of the turn of the century who excelled at catching the tenor of their times. In Days of Being Wild and Slacker, Ashes of Time and The Newton Boys, Happy Together and Dazed and Confused, and In the Mood for Love and Before Sunrise they’re especially astute observers of where and who we are in history. And some of their ability to grasp the zeitgeist surely derives from their special feeling for love stories. Born only two years apart, Wong (1958) and Linklater (1960) are often about a decade older than their fictional couples, which suggests they’re particularly sensitive to what might be in store for these characters.

The narratives in more than half of Linklater’s ten features take place within the span of a day. I can’t remember if this is true of his unreleased first feature, the Super-8 It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books (1988), though I suspect it isn’t; I’m not sure about his animated Waking Life either. Time isn’t compressed in his two studio productions, The Newton Boys (1998) and The School of Rock (2003). But it is in Slacker (1991), Dazed and Confused (1993), Before Sunrise (1995), SubUrbia (1997), Tape (2001), and now Before Sunset, an inspired sequel to Before Sunrise.

Only Tape and Before Sunset take place in real time, and both are more ambiguous about their characters’ motivations than the other four. For this reason, I’m tempted to call them Linklater’s most existential films — the ones that delve the deepest into the characters’ moment-to-moment decisions. Both are short — Tape runs 86 minutes, Before Sunset 80 — both star Ethan Hawke, and both anxiously hash over a former romantic relationship. In other respects they’re polar opposites. Tape is confined to a dinky motel room in Lansing, Michigan; Before Sunset skips across Paris by foot, boat, and car, moving from the left bank to the right. Tape charts suppressed hatred slowly rising to the surface; Before Sunset traces something much closer to affection and guarded love.

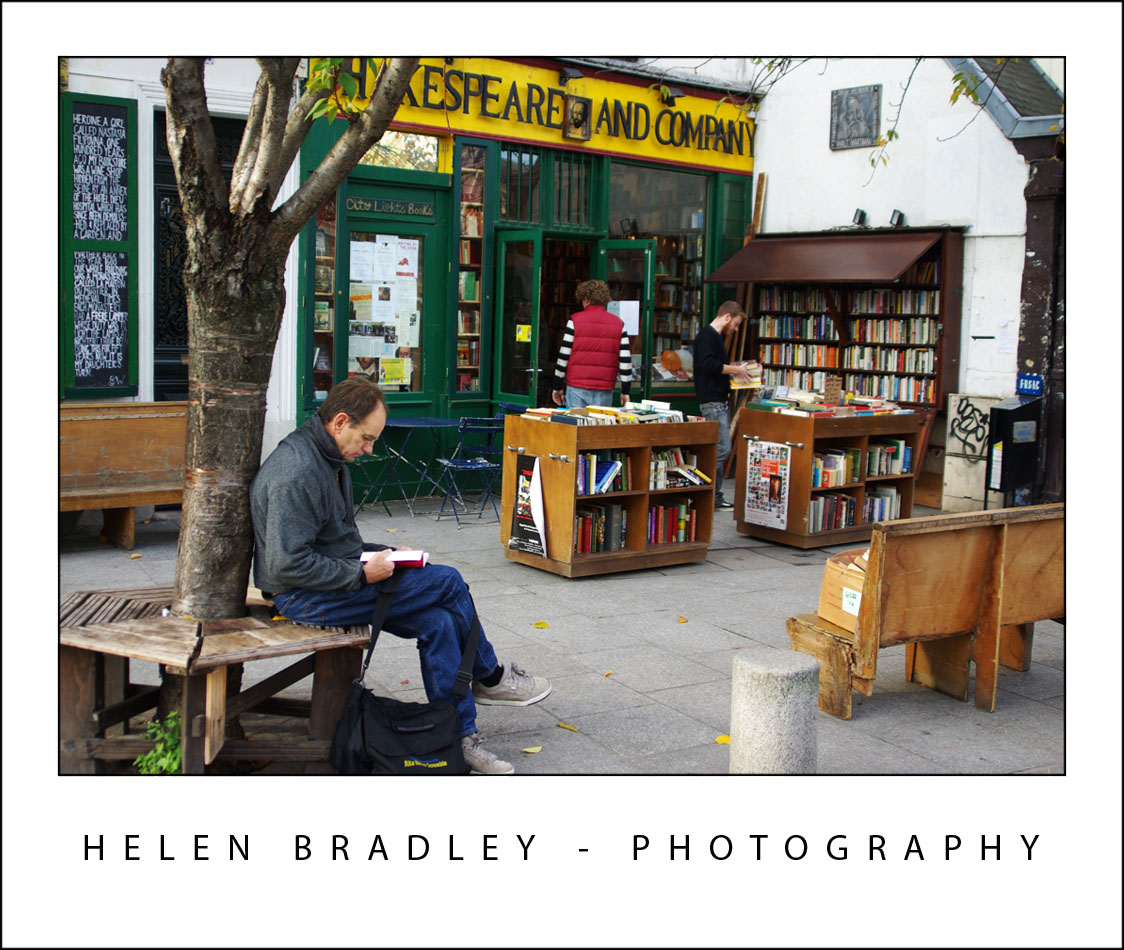

You don’t have to have seen Before Sunrise to follow the sequel, especially since Linklater gives us a few quick, silent glimpses of Jesse (Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) as they were in the first film during their day together in Vienna in 1994. In Before Sunset both characters are in Paris in 2003. He’s doing a book signing at Shakespeare & Company at the end of a 12-day, ten-city European tour promoting his novel, before returning to New York. He catches sight of Celine in the audience, and though he has only a little over an hour before a driver will take him to the airport, he suggests they have coffee. (Many reviews assume that the bookstore we see is the famous one run by Sylvia Beach, who first published James Joyce’s Ulysses; in fact, it’s a shop several blocks away that appropriated the name when it opened in the 50s in order to attract tourists — which doesn’t mean that it isn’t a respectable literary hangout in its own right, more beat than early modernist in its orientation.)

In Before Sunrise Jesse and Celine, both in their 20s, meet by chance on a train in eastern Europe. Jesse is on his way back home to Texas after breaking up with his American girlfriend in Spain; Celine is returning to Paris after visiting her grandmother in Budapest. They spontaneously decide to spend a day and then a night together in Vienna, sleeping in a park because he doesn’t have enough money for a hotel.

The day in question is June 16, sometimes known as Bloomsday, during which the entire action of Ulysses is set. Before Sunrise isn’t an especially literary movie — even though Celine is reading Georges Bataille when they meet, Jesse quotes some lines from the above Auden poem shortly before they part, and Joyce’s English translation of Gerhard Hauptmann’s first play, published posthumously in 1978, is titled Before Sunrise. I suspect that Linklater uses the Ulysses reference because, like Joyce, he’s interested in giving a lot of weight to the everyday.

When Jesse first meets Celine, he’s reading Klaus Kinski’s relatively unliterary autobiography All I Need Is Love. Nine years later he’s become a published novelist, and she’s become an activist working for an environmental group. And where Linklater’s cinematic models in Before Sunrise were Hollywood love stories such as Vincente Minnelli’s The Clock (1945), they’re now more French New Wave, Eric Rohmer in particular.

The novel that Jesse’s promoting, a minor best seller in the States, is a fictionalized version of his earlier encounter with Celine, which ended with them promising to meet again in Vienna in six months — having decided earlier that they wouldn’t exchange last names or addresses for fear of turning their relationship into something banal and routine. In the novel, as in Before Sunrise, we have no way of knowing whether the two will ever meet again. Ever since the film was released, a lot of viewers have been speculating about whether either of them would keep the date. As critic Robin Wood has pointed out, in an essay in Cineaction! (no. 41) that rapturously celebrates the film as one of the greatest ever made, such speculation is inextricably tied to the way each viewer relates to the film. Wood came very close to guessing correctly what the characters would do, though it’s possible that Linklater, who’s long been aware of the essay, was influenced by those guesses.

Having seen Before Sunset twice, and Before Sunrise again in between, I can’t say which film is better. Both seem to fulfill an ambition Jean-Luc Godard expressed in the 60s — to achieve “the definitive by chance.” That is, each in its own way attains a kind of perfection while coming across as impromptu and offhand. This is surely a sign of the greatest mastery, an accomplishment that’s plainly to the credit of Hawke and Delpy as much as Linklater and Kim Krizan, Linklater’s script collaborator on both films.

But it would be wrong to view the second film’s style as simply a continuation of that of the first. Before Sunset, shot in only 15 days, deliberately sets out to complement its predecessor right from the opening credits. During the final stretches of Before Sunrise we see a succession of places in Vienna where Celine and Jesse have spent time together in the order in which we first saw them, though neither character is present; it’s a kind of melancholy scrapbook. Reversing this process, Before Sunset begins with some of the Paris locations where Celine and Jesse will spend time together, in this case tracing their steps backward.

The switch seems appropriate, because the emphasis now is much more on anticipation — theirs and ours — and on everything the passing of time does to intensify it. Significantly, when he’s asked at Shakespeare & Company what his next novel might be about, Jesse says he wants to write a story that takes place in the time a pop song could be played. As with the watch and clock that figure in the early meetings between Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung in Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild, time itself becomes a tool of mutual seduction, the minute hand of a timepiece serving as a kind of Cupid’s arrow. So it’s hardly coincidental that Jesse’s novel is titled This Time — or that the cut on a CD he chooses to play in Celine’s apartment, which she does an elaborate actorly riff on, is a Nina Simone performance of “Just in Time.”

Perhaps because Hawke and Delpy have had nine years to think about these people, their performances have an assurance and an excitement I’ve never seen either actor display before. Before Sunset is talkier and offers us fewer distractions from the two leads than Before Sunrise.

Both characters, now in their 30s, have many more protective layers to peel away before they can gauge their feelings for each other, and the nature of those feelings is harder for them (and us) to recognize and define. Nine years ago they played a couple of impromptu games that allowed them to reveal their emotions — asking each other blunt questions on a streetcar and carrying on imaginary phone conversations with separate friends in a restaurant. Now they dissimulate more, and the ambiguities in their shifting positions suggest even they can’t always be sure whether those positions are entirely honest.

Celine, sitting in the backseat of a car with Jesse, starts to caress his head while he isn’t looking, then suddenly pulls back, and that simple curtailed gesture carries in it a sense of tragedy, the consequence of the weight of time. Yet competing with that weight is the volatile lightness of the dangerous present — the rush of passing minutes that keeps the characters and us suspended in hope. Linklater’s refusal to let go of this scary promise, even when the movie comes to an end, is a true masterstroke — and one of the most perfect endings of any film that comes to mind.