From the Chicago Reader (September 20, 1991); reprinted in Placing Movies. — J.R.

I have noticed that people who were loved or felt they were loved seemed to lead fuller, happier lives. All of my own work in theater and film has been concerned with varying themes of this love.

A Woman of Mystery has to do with an unexplored segment of our society, referred to as the homeless, bag ladies, winos, bums — labels that are much easier for the public to deal with than the individual.

It has been difficult to explore this particular woman of mystery. She is not only homeless (if homeless means without the comfort of love) but she is nameless, without the practical application of social security, or any other identity. Alone, she clings to her baggages on the street.

Our heroine enters into a series of encounters that challenge her isolation, her inability to communicate. A young woman passerby seems to feel that this woman with the suitcases is the reincarnation of her dead mother. An emotional dismissal of the younger woman causes the woman’s memory to play tricks on her. A young man seems to touch unexplained dependency in her and a clerk at a travel bureau gets dangerously close to exchanging love.

Change continues as the woman comes forward, attempting sociability. But, in the end, normal feelings of affection are too difficult to return to. The woman has been permanently disabled by the long discontinuance of feelings of love.

These are John Cassavetes’s program notes to his last realized work — an awesome three-act play starring Gena Rowlands and Carol Kane that he wrote and directed, and that I was lucky enough to see. It was performed in a small theater in Beverly Hills for two weeks during the summer of 1987; considering the size of the auditorium, I can’t imagine many people saw it. It was obviously a production done for love rather than money, and its treatment of the homeless couldn’t be described as an act of either condescension or abstract piety. Terrifyingly human, tragic and mysterious, it revolved around both the heroine’s lost identity — literally, her lack of definition — and the difficulty others, including the audience, had making contact with her. Actual street people — including some musicians, a stand-up comic, and a poet–came onstage and performed during the intermissions, and at no point did the actors seem out of step with them.

Basic questions about love, identity, and definition are at the root of all of Cassavetes’s work as a filmmaker, and it somehow seems appropriate that the sharpest, starkest posing of those questions came at the very beginning and at the very end of his career. In his ground-breaking first feature, Shadows (1959), these questions center on two brothers and a sister who live together in Manhattan. The older brother, a dark-skinned black named Hugh (Hugh Hurd), is the only one of the three who has a pretty clear sense of who he is, even though this happens to be a pretty terrible (though serious) nightclub crooner. His lighter-skinned younger siblings, Ben (Ben Carruthers) and Lelia (Lelia Goldoni), are much less centered, in part because they both “pass” for white; Ben “passes” consciously, Lelia apparently unwittingly, and neither can be said to have a fully fixed identity. After Lelia loses her virginity to a young white seducer, he escorts her home, where he’s taken aback when he sees her greet Hugh as her brother. In one fell swoop her sense of self is devastated by her seducer’s shock and discomfort. Virtually none of this is discussed or “explained” in the dialogue; apart from a fleeting reference by Hugh to “a problem of the races,” the entire drama is played out in the faces and behavior of the actors, with a subtlety and sensitivity that still bring me to tears every time I see the film.

Shadows started out as an improvisation on this scene in Cassavetes’s New York acting workshop. Talk-show host Jean Shepherd happened to be visiting and was so impressed that he invited Cassavetes onto his late-night show, Night People, during which Cassavetes brashly proposed that interested listeners send in one dollar apiece to finance a film; $2,500 was collected within a week. After raising additional funds, Cassavetes shot a free-form, hour-long feature that was screened three times at midnight, for no admission, to about 2,000 people, and that was declared a masterpiece of the “New American Cinema” by critic Jonas Mekas. But Cassavetes failed to find a distributor, so he shot eight additional scenes and edited a new 85-minute version that had more conventional continuity and narrative structure; it opened in 1961 and is the only version of Shadows that survives today (though Mekas, for one, regards it as inferior to the original). The two versions cost a total of $40,000, and together they launched a revolution in American independent film that is still going on.

Lured to Hollywood by a studio contract, Cassavetes directed two more pictures with mixed results, Too Late Blues (1961) and A Child Is Waiting (1963); the second of these was so altered by producer Stanley Kramer that Cassavetes virtually disowned it. Returning to maverick independence with a vengeance, he next made Faces (1968), the success of which led to two more studio deals (Husbands and Minnie and Moskowitz) over which he had full control and final cut. They were followed by three features he distributed himself: A Woman Under the Influence (1975), The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976, rereleased in a shorter version in 1978), and Opening Night (1978); only the first of these was a commercial success — the other two were resounding commercial failures and barely circulated. Then came two features done for other companies, Gloria (1980) and Love Streams (1984), which did somewhat better, but not well enough to finance any more pictures. (An abortive experience taking over the direction of Big Trouble [1986], a comedy that was already in production and was subsequently recut by the producer, doesn’t really qualify as part of the Cassavetes oeuvre.) The remainder of Cassavetes’s “independent” activity was his small-scale theater work in Los Angeles: East/West Game, which he wrote and directed in 1980; three more plays in 1981, two of which were written by Ted Allan (including Love Streams, the basis of Cassavetes’s last film); and A Woman of Mystery in 1987.

Tragically but predictably, now that John Cassavetes is dead it’s become possible, even fashionable, to like his movies again. Indeed, I suspect that the Music Box’s five-week retrospective that starts this week –encompassing all the features Cassavetes owned — will be much better attended than was the Film Center’s retrospective five years ago. With the exception of Love Streams, all of his major works are being shown, and there are no finer works in the American independent narrative cinema.

That this sort of recognition can take place only after Cassavetes’s death means that his work is only a fraction of the size it would have been if critics and audiences had been more attuned to what he was up to. Speaking for myself as well as for most of my colleagues, we were usually wrong about Cassavetes –even when we wrote in support of his work, which was seldom often enough. Admittedly, he didn’t help us out all that much, being one of the least articulate major filmmakers when it came to describing the methodology and meanings of his work; his lack of clarity or eloquence often made him resemble one of his characters. But the task of verbalizing essentially nonverbal film experiences generally defeated us.

We assumed, quite wrongly, that Cassavetes was a primitive realist who depended mainly on improvisation from his actors, but he was neither primitive nor a realist in any usual sense, and most of the dialogue in his movies after Shadows was written by him. We often assumed that the dialogue was improvised because it sounded spontaneous, and we often assumed that the stories and characters were supposed to be “realistic” because the shooting style gave the films a documentary look. These false impressions were undoubtedly furthered by the fact that Shadows declared itself to be an “improvisation” in its final credits (mainly, it seems, because the actors generated most of the dialogue) and aimed for a kind of verisimilitude in relation to its milieu (not always successfully, as an awkwardly conceived “literary” party reveals). In addition, Faces, by concentrating on certain forms of middle-class behavior that had been overlooked by Hollywood — particularly the compulsive laughter that grew out of sexual embarrassment — made it seem realistic to many people when it came out in 1968. Comparable elements cropped up in Husbands, Minnie and Moskowitz, and A Woman Under the Influence, but it can be argued that by the mid-70s Cassavetes had shifted almost entirely into a mythological universe controlled more by notions about genre (The Killing of a Chinese Bookie and Gloria) and personality (Opening Night and Love Streams) than by superficial concerns with social accuracy. Most critics, still stuck in their earlier formulations, tended to be baffled by this development, though a closer look at some of the earlier works might have revealed what was in store.

The central location of Faces — the home of a middle-class couple in a state of crisis — was the house that Cassavetes, Gena Rowlands, and their children lived in; it was used again as the central location in Love Streams. No effort seems to have been made to redecorate or refurnish it to suit the tastes of the middle-class couple in Faces, and nothing about it — neither the art and signed photographs framed on the walls nor the books on the shelves — rings true for these characters. Such indifference to setting is not a virtue, but given the film’s concentration on the actors’ faces, it can’t really be considered a serious flaw; Cassavetes clearly regarded it as irrelevant or at least secondary.

Faces opens with a private screening of a film in the office of the hero (John Marley), an insurance executive, who is surrounded by business associates. The lights in the screening room fade and the credits for Faces appear, implying that these people are watching the movie that follows, a movie about themselves. But the remainder of the film never alludes to this screening, and if we don’t emerge from the film totally confused, we probably conclude that the film the business associates saw wasn’t Faces but an industrial short or some commercial relating to insurance.

The title heroine in the galvanizing A Woman Under the Influence, a working-class housewife and mother played by Gena Rowlands, has a serious nervous breakdown and is committed to an institution for six months. There’s a large party at her house to welcome her back when she’s released, but not once is it suggested that her devoted husband (Peter Falk), their kids, or any of her friends or other relatives has been to visit her during her half year away.

Comparable distractions and irrelevancies crop up in most of the other movies, and they can’t be wished away. But in order to understand what Cassavetes is doing, one has to get beyond them. His cinema is centered almost exclusively on actors and scenes; questions about settings, events and durations between scenes, and most of the other forms of narrative glue and “filling” (or “stuffing”) that we expect from fiction films to establish the characters and their milieus are generally given short shrift. Disdaining exposition, Cassavetes’s movies generally plunge us into the world of their characters without the usual signposts and road maps, forcing us to flounder for a while along with the characters. Existentially speaking, his movies are about what they show and what we see and hear, not about theoretical or actual “background” material that takes place between or beyond the shots. But to accept this principle, we have to adjust the expectations we bring to most films.

Another potential obstacle needs to be brought up. In spite of — or should I say because of? — their radical humanism, Cassavetes’s films are not “politically correct.” According to David E. James in Allegories of Cinema: American Film in the Sixties, the casting of a white actress in the part of Lelia in Shadows constitutes an ethical and aesthetic cop-out that invalidates the drama; given the beauty and power of Lelia Goldoni’s performance, I must confess this argument made me want to throw James’s book against the wall. However, the brutality with which women are often treated in Husbands — which the film’s bullying macho ambience often seems to endorse (or at least tolerate) more than criticize — turned me against Cassavetes for a number of years, and I still haven’t resolved whether this description of the film qualifies as a misreading. (Peter Bogdanovich, for one, has defended Husbands as “the first, and in many ways still the most trenchant and honest, American look at the overwhelming alienation and homelessness which the hypocritical sexual revolution was by then [1970] leaving in its wake.”) Conversely, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, which I’ve always cherished as Cassavetes’s testament –an ironic self-portrait starring Ben Gazzara as Cosmo Vitelli, the pathetic, lamebrained, and defeated (yet indefatigably stylish, courageous, and noble) owner of a Los Angeles strip joint — has been denounced by a feminist friend of mine as the worst kind of patriarchal and sexist sentimental slop. And from the point of view of political correctness, I suppose she could be right. I doubt, however, that she could make the same argument about Gloria — a joyously subversive reworking of the gangster film that is arguably as feminist as Thelma and Louise (only Gloria and Love Streams are available on video).

If, however, we consider the stranglehold that “political correctness” of various persuasions currently has on the media — fostering attitudes that would probably make a movie like Shadows impossible to finance today — I think Cassavetes’s work warrants a closer look. The complete absence of villains and the touching celebration of various kinds of human sweetness and affection — exemplified by such wonderful characters as Hugh’s manager (Rupert Crosse) in Shadows, a disco hustler (Seymour Cassel) in Faces, and even Cosmo Vitelli in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie — has a great deal to do with what keeps his films vital and powerful. If Cassavetes’s radical humanism challenges some of our cherished notions about appropriate role models, perhaps that challenge makes it even more valuable in the long run. For all their hectoring anti-intellectualism, his movies are frequently object lessons in how we might behave more decently and caringly toward one another. (I first discovered Shadows when I was a high school senior who had been reading J.D. Salinger’s Glass family stories, and it struck me then — as it does today, having seen Shadows perhaps a dozen times since — that the interactions between the siblings in Cassavetes’s story are far warmer than those between Salinger’s family of elitists, whose love always seemed predicated on principles of snobbish exclusion.)

While Cassavetes has been one of the most influential of all American independents — having marked the works of directors as different as Bogdanovich, Jean Eustache, Jean-Luc Godard (who has dedicated two works to him), Henry Jaglom, Elaine May, Rob Nilsson, Maurice Pialat, Jacques Rivette, and Martin Scorsese, among many others — I can think of only one other American independent writer-director-actor who is conceptually comparable to him: Orson Welles. Considering the extreme disparity between these directors in terms of visual and cultural style, a connection may seem unlikely, but it actually runs quite deep. And it isn’t surprising to hear that Welles and Cassavetes were great admirers of each other’s work.

Having just completed the editing for publication of a book-length interview with Welles, I’ve been struck by the degree to which Welles considered the actor rather than the director to be the key figure in filmmaking — an attitude Cassavetes clearly shared. It might even be said that “acting” was the subject of all of their films — not merely because of their passionate interest in actors, but also because their view of human nature and behavior had a lot to do with performance and the notion that everyone is an actor. (Both directors often recruited their actors from highly unlikely places. The extraordinary Lynn Carlin, for example, was working as a secretary for the then-unknown Robert Altman — and had been hired briefly to type the original script of Faces — when Cassavetes recruited her to be the film’s lead.)

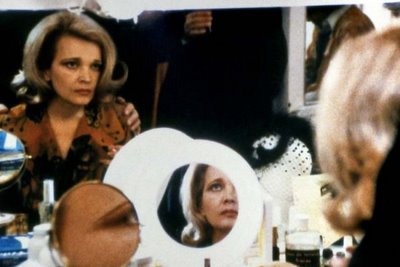

For Cassavetes, acting is merely a heightened form of the social activity we all pursue in our various transactions with the world. This idea is the literal concern of Opening Night, which focuses on the crises experienced by a troubled stage actress (Gena Rowlands) and the other actors (including Cassavetes) she performs with; but it’s no less important in the role-playing highlighted in his other films. Consider the carefully manufactured facades of most of the leading characters in Shadows, Faces, A Woman Under the Influence (especially the title heroine), and The Killing of a Chinese Bookie — and the confusions and clarifications about their identities that arise when those facades are chipped away–and you have the essential subjects of all four films.

The martyrdom of Cassavetes — like that of Welles before him — seems to be the obligatory price exacted in this country for working outside the methods and assumptions of the industry. (Both directors, significantly, have received much more recognition for their independent efforts abroad than in this country.) This martyrdom also has something to do with the “scandal” of caring more about the work itself than about the financial reward to be gained from it. What probably elicited the most scorn in Hollywood, where both men lived, was their willingness to subsidize their own low-budget productions with the money made from their more routine work as actors–something both were usually forced to do in order to make movies at all.

We’re still living with the legacy of that martyrdom, and it’s difficult to calculate the size of our loss. (What kind of film culture would we have today if we had as many movies by Welles and Cassavetes as we have by Woody Allen? The very notion staggers the imagination.) Fortunately, the size and power of what we have is still enormous. And now that we have the evidence of Cassavetes’s genius again before us — films that have far too long been unavailable and neglected — we owe it to ourselves to discover what his art and vision were all about.