From the March 1, 2002 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

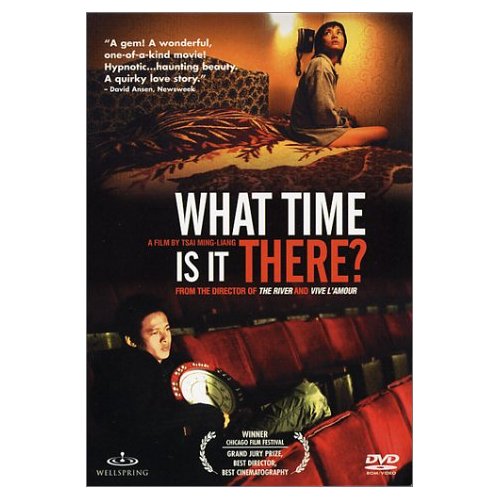

What Time Is It There?

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tsai Ming-liang

Written by Tsai and Yang Pi-ying

With Lee Kang-sheng, Chen Shiang-chyi, Lu Yi-ching, Miao Tien, Cecilia Yip, and Jean-Pierre Léaud.

After hearing the adagio of a Schubert chamber work: there is nothing more beautiful than the happy moments of unhappy men. This might serve as a definition of art. — The Diaries of Kenneth Tynan

Toward the beginning of his essay “The Crack-Up,” F. Scott Fitzgerald notes that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” That might well describe the agenda of a poetic and philosophical Taiwanese-French feature, Tsai Ming-liang’s glorious two-part invention What Time Is It There?, which premiered at Cannes last year and is opening at the Music Box this week (assuming the theater reopens after some trouble with health inspectors). It feels more contemporary, at least from a global perspective, than any other new movie in town, and central to it is an examination of separateness and togetherness, unity and disparity in two separate countries in two separate parts of the world. This is a movie deeply interested not only in what it means to be lonely, but also in what it means to perceive connection and similarity in the midst of that isolation.

It seems entirely appropriate that What Time Is It There?, Tsai’s fifth and probably best feature to date, is a Taiwanese-French production. This isn’t just because, as the title suggests, the simultaneity of action in two cities, Taipei and Paris — on opposite sides of the globe and many time zones apart — is an essential facet of the storytelling and the crosscutting that structures it. It’s also because certain qualities of thought and feeling that are found in French cinema, especially during the 60s and early 70s, are central to its aesthetic. (It also has a French cinematographer, Benoit Delhomme — a master of lighting who shot The Scent of Green Papaya and Cyclo.)

I’m thinking in particular of two French filmmakers who are quite distinct in most other respects: Jacques Rivette and Jacques Tati. Rivette is the more obvious reference point because all of his films from 1968 through 1974 (far and away his richest and most exciting period to date) — the roughly four-hour feature L’amour fou (1968), the 13-hour serial Out 1: Noli me tangere (1971), the four-hour feature Out 1: Spectre (1972), and the three-hour feature Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974) — are constructed as elaborate two-part inventions, oscillating back and forth between the members of a couple, 35- and 16-millimeter footage, theater and life, sanity and madness (L’amour fou); between various pairs of improvising actors, city and country, conspiracy and chaos (both versions of Out 1, which also move between theater and life, sanity and madness); and between two alternating stories, two heroines, and many rhyming shots and situations (Celine and Julie Go Boating).

Rivette sometimes articulates this formal pattern by planting his actors on opposite sides of the screen and waiting to see what happens — a particularly interesting experiment when their performing styles are at loggerheads (as in the movie-cartoon zaniness of Juliet Berto’s Celine versus the stagy realism of Dominique Labourier’s Julie) or when the characters are so alienated they can barely find a way to relate to each other (Jean-Pierre Léaud and Bulle Ogier in both versions of Out 1, occupying adjacent rooms in the same hippie boutique). This tragicomic mutual alienation is apparent whenever any two people are lucky or unlucky enough to occupy the same frame in one of Tsai’s pictures, and you can bet that what happens and what fails to happen between them will be equally significant — another two-part invention that can be thought of as a race between hope and futility, between narrative and nonnarrative impulses, between laughter and despair. The poet laureate of loneliness, Tsai has more ways of describing how people can feel alone when they’re together than any other filmmaker who comes to mind. That isn’t to say he doesn’t, paradoxically, have a lot of company, much of it French, when it comes to this preoccupation.

His method of subdividing the screen and splintering focal points is where Rivette comes closest to the Tati of Playtime (1967). Tati was a comic director who could place two, three, or half a dozen active or potential gags on-screen at the same time, all competing for our attention. For him, that was a lot more interesting than the one-gag-at-a-time aesthetic of Chaplin or Keaton, perhaps because his choice makes the spectator the butt of most of the comedy rather than the on-screen comic performer. Proposing a playful way of coping with sensory overload, Tati offers a new form of transaction in charting the complexity of the modern world.

Tsai never goes as far as Tati in pursuing such an aesthetic, at least within the space of a single shot, yet he’s much closer to the spirit of Tati than he is to that of Rivette, a more actor-oriented and less painterly director. When I asked Tsai at the Toronto International Film Festival last fall if he was a fan of Tati, he enthusiastically confirmed my guess. I have no idea whether he likes or even knows the films of Rivette, but he’s on record citing as his all-time favorite film the first feature by Rivette’s friend and former critical colleague François Truffaut, The 400 Blows — a film that’s quoted at length in What Time Is It There? It’s worth noting that the two-part inventions of Rivette are derived in many respects from the rhyming shots in Alfred Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (most of them rhymes between shots featuring either Teresa Wright or Joseph Cotten, who play a niece and uncle, both named Charlie), which were identified and analyzed by Truffaut in a highly influential article called “Skeleton Keys.” This analysis inspired Truffaut’s colleagues Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, and Rivette to trace similar patterns in other Hitchcock films, a process that undoubtedly inflected some of their subsequent filmmaking.

It’s also worth pointing out that Hitchcock and the Truffaut of The 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player, and The Green Room are themselves poets of loneliness — which undoubtedly has something to do with why they, Rivette, Tati, and Tsai are all in love with the formal rhymes that can be made between and around the lonely vigils of isolated individuals, a giddy kind of pattern making that each of them expresses differently.

A father dies, and in their separate ways his wife and son mourn him in a small flat in Taipei, where they’re keeping his ashes. The wife tries to summon back his spirit with Buddhist priests, chants and rituals, and bowls of food; the son mainly stays cooped up in his room, peeing into various plastic containers, though in the daytime he sells watches on the street. A young woman who’s about to fly to Paris tries to get him to sell the dual-time watch he’s wearing, and after some hesitation — he considers it bad luck to sell something personal after a death in the family — he agrees. But he winds up obsessing about Paris and the time difference between the cities, which compels him to reset as many local watches and clocks as possible to Parisian time.

Meanwhile, Tsai crosscuts between the loneliness of the wife and son and the loneliness of the young woman in Paris, about whom we know relatively little. We can’t even be sure whether she’s simply on vacation or has a particular mission in mind. The latter is suggested but not confirmed by a phone call she almost makes and by a phone number she’s looking for while seated on a bench in a cemetery. Seated next to her on the bench is Jean-Pierre Léaud, the actor who played the solitary boy hero of The 400 Blows 40-odd years ago. Back in Taipei — to cite only one of many visual rhymes contained in a single shot — the son sits alone in his room watching a bootlegged video of the film.

In this typical Tsai composition the son and the TV screen, situated at the left and right edges of the frame, are both slightly slanted diagonally toward the camera, so that there’s no head-on confrontation between the character and the TV or the viewer and the camera subjects. There’s a subtle visual rhyme between the son, hunched under a quilt, and Léaud on the TV screen, hunched under a heavy checkered shirt while standing in a fairground centrifuge ride; that the camera is placed in roughly the same relation to and at about the same distance from each subject makes them register like the equally weighted sides of a scale.

The video of The 400 Blows, a ‘Scope film, is scanned, so about a third of the original wide-screen image is missing, but because Truffaut uses center framing, the loss is less serious than a video scanning of What Time Is It There? (I recently saw one, and it bisected both the son and the TV screen, reducing the power of this shot considerably. If you decide to wait and see this film on video, you might wonder what all the fuss was about.) Much later in the film, a similarly composed shot places the father’s framed portrait on a table at frame left and the bereft widow, stretched out on her bed masturbating with the container of her husband’s ashes, at frame right. As in a scene when the young woman in Paris winds up in bed with a woman from Hong Kong (Cecilia Yip) she’s met in a cafe, avoiding eye contact seems to be the premise around which all the action is organized. Yet the sense of monumentality Tsai brings to such absences — a quality that doesn’t carry over much to the small screen — has a lot to do with what makes him a major director.

I won’t give away the film’s beautiful and mystical conclusion except to remark that what it accomplishes formally is the most unexpected yet appropriate visual rhyme of all, bringing us all the way back to the beginning of the film. It’s a rhyme, like so many others here, that we can feel emotionally before we start to process it intellectually — which helps explain why both times I’ve seen this film projected in 35-millimeter, first with a large festival audience and then at a well-attended press screening, you could have heard a pin drop. Though the film avoids a strong linear narrative in favor of an overall episodic focus on everyday activities, it has an uncanny capacity to make everything it shows seem important. And the absence of music only helps to accentuate the impact of individual sound effects, which are as pronounced as in any Tati film.

Tsai’s previous features have used the same lead actor (Lee Kang-sheng, the son here), the same actors playing the lead’s mother (Lu Yi-ching) and father (Miao Tien), the same apartment (which happens to be Lee’s), and even the same fish (“Fatty”) in a tank inside the apartment. (The young woman, Chen Shiang-chyi, is also someone Tsai has worked with before — in The River and, according to him, in “a play in Hong Kong, a TV commercial, and two performances put on by the local Buddhist temple in my hometown in Malaysia.”) All of his features also share an obsession with water as well as loneliness, and the repetition of such elements has led some critics to tag Tsai as a minimalist. What this tag ignores is that each of his features is richer and more multifaceted than the one preceding it.

There’s another major filmmaker, less known than Tati or Rivette, who excelled in Tsai’s kind of two-part invention. Paul Fejos, who was born in Hungary but is best known today for his 1928 Hollywood masterpiece Lonesome (which started as a silent film but was widely released as a talkie), created his own version of urban loneliness in that film, explicitly using a diptych form. The hero and heroine first meet halfway through the film, though their day in New York City and Coney Island is charted simultaneously in splitscreen fashion — a continuing metaphor for the discontinuity of modern life as it’s experienced in a big city. They meet, fall in love, then lose each other in a crowd. In despair, they each give up the search and return to their solitary flats — only to discover, when one of them puts on a record (the talkie version’s theme song, “Always”) the other one recognizes, that they’re next-door neighbors.

There’s no such scene of synthesis or coming together on the part of the son and young woman in What Time Is It There? — not necessarily because Tsai is less hopeful than Fejos, but because he realizes that the synthesis that matters the most is the one that Tati was aiming for: the one taking place inside each spectator, not the one that appears on-screen. It’s his own way of thinking globally, of finding hope in the midst of despair, of seeing a profound connectedness in the midst of alienation, and it carries a lift that could enlighten us all.