From the April 1, 1993 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

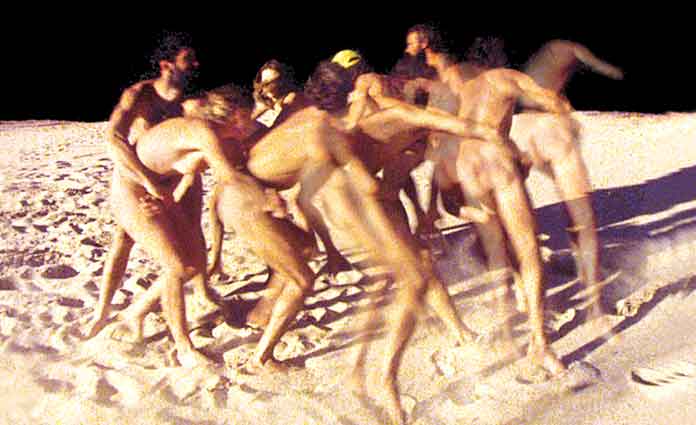

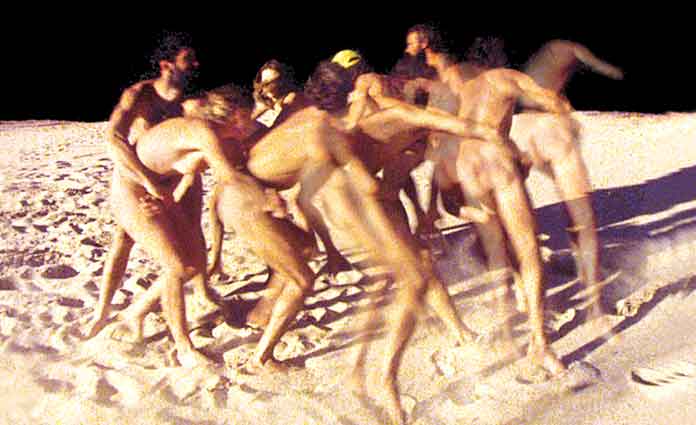

Michelangelo Antonioni’s sexy art-house hit of 1966, which played a substantial role in putting swinging London on the map, follows a day in the life of a young fashion photographer (David Hemmings) who discovers, after blowing up his photos of a couple glimpsed in a park, that he may have inadvertently uncovered a murder. Part erotic thriller (with significant glamorous roles played by Vanessa Redgrave, Sarah Miles, Verushka, and Jane Birkin), part exotic travelogue (featuring a Yardbirds concert, antiwar demonstrations, street mimes, one exuberant orgy, and a certain amount of pot), this is so ravishing to look at (the colors all seem newly minted) and pleasurable to follow (the enigmas are usually more teasing than worrying) that you’re likely to excuse the metaphysical pretensions — which become prevalent only at the very end — and go with the 60s flow, just as the original audiences did. 111 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

This book review appeared in the December 14, 1984 issue of the Los Angeles Reader. For more on Wurlitzer, readers are invited to check out my reviews of Walker and Candy Mountain in the Chicago Reader, both available on this site, as well as a more comprehensive piece about his work as a novelist and screenwriter, published in Written By. — J.R.

Slow Fade

By Rudolph Wurlitzer

Alfred A. Knopf: $13.95

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

The difference between the art novel and the Hollywood novel can be as vast as the reaches between the East coast and the West coast, and any effort to wed the two in a shotgun marriage is liable to blow up in one’s face. Slow Fade, while an exceptionally and deceptively easy read, is far from being an easy book — which is one of the best things about it. That’s probably what Michael Herr means by “dangerous” in his jacket-blurb patter: “Slow Fade comes out of the space between real life and the movies and closes it up for good. A great book: beautiful, funny, and dangerous.” Any novel that begins with one character losing an eye and ends up with another losing his index finger is bound to be fraught with scary Oedipal tensions, and Slow Fade goes out of its way to make the most out of them. Read more

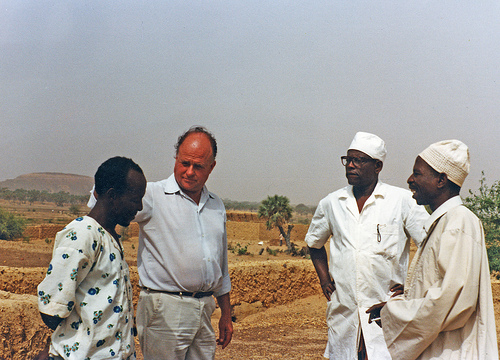

As I recall, this article, published in the November 2, 1990 issue of the Chicago Reader, had two immediate consequences for me. The first was that the late Gene Siskel, an acquaintance of mine from press screenings, refused to speak to me for several years, and I was no longer able to attend any more press screenings in Chicago held mainly for him and Roger Ebert. The second was that on November 11, when Rouch appeared at the Film Center, he publicly thanked me for my article, which I don’t believe had ever happened to me before with a filmmaker. So one might say that I lost an acquaintance (at least until Gene decided to forgive me several years later, after I attended a tribute to him and Roger at the Music Box) and gained a friend. —J.R.

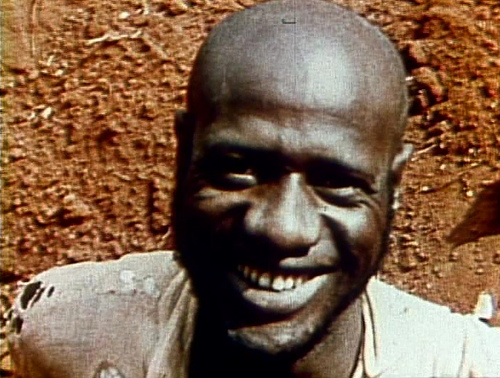

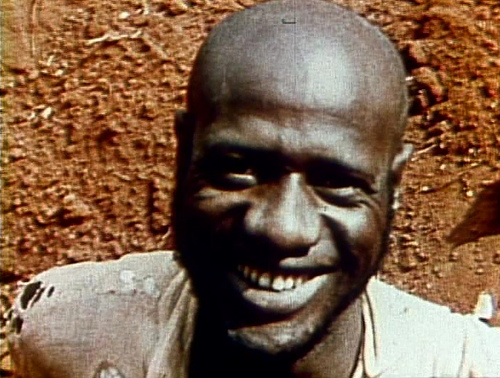

LES MAÎTRES FOUS

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Rouch.

THE LION HUNTERS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jean Rouch

With Tahirou Koro, Wangari Moussa, Belebia Hamadou, Ausseini Dembo, Sidiko Ko ro, and Ali the apprentice.

JAGUAR

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Jean Rouch

With Damoure Zika, Lam Ibrahim Dia, and Illo Gaoudel.

Anthropologists of the year 2090 — if humanity still exists and is still sufficiently divided, sufficiently colonialist and hierarchical, to need anthropologists — may look with wonder at that revealing artifact of late-20th-century multinational capitalism, the American newspaper. Read more

From the December 24, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Ten Best Movies of the 90s

(not including but with notes on Cradle Will Rock)

Does one’s integrity ever lie in what he is not able to do? I think that usually it does, for free will does not mean one will, but many wills conflicting in one man. Freedom cannot be conceived simply. It is a mystery and one which a novel, even a comic novel, can only be asked to deepen. — From the preface to Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood

A lot of havoc is wreaked by the usual annual ten-best lists. For starters, there’s the hard-sell behavior of publicists trying to get critics to see every major year-end release before December 31, even though most of these features won’t open in Chicago until at least January. This results in two time frames — one for national releases and another for local releases — which confuses everyone. If you play by the rules of the Chicago Film Critics Association (which should really be called the Chicago Film Publicists Association), you’re encouraged to act like a publicist and promote features on your ten-best list that haven’t opened in Chicago — but you’re strictly forbidden to act like a critic and review any of them. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 1993). — J.R.

DAVE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Ivan Reitman

Written by Gary Ross

With Kevin Kline, Sigourney Weaver, Frank Langella, Kevin Dunn, Ving Rhames, and Ben Kingsley

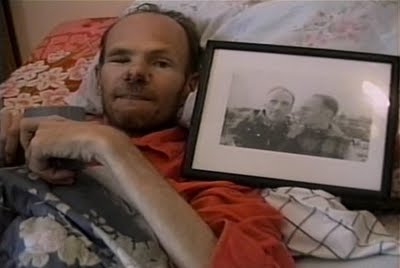

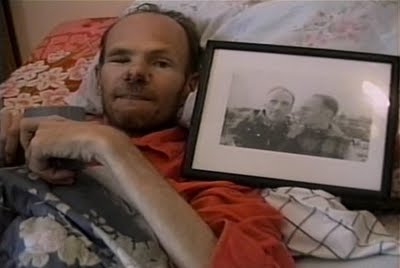

SILVERLAKE LIFE: THE VIEW FROM HERE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman

With Tom Joslin, Mark Massi, Charles and Mary Joslin, Whitey and Sue Joslin, and Lois Black Hill.

Is it the prime purpose of every movie we want to see to tell us comforting lies? On some level I suspect it is, and paradoxically this may be the case even with pictures that supposedly break through reassuring deceptions to give us the unvarnished truth. One way or another, even the best of films tend to deceive us about certain matters — and if they didn’t, we probably wouldn’t give them the time of day.

The two recent examples I have in mind are in other respects about as different as movies can be. With a skillful piece of Hollywood pastry like Dave, an Ivan Reitman comedy about a small-time businessman named Dave (Kevin Kline) impersonating the U.S. president (Kline as well), one might at first be drawn in by its refreshing candor about the ignobility of the office of president. Read more

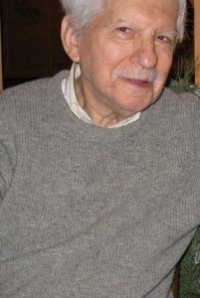

On October 14, 2012 I received the sad news from Pierre Bayle d’Autrange that his longtime partner Eduardo de Gregorio, also a longtime friend of mine (since 1973), died Saturday night at the St. Louis Hospital in Paris, not long after his 70th birthday.

I wrote the following for the festival catalogue of the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in 2004, to accompany a retrospective of Eduardo’s films — as far as I know, the only such retrospective that was ever held. It is also reprinted — along with a short essay of the same length on Sara Driver (also the subject of a BAFICI retrospective that year)– in “Two Neglected Filmmakers,” a piece included in my most recent collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia as well as here. — J.R.

Eduardo de Gregorio’s Dream Door

It must be a bummer to be an Argentinian writer and/or filmmaker and constantly get linked to Jorge Luis Borges. It must be especially hard if you’re Eduardo de Gregorio, whose first major screen credit is on an adaptation of “Theme of the Traitor and Hero” for Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1970 feature The Spider’s Strategm.

I don’t mean to question the credentials of de Gregorio as a onetime student of Borges — just the appropriateness of a too-narrow understanding to impose on a singular body of work that owes as much to cinematic references as to literary ones, and one that indeed juxtaposes the two almost as freely as it juxtaposes different languages and historical periods (while including all the cultural baggage that comes with each of them). Read more

I can’t remember precisely when it was that I first met Elliott in Paris, but I’m sure it was in the early 70s, and I suspect it was the late Carlos Clarens, another Cinematheque regular, who introduced us, most likely after some Palais de Chaillot screening. It wasn’t much later when I discovered we were neighbors living a few blocks apart — me in a small, sunless flat on Rue Mazarine, Elliott in a large room stuffed with all sorts of arcane memorabilia at the Hotel de Verneuil on Rue de Verneuil. He was already a pack-rat then, especially when it came to his collection of clippings, and he continued to live that way years later when he eventually moved back to New York — first to a hotel on lower 5th Avenue, then to a roomy loft in Soho on West Broadway. It was a tragic moment for him when he had to move out of the latter place, leaving behind or giving up many of his treasured possessions (including, as I recall, a table once owned by Robert Ryan). And only a few days ago, at the Viennale, hearing about the ravages of Sandy on New York and environs, my friends and I were concerned about whether or not Elliott was okay. Read more

From the November 11, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

*** OLEANNA

(A must-see)

Directed and written by David Mamet

With William H. Macy and Debra Eisenstadt.

David Mamet’s four features to date, none of them realistic, are all concerned to a greater or lesser extent with con games. Ultimately what one thinks of any of them has a lot to do with which side of the con one winds up on — which proves to be a matter of how one relates to the style as well as the content. Language is the major instrument of both seduction and deception in these films, and Mamet’s stylized use of it, playing on its ellipses and ambiguities as well as its more abstract and musical qualities, often deceives and seduces the audience. So how one responds to these characters has a lot to do with how one reacts to these language games.

To my mind, House of Games and the first half of Things Change are seductive (if brittle) fantasies about the allure and danger of spinning seductive fantasies; the second half of Things Change and Homicide are outsized sentimental bluffs. All three films star Joe Mantegna, are about criminals, and bear some relation to Hollywood genres; but where one places one’s trust and emotional allegiances is different in each case. Read more

This started out as an essay commissioned by Criterion for their 2011 DVD release and submitted to them in February. They weren’t happy with the result, so we agreed to disagree. — J.R.

When all the archetypes burst in shamelessly, we reach Homeric depths. Two clichés make us laugh. A hundred clichés move us. For we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, and celebrating a reunion. – Umberto Eco on Casablanca

My nightmare is the H Bomb. What’s yours? – Marilyn Monroe’s notes for her responses to a 1962 interview, first published in 2010

As I wrote in my capsule review of Insignificance for the Chicago Reader,

Nicolas Roeg’s 1985 film adaptation of Terry Johnson’s fanciful, satirical play — about Marilyn Monroe (Theresa Russell), Albert Einstein (Michael Emil), Joe DiMaggio (Gary Busey), and Senator Joseph McCarthy (Tony Curtis) converging in New York City in 1954 — has many detractors, but approached with the proper spirit, you may find it delightful and thought-provoking. The lead actors are all wonderful, but the key to the conceit involves not what the characters were actually like but their clichéd media images, which the film essentially honors and builds upon. The Monroe-Einstein connection isn’t completely contrived. Read more

This is fourth in an ongoing series of five lists of lists.(Sorry that I haven’t been able to fix the format irregularities.) –J.R.

Chicago Reader, 2000:

The Wind Will Carry Us (Abbas Kiarostami)

Rosetta (Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne)

Beau Travail (Claire Denis)

Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (Jim Jarmusch)

The River (Tsai Ming-liang)

The House of Mirth (Terence Davies)

The Smell of Camphor, the Scent of Jasmine (Bahman Farmanara) + The Child and the Soldier (Seyyed Reza Mir-Karimi)

Khroustaliov, My Car! (Alexei Guerman)

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee)

Kikujiro (Takeshi Kitano)

Chicago Reader, 2001:

A.I. Artificial Intelligence (Steven Spielberg)

Waking Life (Richard Linklater)

The Circle (Jafar Panahi)

ABC Africa (Abbas Kiarostami)

The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (John Gianvito)

Gohatto (Taboo)(Nagisa Oshima) + Chunhyang (Im Kwon-Taek)

Yi Yi (A One And A Two…)(Edward Yang) + In The Mood For Love (Wong Kar-wai)

What Time Is It There? (Tsai Ming-liang)

Mulholland Dr. (David Lynch) + Ghost World (Terry Zwigoff)

Boesman & Lena (John Berry)

Chicago Reader, 2002:

*Corpus Callosum (Michael Snow)

Platform (Jia Zhiang-ke)

Y tu mama tambien (Alfonso Cuaron)

I’m Going Home (Manoel de Oliveira)

Ellipses, Reels 1-4 (Stan Brakhage)

Russian Ark (Alexander Sokurov)

The Cat’s Meow (Peter Bogdanovich) Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (Jean-Luc Godard) Far From Heaven (Todd Haynes) 8 Mile (Curtis Hanson)

Chicago Reader, 2003:

25th Hour (Spike Lee) + Crimson Gold (Jafar Panahi) Down With Love (Peyton Reed) In the Mirror of Maya Deren (Marta Kudlacek) Pistol Opera (Seijun Suzuki) The School of Rock (Richard Linklater) The Same River Twice (Robb Moss) + My Architect: A Son’s Journey (Nathaniel Kahn) Cold Mountain (Anthony Minghella) Masked and Anonymous (Larry Charles) + The Shape of Things (Neil LaBute) Oporto of My Childhood (Manoel de Oliveira) + Joy of Madness (Hana Makhmalbaf) All the Real Girls (David Gordon Green) + Sweet Sixteen (Ken Loach)

Chicago Reader, 2004:

The Big Red One: The Reconstruction (Samuel Fuller)

Million Dollar Baby (Clint Eastwood)

Moolaadé (Ousmane Sembene)

Los Angeles Plays Itself (Thom Andersen)

The Exiles (Kent Mackenzie)

The Saddest Music in the World (Guy Maddin)

Before Sunset (Richard Linklater)

Young Adam (David Mackenzie)

Coffee and Cigarettes (Jim Jarmusch)

Springtime in a Small Town (Tian Zhuangzhuang) Read more

From the Autumn 1974 Sight and Sound.

In the spring of 1970, Jacques Rivette shot about thirty hours of improvisation with over three dozen actors. Out of this massive and extremely open-ended material have emerged two films, both of which contrive to subvert the traditional movie going experience at its roots. Out 1, lasting twelve hours and forty minutes, has been screened publicly only once (at Le Havre, 9-10 September 1971) and remains for all practical purposes an invisible, legendary work. (Its subtitle, significantly, is Noli Me Tangere.) Spectre, which Rivette spent the better part of a year editing out of the first film — running 255 minutes, or roughly a third as long — was released in Paris earlier this year. And during the interval between the editing of Spectre and its release, Rivette shot and edited a third film, Céline et Julie vont en Bateau, 195 minutes in length, which surfaced in Cannes last May. The differences between and Spectre and Céline et Julie vont en Bateau are considerable: they are respectively the director’s “heaviest” film and his “lightest,” probably the least and most accessible of his six features to date. Read more

The BBC has just asked me for this list. I took care to split this evenly between fiction and non-fiction. — J.R.

1. The House is Black (Forough Farrokhzad, 1963)

2. The Enchanted Desna (Yulia Solntseva, 1964)

3. Mix-up ou Méli-Mélo (Françoise Romand, 1986)

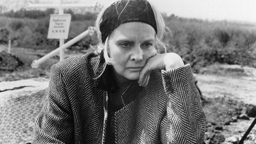

4. Vagabond (Agnès Varda, 1985)

5. The Asthenic Syndrome (Kira Muratova, 1989)

6. Passionless Moments (Jane Campion, 1983)

7. From the Other Side (Chantal Akerman, 2002)

8. You Are Not I (Sara Driver, 1981)

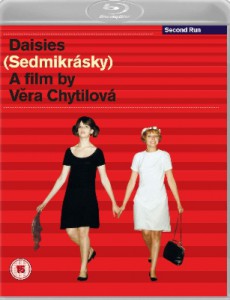

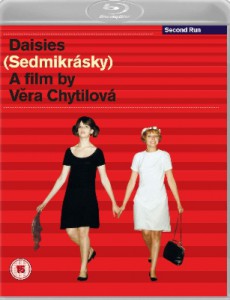

9. Daisies (Vera Chytilová, 1966)

10. Aragane (Oda Kaori, 2015) Read more

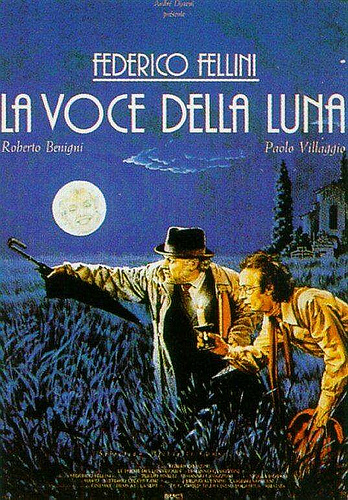

From the Chicago Reader (December 1, 1995). — J.R.

The Voice of the Moon

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Federico Fellini

Written by Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, and Ermanno Cavazzoni

With Roberto Benigni, Paolo Villaggio, Nadia Ottaviani, Marisa Tomasi, and Angelo Orlando.

Casino

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese

With Robert De Niro, Sharon Stone, Joe Pesci, James Woods, Don Rickles, Alan King, Kevin Pollak, and L.Q. Jones.

If I had the choice of seeing either Martin Scorsese’s latest (Casino) or Federico Fellini’s last (The Voice of the Moon) a second time, I’d opt for the Fellini. Both films are relatively minor works by relatively major filmmakers, though Scorsese has described The Voice of the Moon as one of Fellini’s “better pictures.” But Fellini’s swan song has a sweetness and sadness because it represents a kind of local — that is to say national — filmmaking that seems to be quickly vanishing from the mainstream. It isn’t hard to understand why no U.S. distributor has picked up this 1990 movie: it’s too Italian, and it isn’t at all easy to follow as storytelling, because it digresses all over the place. Yet these qualities, which are part of the film’s charm and poetry, might have worked in its favor outside Italy 30 years ago, when audiences tended to be more curious about other cultures and other forms of storytelling. Read more

It would obviously be hyperbolic for me to claim that the editorial evisceration originally suffered by this article was comparable to some of the curtailments experienced by Richard Pryor when he appeared on TV or in the Hollywood mainstream, but that’s more or less what it felt like to me at the time. I recently and very belatedly uncovered all but the last paragraph or so of my original version (after posting mainly the published version several months earlier), which I’ve reinstated here [on November 14, 2011]. The fact that the editor who placed this article in a lead section of Film Comment’s July-August 1982 issue entitled “The Coarsening of Movie Comedy” also changed my title to “The Man in the Great Flammable Suit” may give some notion of what his evisceration felt like at the time.

My working assumption in restoring original drafts on this site, or some approximation thereof, isn’t that my editors were always or invariably wrong, or that my editorial decisions today are necessarily superior, but, rather, an attempt to historicize and bear witness to my original intentions. It was a similar impulse that led me to undo some of the editorial changes made in the submitted manuscript of my first book, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), when I was afforded the opportunity to reconsider them for the book’s second edition 15 years later (now out of print, but available online here) — not to revise or rethink my decisions in relation to my subsequent taste but to bring the book closer to what I originally had in mind in 1980. Read more

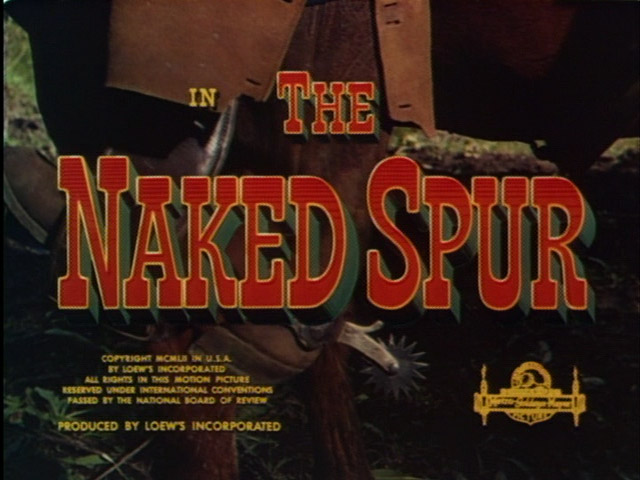

From the June 5, 2002 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Naked Spur

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Anthony Mann

Written by Sam Rolfe, Harold Jack Bloom

With James Stewart, Janet Leigh, Robert Ryan, Ralph Meeker, and Millard Mitchell.

Man of the West

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Anthony Mann

Written by Reginald Rose

With Gary Cooper, Julie London, Lee J. Cobb, Arthur O’Connell, Jack Lord, John Dehmer, Royal Dano, and Robert Wilke.

Q: What is the starting point for The Naked Spur?

A: We were in magnificent countryside — in Durango — and everything lent itself to improvisation. I never understood why almost all westerns are shot in desert landscapes! John Ford, for example, adores Monument Valley, but I know Monument Valley very well and it’s not the whole west. In fact, the desert represents only one part of the American west. I wanted to show the mountains, the waterfalls, the forested areas, the snowy summits — in short to rediscover the whole Daniel Boone atmosphere: the characters emerge more fully from such an environment. In that sense the shooting of The Naked Spur gave me some genuine satisfaction. –Anthony Mann in a 1967 interview

This seems to be landscape week at the Gene Siskel Film Center, with Abbas Kiarostami’s sublime Where Is the Friend’s House? Read more