From the Chicago Reader, January 15, 1993. — J.R.

INFLATION

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Cyril Endfield

Written by Endfield, Gene Piller, Michael Simmons, E. Maurice Adler, and Julius Harmon

With Edward Arnold, Horace McNally, Esther Williams, and Vicky Lane.

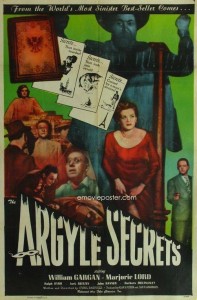

THE ARGYLE SECRETS

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Cyril Endfield

With William Gargan, Marjorie Lord, Ralph Byrd, Jack Reitzen, John Banner, Barbara Billingsley, Alex Fraser, George Anderson, Mary Tarcai, and Kenneth Greenwald.

It’s a virtual truism that rewriting history entails — and to some extent derives from — rethinking the present moment. Just as the recent change in presidents can be linked to the public’s revised reading of the last 4 (or 8 or 12) years, our highly selective sense of film history is determined not only by which films have survived but also by the present-day concerns that dictate what interests us about the past.

Illustrations of this principle can be found in three separate programs showing this week at the Film Center. The first two are part of an invaluable series, “Romanov Twilight: Early Russian Cinema,” running throughout this month. I haven’t previewed the films for these programs — Yakov Protazanov’s two-part Satan Triumphant (1917) on Saturday at 4:30 and Evgenii Bauer’s Yuri Nagorny (1916) and V. Tourhansky’s The Lord’s Ball (1918) on Tuesday at 6 — but the several others in the series I’ve seen persuade me that they’ll prove eye-openers about an era of Russian film history that’s been distorted and almost eclipsed in our minds and in film histories by the revolutionary Russian cinema that came immediately afterward.

Unlike the montage films of Dovzhenko, Eisenstein, Kuleshov, Pudovkin, and Vertov, the recently rediscovered prerevolutionary Russian cinema is a cinema of mise en scene rather than editing, and its themes and biases — which are remarkably feminist, nonmoralizing, and wedded to tragic endings — are equally distinct. It’s exciting new terrain precisely because recent historical changes have suddenly made it visible — materially visible through glasnost, ideologically visible through developments in feminist thought, and visible in other ways made possible by advances in film theory. University of Chicago film scholar Miriam Hansen, who has been studying some of these films, argues for instance that the critique of patriarchy found in many early Russian films centering on women is intimately tied to certain narrative structures — structures she sees as distinct from those in “both the emerging classical cinema in the United States and . . . the Soviet tradition.”

Another kind of reevaluation of film history this week at the Film Center is the program devoted to American writer-director Cyril Endfield, who was forced by the Hollywood blacklist to move to England in 1952, after making seven features here; he continued working for another two decades and made an additional 14 features. For a number of reasons — Endfield’s work in low-budget genre filmmaking, the way his ouevre was split between two countries, the limitations of most accounts of the blacklist, and above all the unavailability of several key works — Endfield remained critically unrecognized throughout his career and for almost two decades afterward. Lately there’s been a gratifying effort in both England and the United States to make up for this neglect — including the Film Center’s pioneering retrospective last July, a subsequent Endfield tribute at the Telluride film festival, a column by Todd McCarthy in Daily Variety, several pages in Brian Neve’s recently published English book Film and Politics in America: A Social Tradition, and programs currently being prepared for both BBC TV and National Public Radio. All the things that are so fascinating and impressive in Endfield’s work today, which we wouldn’t or couldn’t see 10, 20, 30, or 40 years ago, have to do with auteurism (his style and thematic preoccupations are both highly personal), with the visual and thematic characteristics of film noir, with our limited vision of the blacklist, with the way social criticism has evolved, and with the way film history gets written or rewritten.

As more Endfield works become available, this reevaluation and discovery will undoubtedly continue. At present, only four of Endfield’s important movies — his masterpieces Try and Get Me! (1951) and Zulu (1964) as well as The Underworld Story (1950) and Sands of the Kalahari (1965) — are available in this country on videotape or laserdisc. But two other important works, both of them scarcer than hen’s teeth and only recently located, are playing at the Film Center on Thursday, January 21. Both are genuine revelations and vital pieces of the Endfield puzzle. Indeed, based on what Endfield and his biggest early supporter, French distributor-critic-filmmaker Pierre Rissient, have told me, these should probably be considered his two most significant early works.

One is his very first film, Inflation — a 15-minute wartime propaganda short made at the request of the Office of War Information and copyrighted by MGM in 1943 but never released (thus I didn’t even know of its existence last summer when I wrote about Endfield’s career). Endfield took over the writing of the script, though official screen credit is assigned to four other people. The film received a trade showing and was “sneaked” in a few theaters; the trade press reviewed it favorably, and Endfield recalls that 700 copies — about three times the usual number — were struck for distribution. But just before the prints were ready to be shipped, Nicholas M. Schenck — the president of Loew’s, Inc., MGM’s parent company — sent a cable to producer Buddy Adler saying that the national Chamber of Commerce had requested that the short be suppressed. No reason was given, but MGM was clearly not interested in defying the Chamber of Commerce and quickly complied. Over the next half century the film was publicly screened only once, at Telluride last summer.

The other early, rare work is Endfield’s third feature, and the first he seems to recall with any affection — The Argyle Secrets (1948), a Z-budget thriller he hastily adapted from a radio script and reportedly shot in about six days. The differences between Inflation and this film and the available copies of each are dramatic — a pristine 35-millimeter print of a short with stars made at Hollywood’s most opulent studio versus a scratchy, beat-up 16-millimeter print (alas, the only one to be found) of an independent effort shot without stars and on a skid-row budget. (Intriguingly, the late film distributor Raymond Rohauer — who was associated with reissues of silent pictures by Buster Keaton and D.W. Griffith — is credited as “assistant to the producer” on The Argyle Secrets.) These two fascinating period pieces eloquently testify to Endfield’s potent pessimism about human weaknesses, specifically in relation to World War II, as well as to his outsize filmmaking talent.

Inflation offers us two patriarchs seated behind desks, each of whom intones a documentary-footage voice-over when he isn’t seen addressing the camera or talking into a telephone receiver. One of them — literally the Devil (Edward Arnold) — commands much more space and attention; on the other end of his phone receiver is Adolf Hitler, his pal, whom we faintly hear shrieking in frenetic German. The other one, Franklin Roosevelt, is heard speaking over the radio and sometimes seen addressing the camera.

We first find the Devil cackling over shots of lightning bolts and documentary evidence of wartime devastation, announced by headlines: “World fronts explode!” “Shanghai smashed!” “Rotterdam destroyed!” “Flames!” and so on. Then we see him seated behind the glass desk in his futurist tycoon’s office, chortling to his sullen, sultry mistress (Vicky Lane), who periodically smokes long cigarettes or pours long drinks of dry ice: “Wonderful, wonderful! The best season I ever had!” A signed photo of Hitler rests on his desk and a black raven is perched directly over it.

Clearly there’s nothing subtle about Inflation, nor was there meant to be. The Chamber of Commerce was undoubtedly perturbed by this punchy expressionist short because Endfield carried out his assigned task — attacking various forms of capitalist greed and selfishness leading to inflation — all too well. It seems relevant that the Devil and a couple of wholesome housewives are both glimpsed at unsettling low angles — the Devil from beneath the surface of his glass desk, the housewives almost from knee level, chatting on a suburban doorstep — and it’s difficult to decide which of these two angles seems more sinister. At the age of 27, Endfield already displayed his singular flair for portraying brutish self-interest in a wholly believable and lucid (if sardonic) manner.

The capitalist selfishness the Devil gleefully encourages begins with the buying binge of factory worker Joe Smith (Horace McNally), who goes with his wife (Esther Williams) on a shopping spree as soon as he collects his paycheck. “You look wonderful,” he says late in the trip when she tries on a fur wrap, to which she replies, “Gee, honey, it took four dresses and a new coat for you to say so.” When the clerk suggests that Joe can buy even more for his wife and himself on credit, there’s a cut to the Devil on the phone beaming, “Well, it’s started, Adolf — a blitz without bullets,” and explaining that with few goods around, price bidding is bound to start soon. Laden with packages, Joe and his wife wind up listening to FDR on a radio in a shop speaking at length about all that should be done: “stabilize prices . . . ration scarce commodities . . . invest in war bonds . . . discourage installment buying,” and so on.

“Look at me — Joe Sap!” a chastened Joe declares at the end of this speech, and his wife agrees that they’ve been “overdoing it.” But all the other citizens in this short remain, more plausibly, unenlightened, whether it’s a chorus girl buying nylons on the black market, a tailor being taught by the Devil how to switch labels on a garment and thereby cheat on price fixing, housewives expounding on the virtues of hoarding and stockpiling, or a fellow in a restaurant being convinced by the Devil to cash in his war bonds and buy an expensive car to improve his image.

“Would you like to join us?” the Devil asks the camera at the end, extolling the virtues of racial superiority before he urges us to buy, “squawk,” be greedy, hoard, etc. “Do these things and oblige my friend” — he points to the phone receiver, affectionately adding “Sieg heil!” — “and your most humble servant.” He cackles some more, and the lightning bolts return, welcoming us all to the impending apocalypse.

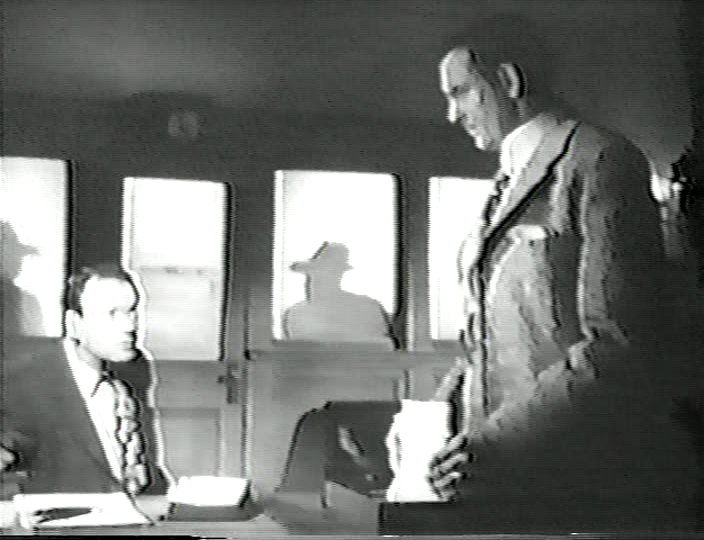

If Inflation is unusually packed and fast-moving, the 63-minute Argyle Secrets is even more so. The cast features well over a dozen fully developed speaking parts, and there are so many interlocking and often paranoid intrigues crammed into one 24-hour story line that I’d defy anyone to come up with a comprehensive synopsis even after a couple of viewings. The sheer darkness of the night scenes only intensifies our occasional perplexity, though it must be added that Endfield and his cinematographer, Mack Stengler, create many remarkable and arresting noir compositions from this interminable stretch of night, usually with what appear to be minimal light sources. (In one scene two figures silhouetted behind frosted glass flank the hero inside a police lieutenant’s office; at the end of the scene, when the hero leaves and the police lieutenant picks up the phone to order two cops to shadow him, the “shadows” promptly disappear from behind the glass.) Another source of overload (however appealingly surreal) is Endfield’s drastic economy: great quantities of plot and deduction are shoehorned into the dialogue or voice-over narration at various junctures.

The story carries certain unmistakable echoes of The Maltese Falcon, made seven years earlier, though the overall brittle, anxious, and doom-ridden mood is even more evocative of Kiss Me Deadly, made seven years later. It seems that the only direct steal in the movie, however, is a shock cut from a character making a belated discovery to a screaming tugboat whistle — Hitchcock in Blackmail gets the same effect from the discovery of a dead body and a train whistle.

Of course the much-sought-after object of The Maltese Falcon is the falcon; in Kiss Me Deadly it’s “the Great Whatsit,” a Pandora’s box that turns out to contain lethal plutonium. In The Argyle Secrets, it’s an argyle album containing the records of certain agreements struck between American and Nazi businessmen during the war, valued as much for its blackmail and resale value as for the journalistic scoop it might provide. As a woman named Marla (Marjorie Lord) explains it, in an expository speech that’s a fair sample of Endfield’s cadenced prose: “You know, some men weren’t so sure we’d win this late and little lamented war. So they made deals, deals with men who should have been their enemies — big money deals so they’d come out all right no matter which side won. The records of those deals were buried deep. What happened? A bomb made a direct hit. A bank vault opened like a spoiled tin can and spilled its rotten secrets. Then came the scavengers, the looters who always follow air raids, and with them Winters, who found among the debris the documents of betrayal. Winters lived in America before, recognized the names inscribed, and knew that he found a fortune — a fortune in blackmail.”

This sort of collaboration with the Nazis is a subject that, to the best of my knowledge, no other moviemakers were broaching in the late 40s; but what is most distinctive about The Argyle Secrets is its view of humanity as inflected by war, a view that seems fully consistent with the one presented in Inflation five years earlier. By the end of the film, even the hero and voice-over narrator — a rather unsavory and callous reporter named Harry Mitchell (William Gargan), who triumphs over all the assorted crooks, creeps, and exploiters in the film through his own cleverness — is more than a little tarnished by his own brutality and careerism, though he claims to have been motivated by loyalty to another journalist. (Eleven years earlier Gargan played Father Dolan in Fritz Lang’s You Only Live Once, which makes him a somewhat unconventional choice for a hero or antihero.)

The other journalist is a famous political columnist, Pierce (George Anderson), who builds up interest in his paper for two weeks about the contents of the argyle album, then offers Mitchell an exclusive interview a few days after he enters a hospital, fearing he might not live long enough to tell his tale. Pierce grows faint and dizzy before he can even explain what the album is, though he does show Mitchell a photostat of its cover; and just after Mitchell rushes to the washroom to fetch him some water Pierce dies, an offscreen death memorably signaled by a close-up of the faucet as it ceases to drip. Mitchell determines that Pierce is dead by feeling his pulse, but moments later, when he returns to the room with several others, they find a scalpel planted in Pierce’s chest. The police turn up, and after the corpse of Mitchell’s photographer is found in the same room only a few moments later, Mitchell flees from the scene, proceeding to Pierce’s office where he promptly (if apologetically) slaps the secretary (Barbara Billingsley) unconscious so he can go through her boss’s address book, hoping to track down the album.

Though he’s far from a nice guy, Mitchell turns out to be relatively charismatic compared with the war profiteers, hoods, and stupid cops — not to mention a corrupt doctor — who figure at various points in the plot, a rogue’s gallery like the one only sketched in Inflation. “Relatively” is the operative term, as it often is in Endfield’s moral universe; when Mitchell learns from Marla that she’s interested in the album only for its resale value he remarks, “That’s a comparatively decent motive,” and she replies, “I’m a comparatively decent person.”

Yet despite the jaded view of human impulses on display here, Endfield doesn’t really qualify as a misanthrope like Stanley Kubrick (another pessimistic disciple of Orson Welles and the 40s noir tradition). One of the most appealing and unexpected interludes in The Argyle Secrets occurs when Mitchell, fleeing down a fire escape from war profiteer Winters (John Banner) and his hoods (who have beaten him senseless offscreen, expressionistically depicted in a sequence that illustrates his delirium), suddenly enters the flat of a working-class Jewish family he knew slightly years before. Much of the scene’s comedy stems from the family’s unobservant, trusting attitude toward Mitchell — a boy (Kenneth Greenwald) dutifully carries out his violin practice under the strict orders of his ditsy, anxious mother (Mary Tarcai) and dim-witted but good-natured older brother (Robert Kelland), a rookie cop who suddenly turns up with groceries.

Though Endfield ribs all three of these quaint, myopic characters, he’s clearly affectionate rather than caustic. (Jewish himself, Endfield suggested to me that he regarded this scene as something of an in-joke about his own early experience, most likely as a magician, in the Catskills — a borscht-circuit background that later led to his staging the English production of Neil Simon’s first play, Come Blow Your Horn.) There’s a similar gentleness in Endfield’s treatment of a stupid police lieutenant (Ralph Byrd), who figures much more prominently in the plot than the Jewish family. And if the “comparatively” decent Marla is still largely a standard-issue noir bitch goddess, the other, more odious types in the story — a southern rascal with a stiletto (Jack Reitzen), a fence whose cover is his job in waterfront salvage (Alex Fraser), and arguably even Winters — offer brief glimpses of humanity. Like the pinpoints of light briefly and strategically illuminating the film’s endless reaches of darkness, these small, humanizing breaks in the overall pattern of greed are glancing yet pivotal elements in the overall composition.