From Written By: The Journal of the Writers Guild of America, West (March 1998, Vol. 2, issue 3).

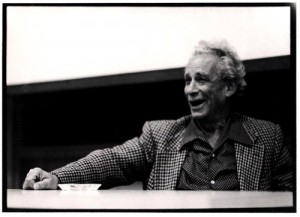

The first photograph here was taken during the summer of 1987, when I was the director of the Film Studies summer school program at the University of California, Santa Barbara and invited Sam Fuller to serve as our Artist in Residence. –- J.R.

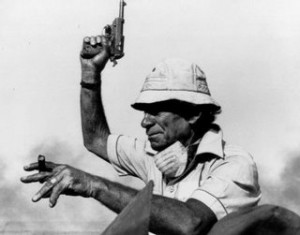

Many film lovers of my generation were introduced to him in an early party sequence in Jean-Luc Godard’s already unruly Pierrot le Fou (1965), playing himself and smoking his signature cigar-a short, wiry firecracker ready to hold forth. Asked by Jean-Paul Belmondo what cinema was, he said it was like a battleground: “Love. . .hate. . . action. . .violence. . .death. In a word, emotion.”

By the time the writer-director-legend Samuel Fuller died in Hollywood last October at age 86, his reputation as the last two of these hyphenates was fully in place. Celebrated for his gritty noirs, unglamorous war films, and eccentric westerns, he also turned up in bit parts in everything from The American Friend to 1941. Yet the fact that he’s still better known as a director and as a juicy screen presence than as a writer seriously distorts the meaning of his life and career.

Having had the privilege of knowing him as a dear friend over the last decade of his life, I heard a lot about what he called his “copy” — his prolific output as a journalist, novelist and screenwriter — and relatively little about his directing and acting. In fact, as far as he was concerned, his acting in the films of others — always somewhat extemporaneous, for he hated to memorize lines — was essentially a form of script doctoring. As he once explained the process to me, “I ask the filmmaker what the holes in his script are, then I play a character who’s designed to plug them up” — thus yielding the cinematographer in The State of Things and the compulsive Nazi hunter in A Return to Salem’s Lot, two of his more substantial roles. Similarly, I always suspected that he became a director for the same reason that Billy Wilder and Joseph L. Mankiewicz did: to preserve and protect the integrity of his scripts. Ever since he started out as Arthur Brisbane’s copy boy at the New York Standard at the age of 12 — turning over most of his earnings to his widowed mother — the word remained his bread and butter as well as his life; everything else was simply punchy presentation.

Beginning with his first feature (I Shot Jesse James, made when he was 38), he liked to start things off with a bang, and in keeping with his newspaper background, he regarded these openings as headlines. Here are the beginnings of two of his later projects, written sixteen years apart:

PROLOGUE

SMALL SCREEN BLACK AND WHITE

FADE IN

EXT. NO MAN’S LAND –- DAY (BESCARA, YUGOSLAVIA)

1 SHELLSHOCKED HORSE

runs amok…toward Christ on the Cross

2 THE EYES OF CHRIST

fill screen. Two gaping holes. Worm-filled eyes.

Broken strands of Yank, Hun and French tele-

phone lines form the Crown of Thorns. The

wooden face is bullet-chipped, cheek splintered,

nose a highway of wood lice, algae in nostrils,

fungi filling half-opened mouth, ants assaulting

beard, nails rusting in palms and feet. The

Cross supporting the towering figure looms

high on a mound that ruses twenty feet. Christ

is watching a young DOUGHBOY looking among

dead for one man. The Doughboy carries his

rifle as part of his anatomy, checking dogtags,

finds the one he’s looking for, removes it, pock-

ets it, HEARS pounding of hoofs, turns, looks

up at

3 WILD-EYED HORSE

rearing

4 DOUGHBOY

dives

5 HOOFS

stomp the rifle, splintering the stock.

6 DOUGHBOY

claws up mound to base of cross. SUPERIMPOSE

“WORLD WAR ONE”

In this film you are Ruth Snyder for 14 years.

You will share her visual and mental complexities as

you live her from 1914 to sit with her on the Chair

on January l2, 1928 and you will burn with her as

thousands of volts surge through your body –-

And then you be the judge whether Ruth Snyder

should have been electrocuted for her reason of mur-

dering her husband.

You judge whether or not she was insane for thunder-

ing her battle cry for all women in the world:

“EVERY MAN FOR HERSELF!”

The first of these hyperbolic extracts opens the “final shooting script” of Fuller’s The Big Red One (though it’s hard to imagine actual shots approximating the force of those words, dated 1977; the second comes from the second page of an unrealized treatment, The Chair Vs. Ruth Snyder, dated 1993. Apart from representing the two portions of his early life that most marked his subsequent work — his career as a crime reporter in the 1920s and his stint in the 16th Division in the 1st Infantry in the 1940s — both are characteristic Fuller openings, revealing what critic Manny Farber once described as his “comic lack of self-consciousness.” (A tireless worker, Fuller seemed to average at least two scripts and one novel a year even in his seventies.)

The same flamboyance appears in the first sequence of Girls in Prison — co-scripted by Fuller for Showtime’s Rebel Highway series in 1994, and directed by John McNaughton: A black teenager sees the corpse of her enlisted brother in Korea on TV (the year is 1953), then discovers her mother has died of a heart attack after watching the same live news broadcast; she proceeds to the studio where the xenophobic, red-baiting newscaster is still ranting, and bashes his brains out with a hammer. But this kind of loopiness is equally apparent when Fuller was simply following Hollywood conventions in his own fashion. One of the cut lines from a rugged love scene in Pickup on South Street: “I kissed a lot of guys. Sometimes it’s like kissing an orange…sometimes it’s like a grapefruit…sometimes it’s like getting your mouth caught in a laundry machine…but honest, Skip, I never felt like this…”

Ironically, for someone who lived so viscerally by words, Fuller was handicapped by several that became attached to his name in the 1960s and have clung to him like barnacles ever since: words like “primitive,” “macho,” “anti-communist,” and “right-wing.” These were words that tried to simplify some of the anomalies in his style and his politics, but they wound up confusing a lot more than they clarified.

“Primitive” was meant to account for the stark oppositions in his plots, the pulp and tabloid rhetoric that came from a reporter who thrived on sensation, and the street smarts of a city-based prole who tended to write in two-fisted slabs of socko headline type. But even though he wasn’t an intellectual — unlike his second wife Christa Lang, a German actress who collaborated on many of his late scripts (including Girls in Prison) — his favorite artists included Beethoven, Balzac, Baudelaire and Rimbaud.

“Macho” may accurately peg his gruff personal manner, but it doesn’t begin to describe the pivotal role played by strong women in many of his films — Charity Hackett (Mary Welch) in Park Row, Moe (Thelma Ritter) in Pickup on South Street, Jessica (Barbara Stanwyck) in Forty Guns, Sandra (Beatrice Kay), in Underworld, U.S.A., Kelly (Constance Towers) in The Naked Kiss — all of whom, one suspects, bore some relationship to his feisty mother, who played a major role in shaping his personality.

“Anti-communist” came from the plots of four of his 1950s features — The Steel Helmet, Pickup on South Street, Hell and High Water and China Gate — but how much these plots reflected their period and how much they reflected Fuller remains to be properly sorted out. (It’s worth noting that the North Korean Communist prisoner in The Steel Helmet scores plenty of anti-racist points about the incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps and the segregated seating of blacks on American buses — two subjects that no other Hollywood movie of 1950 was broaching. Fuller himself liked to recall that when Pickup received the Venice Film Festival’s Bronze Lion three years later, the president of the jury Luchino Visconti, was himself a party member. And in 1987, when Fuller was artist in residence at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he hit it off famously with Communist screenwriter Paul Jarrico, who was on the same faculty. (Ten years later Jarrico died tragically in a car accident within a few days of Fuller.) As for “right-wing,” this doesn’t quite square with a Democrat who threw a fundraising party for Adlai Stevenson in the 1950s, and a social crusader whose passionate stands against racism were consistent throughout his career.

But old labels die hard, and the task of summing up a contradictory unstereotypical liberal like Fuller was never easy to begin with. For all his concentration on news and real-life issues, he sometimes had a taste for allegory and parables that complicated his scenarios. (Shock Corridor has a lot to say about what’s wrong with America in 1963, but virtually nothing about the mentally ill, his ostensible subject.) A warm and life-enhancing individual bursting with youthful energy, he specialized as a writer in charting hatred, corruption, intolerance, and violence, and judging by the outcomes of his plots, his view of the chances of these problems ever being overcome was profoundly pessimistic. Yet fashionable ’90s cynicism was foreign to his temperament, and a touch of innocence was present in everything he wrote.

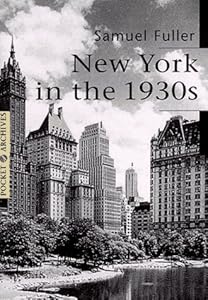

Consider his 1993 treatment for The Chair Vs. Ruth Snyder, an account of the last fourteen years in the life of the first American woman who died in the electric chair. As Fuller wrote in New York in the 1930s (Hazan: Pocket Archives, 1997), “Ruth was 33 when she was strapped into the chair for the murder of her 45-year-old husband. During the interval between her trial and execution, she attained celebrity status as a martyr to the cause of women’s rights with the feminists of the late ’20s and early ’30s.” Significantly, her lover and co-conspirator, Judd Gray, electrocuted the same day, figures in the plot only as an addendum to Snyder’s story. Fuller is much more interested in Snyder’s defense at her trial, which covers four pages and ends as follows:

Inalienable…that means rights that cannot be taken

away from a human being…and a woman is a human

being…

She’ll learn that Man was not made in God’s image.

Man was made in man’s image to be the Boss, the bet-

ter half, the ruler of the weaker sex, the despoiler of

the female that he made inferior, that he made depen-

dent…bludgeoned her with his ego and superior phys-

ical strength, stripped her of all human dignity and

feelings and emotions and ambitions, treated her like

a piece of furniture even on her back or on her

knees. . .l learned it had to be every man for herself.

My late husband Albert, in his typical superior and

masculine way, once told me that those words all men

are created equal in the Declaration of Independence

also meant all women…but I could not find even the

thought of including all women anywhere in that doc-

ument of equality written by men who declared their

fight for freedom of human beings from tyranny….

All men are created equal is man’s big lie and I could

not stand the stench of that lie so I had to get rid of

that stench permanently with the sash weight and

chloroform and picture wire. I revolted and killed my

husband for my inalienable Rights of Life, Liberty, and

the Pursuit of Happiness.

“With Fuller, one always finds both a war correspondent and a mad educator,” wrote the late French film critic Serge Daney. “He takes off from an implicit idea: The spectator knows nothing — or next to nothing.” This didactic/soapbox impulse runs through all his work, though it seldom takes the form of an unproblematical hero or heroine whose correct view of things ultimately triumphs. A sense of perpetual warfare pervades his plots, and madness is as likely to prevail as any vestige of common sense. The brutish heroes of The Steel Helmet and Shock Corridor –- an unabashedly racist sergeant (Gene Evans) fighting in Korea and a ruthless reporter (Peter Breck) who gets himself admitted to a mental ward with the scheme of solving a crime and winning a Pulitzer — wind up going insane at the end of each picture, and there is nothing resembling a replacement hero in either case to carry the viewer’s sympathies.

A typical sore-loser Fuller hero is O’Meara (Rod Steiger) in Run of the Arrow, a Confederate soldier who fires the last bullet in the Civil War and is so disgruntled by the South’s defeat that he winds up joining a Sioux Indian tribe out of spite. Skip (Richard Widmark), the pickpocket hero of Pickup on South Street, is as contemptuous of the cops as he is of the Communist agents whose microfilm he inadvertently intercepts, yet he feels some personal loyalty towards Moe, a police informer — even when she rats on him — because he figures she needs the money. Thelma Ritter was nominated for an Oscar for this part, which climaxes in a deathbed soliloquy that expresses Fuller’s grasp of Moe’s life and milieu in all its poignant ambiguity. Delivered to a Communist agent, Joey — who’s about to kill her for what she knows — this speech from the script differs only slightly from the filmed version:

Look mister, when I came in you saw an old clock

running down. You watched me flop on the bed…Know

what a change of pace is? That’s what I’m going

through. It’ll happen to you. It happens to everybody.

Corns. Bunions. Arthritis. Backache. Headache. I’m

old…and tired…and it’s so hard for me to get up in the

morning — get dressed — walk the streets — climb

stairs…and yet I keep doing it. What am I going to

do — knock it? I have to keep working to make a living

so I can die…but even a fancy funeral ain’t worth wait-

ing for if I have to do business with crumbs like you.

CLOSEUP — JOEY

MOE’S VOICE

What do I know about Commies? Nothing. But I know

one thing — I know I don’t like them!

War, newspapers and crime tend to interface and overlap in a good many Fuller scripts. In the high-energy Park Row, an 1880s newspaper staff functions like a squad in warlike skirmishes against a rival paper. Part of the importance of firing the last bullet in a war in both Run of the Arrow and The Big Red One is defining the moment when an “act of war” becomes a civilian crime and sanctified killing becomes murder. And one of the many striking differences between Fuller’s original screenplay for The Klansman and the one finally used – an adaptation of William Bradford Huie’s novel, directed by Terence Young (1974), with a script credited to Millard Kaufman and Fuller — is that the former literally concludes like a war film.

Charting racial conflict in rural Alabama during the latter stages of the civil rights movement, Fuller’s despairing script ends with the sheriff-Klansman of the title killing his best friend and his only son — both of whom fight on the side of the local blacks — in the midst of a full-scale armed combat, then declaring, “You’re better off dead…both of you.”

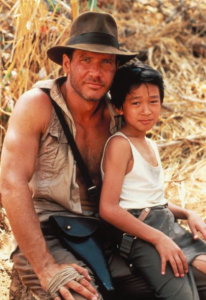

Typically, the only untarnished characters in a Fuller film are preadolescent children, like Short Round in The Steel Helmut, a South Korean war orphan who uncritically adopts the racist sergeant. (As a tribute to this trusting individual, a similar boy with the same name turns up in Indiana Jones and. the Temple of Doom.) A comparable kind of innocence informs the nameless title canine in White Dog (1981), Fuller’s most misunderstood and neglected major film — an animal trained from birth to attack blacks whose “racism” is perceived as wholly man-made.

In some respects Fuller’s most powerful antiracist statement, loosely adapted from an autobiographical book by Romain Gary, White Dog was widely misconstrued as racist by people who never saw it, chiefly as a result of earlier treatments written long before Fuller and co-writer Curtis Hanson inherited the project — with the result that Paramount ultimately shelved the feature. (To this day [in 1998] it remains unavailable on video, though it turns up periodically on cable.)

Along with the devastating experience of seeing his most ambitious film, The Big Red One (1980), cut to half its original length and drastically re-edited, it was largely this disappointment that drove Fuller into European exile in the early 1980s, where he remained until a year or so before his death. Based in Paris, where he was still a celebrity, he found it easier to land jobs and make a few pictures — Thieves After Dark, Street of No Return, The Madonna and the Dragon, Day of Reckoning — though the fact that America remained his central subject and context sometimes limited him when he had to settle for overseas locations. (In Street of No Return, based on a David Goodis novel, Lisbon has to stand in for an American city like Philadelphia.)

Yet for anyone lucky enough to be in Fuller’s company when he acted out his unmade scripts — I especially recall the action-packed openings of his Cain, his Flowers of Evil, and his Balzac — the writing and filmmaking never stopped.