This appeared in the May 5, 1995 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

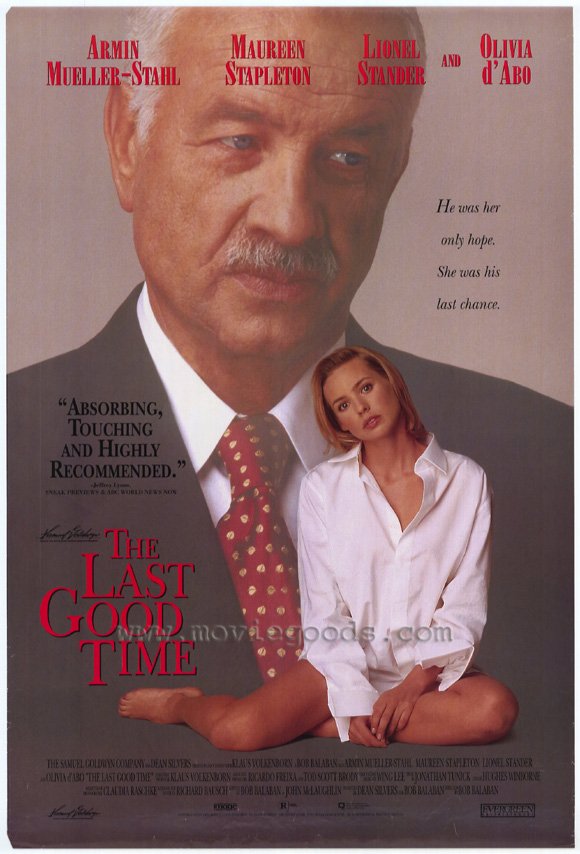

The Last Good Time

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Bob Balaban

Written by Balaban and John McLaughlin

With Armin Mueller-Stahl,Olivia d’Abo, Lionel Stander,Maureen Stapleton, Kevin Corrigan, Adrian Pasdar, and Zohra Lampert.

Bob Balaban, a native Chicagoan who’s best known as a prolific movie and stage actor, has directed only three features to date. I haven’t seen his second feature, My Boyfriend’s Back (1993), which some people tell me I’m better off having missed, but Parents, his first, was one of the most auspicious debuts of 1989.

Despite the radical differences between Parents and The Last Good Time in terms of genre, subject, style, and tone, they’re clearly the work of the same filmmaker. Part of this has to do with a precise feeling for place and a profound grasp of what sitting alone in a room feels like, even when other people are present. The solitary character in Parents is a ten-year-old boy who’s living with his parents in tacky 50s American suburbia. The monstrous (if typical) ranch-style house where they live is seen basically just as the boy experiences it — an expressionist, wide-angle nightmare etched in “cherry pink and apple blossom white” (to quote the song heard over the opening credits) that matches his parents’ taste and hypocrisy.

In The Last Good Time the solitary character is a retired immigrant violinist and childless widower named Joseph Kopple (Armin Mueller-Stahl), who’s living in a decrepit and anonymous (if typical) one-room apartment in Brooklyn. This space isn’t expressionistic or stylized in any obvious way, yet it’s amazing how expressive Balaban and his production designer, Wing Lee, make it; indeed, it’s made to say quite different things about Kopple at various times over the course of the film. Suggesting an expressionism that’s internalized and minimalist, this simply and starkly appointed space is something we experience as the inside of Kopple’s head, and the complex camera maneuvers performed within this apparently constricted arena manage to keep it both fresh and familiar, like thoughts that are both recurring and evolving. Thanks to Balaban’s compositions, which had a comparable pristine power in Parents, these thoughts are arranged before us like items in a Joseph Cornell box.

Based on a novel by Richard Bausch, The Last Good Time is as much about what it means to grow old in the 90s as Parents was about what it meant to grow up in the 50s, only this time the story is much more shaped and controlled. The plot centers on the changes in Kopple’s life when he takes in Charlotte (Olivia d’Abo), a 22-year-old neighbor from upstairs who’s physically abused by her shady boyfriend and then accidentally locked out of their apartment. Kopple allows her to sleep on his floor, and their physical proximity as well as their radical differences create an evolving dance of interactions. The film is preternaturally attuned to this dance, and Balaban’s charting of the erotics of this developing relationship couldn’t be more alert and judicious. This is a very sexy movie and a very funny one, but its definitions of what’s sexy and what’s funny aren’t standard. Furthermore it’s a movie that knows exactly where it’s going every step of the way, and every scene and shot has a specific point to make — a kind of precision filmmaking we rarely encounter these days.

An approach that is this acutely aware of itself is clearly limited when it comes to spontaneity. But it’s part of Balaban’s achievement that he never overshoots his mark by trying to go beyond what his material has to offer. Emotionally and thematically, this is a perfectly measured movie; it always knows when to cut and when to keep the camera running, it never allows a scene to become unduly rhetorical or sentimental, and it always remains entirely believable. In many respects these qualities perfectly match the control-freak personality of Kopple himself, who makes out a list not only of what to do every day but of what to wear. They also reflect the parsimonious lifestyle assumed by — and often forced on — the elderly: having to estimate how much energy one needs to get up or down a flight of stairs, for instance, is a problem that rules much of the life of Ida (Maureen Stapleton), another upstairs neighbor of Kopple’s whose solitary life contrasts with and parallels his own. (It’s a poignant moment when Ida angrily denounces Kopple in his flat for his mean-spiritedness, then has to knock at his door again to solicit his help in climbing back up the stairs.)

Economies of diverse kinds rule Kopple’s life, including economies of money, energy, memory, emotion, and philosophy (which is mainly what he reads). He tends to save what Charlotte and her obnoxious boyfriend squander, but this doesn’t necessarily mean he’s any more realistic or flexible than they are. Near the beginning of the film he’s told by a woman working for the IRS that his pension is taxable and he therefore owes the government $6,000, his entire savings; for the remainder of the movie he tries to cope with this dilemma, and part of his response is simply denial. His memory of the past is concentrated on an image of his late wife (whose picture is the only thing hanging on his wall) dancing naked before a fireplace, and his life in the present seems comparably organized around a few reliable staples. A pro like Mueller-Stahl knows this character like the back of his hand, but, like Kopple himself, he isn’t in any hurry to tell you everything he knows right away.

There are very few Hollywood movies that deal in any depth with the everyday life of old people, because, needless to say, it isn’t a subject that attracts audiences. Leo McCarey’s sublime Make Way for Tomorrow (1937) may be his greatest picture, but it was his screwball comedy of the same year, The Awful Truth, that drew the crowds and won him his first Oscar. Part of the beauty of The Last Good Time in approaching this subject is that it doesn’t try to say too much about it; it merely asks us to sit with it for a while, look at it this way and that, and arrive at a few modest conclusions. Some of these conclusions have to do with the way old people are treated in this country, but the film never mounts a soapbox; it merely allows us to see this with more clarity than usual.

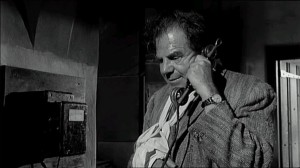

The movie features the last screen performance of the late Lionel Stander, one of the greatest of all character actors — a gravel-voiced wonder with gnomelike features, sensitive eyes, and a simian brow. He flourished in 30s and 40s movies by Ben Hecht, Frank Capra, Howard Hawks, Fritz Lang, Leo McCarey, and Preston Sturges, among others, but the Hollywood blacklist drove him overseas for most of the 50s and 60s, when he wasn’t working as a Wall Street broker. (Some of his most notable later performances were in The Loved One, Cul-de-sac, Once Upon a Time in the West, and New York, New York.) Balaban’s creating the opportunity for Stander to deliver such a perfect swan song is justification enough for this movie, but it’s a blessing that’s interconnected with the film’s other virtues; it’s another factor in the overall economy.

The character Stander plays here, Howard Singer, is Kopple’s former upstairs neighbor and only friend. He’s dying in a rest home, and the fact that Stander, born in 1908, was close to death himself clearly adds something to the size of his performance — not a trace of morbidity, which one might assume, but rather wisdom, humor, honesty, and eloquence as both the character and the actor stare death in the eye. (Something comparable comes across in Richard Bennett’s performance in The Magnificent Ambersons, though on a smaller scale; Stander takes over the film every time he appears, and he never squanders the opportunity.) Howard Singer’s memory is constantly slipping away, and he’s usually aware of this. He’s largely preoccupied with sex, which probably isn’t uncommon for someone his age, though it flies in the face of what most people expect from him. There’s a matter-of-factness about this character and this performance that’s as beautiful and as functional in the film as the simplicity and perfection of Kopple’s apartment.

In his own life Stander was something of a good-time Charlie, and Howard Singer shares this capacity. (In a 1971 interview Stander said, “There were blacklisted actors who committed suicide….But me, I have always lived on the champagne level. I figured that I needed $1,250 a week to break even, so I went to work on Wall Street, where there is no blacklist. I became a customer’s man, and I managed to live in the style to which Hollywood had accustomed me.”) When Kopple gets laid he brings a bottle of booze and cigars to the rest home to celebrate his triumph with Singer. His friend offers a toast: “Here’s to your liver and your dick.” It’s one of the nicest aspects of The Last Good Time that the precise meaning of the title remains pointedly ambiguous, though there’s clearly a suggestion that good times occasionally last longer — and come later — than they’re supposed to.