From the Chicago Reader (May 7, 1993). — J.R.

DAVE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Ivan Reitman

Written by Gary Ross

With Kevin Kline, Sigourney Weaver, Frank Langella, Kevin Dunn, Ving Rhames, and Ben Kingsley

SILVERLAKE LIFE: THE VIEW FROM HERE

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Tom Joslin and Peter Friedman

With Tom Joslin, Mark Massi, Charles and Mary Joslin, Whitey and Sue Joslin, and Lois Black Hill.

Is it the prime purpose of every movie we want to see to tell us comforting lies? On some level I suspect it is, and paradoxically this may be the case even with pictures that supposedly break through reassuring deceptions to give us the unvarnished truth. One way or another, even the best of films tend to deceive us about certain matters — and if they didn’t, we probably wouldn’t give them the time of day.

The two recent examples I have in mind are in other respects about as different as movies can be. With a skillful piece of Hollywood pastry like Dave, an Ivan Reitman comedy about a small-time businessman named Dave (Kevin Kline) impersonating the U.S. president (Kline as well), one might at first be drawn in by its refreshing candor about the ignobility of the office of president. Contrary to appearances, we’re quickly informed, presidents are not really the source of most national policy decisions. The movie can come up with only one actual source, however — an unambiguously evil chief of staff, played by Frank Langella in his ripest fanged manner, who appears to represent no one but himself. A stand-in for the ultrarich? No, not even that; all that apparently motivates Langella’s Bob Alexander is an unexplained and, under the circumstances, inexplicable desire to take over the Oval Office officially.

Combining some of the root assumptions of Frank Capra — in particular, some of the kernels of pseudo folk wisdom associated with messieurs Deeds, Smith, Doe, and Bailey — with the megalomaniacal pleasures of Charlie Chaplin in The Great Dictator, Dave revels in such charming effects as showing what it might be like to be president and have a take-out deli dinner with the First Lady (Sigourney Weaver) in a Washington park. The operator of a small temporary employment agency in Baltimore, Dave is enlisted by Alexander to impersonate the president to allow the crooked original more time for illicit sex. When the real president has a sex-induced stroke, Dave is asked to take over the job on longer-range terms, operating under Alexander’s thumb.

At first Dave is too awed by his surroundings to question the decisions being made. (While being shown the president’s press-briefing room, he’s preoccupied about whether he can keep a souvenir ballpoint pen.) Eventually, though, Dave sees the light, and after quickly acquainting himself with the country’s major problems and their solutions in one extended work session with a Baltimore chum (Charles Grodin at his funniest), he defies Alexander and takes over the decision making. And to make sure we don’t think Dave’s simply a bleeding heart or a goody two-shoes for wanting to help the homeless and the unemployed — a problem Capra, living in a less cynical era, would never have had — the script takes care to clarify that Dave’s real motive is to win back the humanitarian First Lady, whom the real president alienated long before, so he can climb into bed with her.

As nonsensical as all of this sounds, the movie does a nice job of putting it across by making these mystifications cozy and comforting — even tinged with some nostalgia for old Hollywood despite the cynicism. To a very large extent it does this by using not only real locations (or convincing facsimiles) but real Washington types and media personalities — that is, everyone from Paul Simon to Oliver Stone, by way of Jay Leno and Larry King — to spice up the proceedings. Ten years ago, in the purely literary and allegorical Zelig, Woody Allen made comparable use of Jewish intellectuals like Saul Bellow, Irving Howe, and Susan Sontag; and here, as in that film, the “authentification” imparted by these individuals ultimately backfires. If their presence initially makes the movie more “believable,” later it tarnishes our sense of their believability: if they’ve lulled us into accepting a falsehood this time, how far can we trust them on other occasions? Like Reagan’s scorched-earth economic policies, this movie relies on the kind of verisimilitude that simply serves its purpose and then is gone, and never mind who or what gets wasted in the process — all, to be sure, in the spirit of good-natured fun.

***

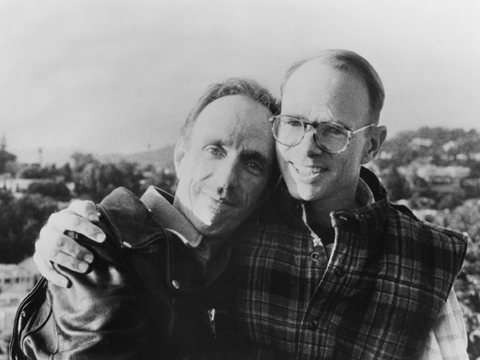

It’s obviously a shotgun marriage of sorts to juxtapose Dave with Silverlake Life: The View From Here. This deeply affecting video diary transferred to film (showing at the Film Center Monday, next Thursday, and Saturday, May 22) records the slow deaths by AIDS of a filmmaker and his lover of 22 years. In this film, telling the truth clearly has a special kind of urgency. Started by filmmaker Tom Joslin and completed after his death (according to a prior agreement) by his friend and former student Peter Friedman, the film seems motivated above all by the public’s sheer denial of the events and subjects it depicts.

Because of this denial, it becomes very difficult to approach a film like this without prejudging it; criticism, one is made to feel, is a luxury next to the brute fact of such a work’s existence. Even apart from the issue of AIDS, which shouldn’t be underestimated, real death (as opposed to movie death) remains such a fearful taboo in our society that it becomes almost impossible to approach a film like Silverlake Life without somewhat hysterical expectations. I knew that I wanted to see the film as a reviewer, but at the same time my limited knowledge of how it dealt with its subject matter made me reluctant to preview it. So I can readily understand other viewers feeling apprehensive. A superficial account of the film might make it sound a monstrous and unnecessary act of self-indulgence, when in many respects it is anything but that.

I hope our guilt and fearfulness about AIDS won’t reduce this film to a mere rallying cry — a very real danger in a culture that often takes its cues from the movies. Americans were unwilling to seriously discuss an issue like John F. Kennedy’s assassination until a joker like Oliver Stone (one of the authenticators in Dave) made a movie about it. Indeed, considering that the press actually took seriously the burning issue of whether or not to commit a night of adultery for a million dollars — an “issue” that would never have been entertained for an instant at any other time, or for any other reason than selling a Sherry Lansing stinker — the likelihood of Silverlake Life being addressed on its own merits seems very small indeed.

But these are merits well worth attending to. The film shared (with the relatively conventional Children of Fate) a grand jury prize for best documentary at the last Sundance film festival and received the Playboy Foundation’s first Freedom of Expression award. Nevertheless it was rejected by at least a couple of prominent New York theatrical venues before being unexpectedly scheduled for broadcast by PBS. I hope it gets seen, one way or another, though its very real achievement as a film isn’t merely the tragic and tender love story it tells but also its concentrated, efficient form: this highly constructed narrative gains much of its power from what it omits.

This isn’t to accuse Silverlake Life of any kind of dishonesty. Any direct depiction of death in a documentary tends to both overwhelm all its other qualities and necessitate certain omissions and abridgements in order to deal with the subject at all. Despite the film’s apparent aim to show us “everything” and spare us “nothing,” the most moving aspect for me — and the factor that finally makes the film accessible — is its sense of privacy, the implied collective weight of all that it refuses or simply neglects to show us about Tom Joslin and Mark Massi. Without that reticence and missing material — including such information as what brought and kept them together for over two decades, as well as what might have precipitated their illness — watching such a film might have been merely a form of punishment for the audience, a guilt-ridden civic duty to see what we don’t want to see. Instead, it celebrates a particular relationship and offers a passing glimpse of a particular milieu (the Silverlake district of Hollywood, though there are a couple of side trips to New Hampshire) and some wisdom about ways of coping with death. I wouldn’t want to claim that the film is easy to take, but neither are its virtues simply the negative ones of taboo breaking. At its best, it offers a way of looking at the world that concretely suggests — even to some extent requires — rejecting its present moral priorities.

If Dave employs pseudo-documentary trimmings to maintain some credibility, Silverlake Life gets a comparable effect early on by alluding to “the movies,” when Mark speaks to the camera about trying unsuccessfully to close Tom’s eyes after he died. “I apologized to him,” he says. “Life wasn’t like the movies.” (He provides similar saving bits of wry humor throughout the film, even when he’s placing Tom’s ashes in an urn.)

In classic movie form, most of the remainder of the story comes in flashbacks, and significantly the film is framed by two declarations of love. In the first Tom announces that this is both the first take of Silverlake Life and a message to Mark, and he looks through a cutout in the shape of a heart surrounded by the words “Mark I love you.” The last comes in a clip from a documentary Joslin made 15 years earlier — Blackstar: Autobiography of a Close Friend, a film about his coming out — that shows him dancing with Mark to “I Met Him on a Monday” and ends with them kissing.

What isn’t explained in the film — it would have been impossibly complicated to do so — is that Joslin started Silverlake Life as a series of short pieces about Massi and Massi’s illness when he thought that his lover would be the first to die. Then, as Joslin’s own illness grew worse, Massi took over more and more of the filming himself, and Friedman stepped in to complete the work five months after Joslin’s death. Thus the film is a kind of round-robin of mutual regard — each lover as seen by the other, and ultimately both as seen by Friedman. Paradoxically yet vitally, the act of filming becomes not merely an act of witness but an anchor of meaning, and perhaps for this very reason necessitates the kind of focus and discipline that makes some forms of courage and nobility possible.

Along the way we learn a great deal about how the world outside copes, or more often fails to cope, with this ailing couple — especially Joslin’s parents, brother, and sister-in-law, but also Massi’s estranged father, whose sole letter to his son Massi reads toward the end. We also learn about such practical matters as AIDS patients sustaining their energy and exposing or not exposing their Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, witness various kinds of conventional and new-age therapy, and eventually learn how Joslin’s death alters Massi’s convictions about mortality. Through it all, what impresses one most is the film’s economy, as the diminishing energies of both men translate into a necessity for saying and doing things as simply as possible — a limitation that finally becomes a kind of strength, evident in Friedman’s editing as well as in the filming by various hands. Thanks to this unity of purpose, “the view from here” becomes not a distancing frame for a voyeuristic peek but a route to the other side: we sense the people in this movie looking intently at us.