From Film Society Review (Vol. 4, No. 2, 1968), the first film magazine I ever wrote for. The was the second of my three pieces for them. -– J.R.

Godard: Cities and Carwrecks

By Jon Rosenbaum

***

“The impact of progress turns Reason into submission

to the facts of life, and to the dynamic capability of

producing more and bigger facts of the same sort of life.”

— Herbert Marcuse, ONE DIMENSIONAL MAN

***

“A heaving sea of air hammers in the purple brown dusk

tainted with rotten metal smell of sewergas . . . young

worker faces vibrating out of focus in yellow halos of

carbide lanterns. . . broken pipes exposed. . . .”

“They are rebuilding the City.”

Lee nodded absently. . . . “Yes… Always . . .”

— William S. Burroughs, NAKED LUNCH

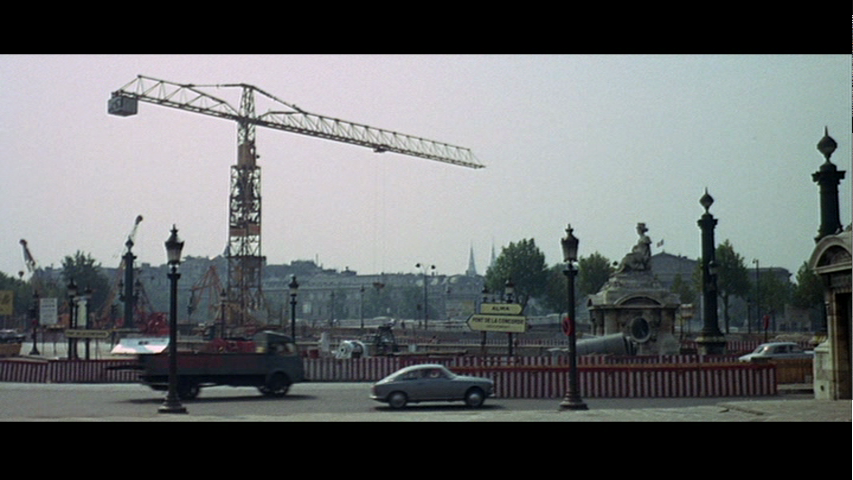

In Godard’s 2 OU 3 CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D’ELLE, Paris is shown and described undergoing a series of strange mutations. One of the most evident of these changes is the monstrous high-rise housing complexes that are being put up in the suburbs, la région Parisienne (the “elle” of the title). Certain housewives living in these new acres of concrete, in order to help ‘make ends meet,’ spend their afternoons in the city as part-time prostitutes.

These ‘facts of life’ are the film’s point of departure. Behind the brief tricolored title credits, one can already hear the harsh, nerve-wracking sounds of a building crew that are to recur frequently throughout the film. Then, dialectically, the first shot shows us an aerial view of a construction site accompanied by dead silence. Presently we hear the off-screen voice of Godard, addressing us in a confidential whisper about la région Parisienne. Soon afterwards we are introduced to Juliette, a local housewife who is to be followed (like Charlotte in LA FEMME MARIÉE) through a typical, plotless day, But by introducing her first as Marina Vlady, actress, Godard makes it {ear at the outset that Juliette’s existence as a character is little more than perfunctory. His primary emphasis here is documentary, just as LA CHINOISE, his next film, is weighted towards theatre (with its political skits, recitations and ‘offstage’ murder). Consequently, the movements and lines of an actress interest him only at a visual subject and a pretext for the commentary; indeed, many of Marina-Juliette’s soliloquies are virtually extensions and relocations of Godard’s narration. The true protagonist of 2 .OU 3 CHOSES is Godard himself, as he appears to us on the soundtrack — the catalyst and conscience that guides us through the film, questioning, explaining, qualifying and transcending what he shows us.

Godard has pointed out that 2 OU 3 CHOSES “is not a film, it’s an attempt at film, presented as such and actually forming a part of my own personal research.” The procedure of this desperate search is not so much to test ideas as to quickly run through them, in effect use them up — a method represented in the film, at the point of self-parody, by the brief appearance of Bouvard and Pecuchet in a cafe, speedily reeling off and copying down random passages from an endless pile of books. As Godard’s ultimate confrontation with his own materials, methods and purposes, 2 OU 3 CHOSES is easily the most ambitious, analytical and personally direct of his creations so far, but by its own premises it cannot be called the most ‘successful’ or complete (a status I would reserve for LE MÉPRIS). To some extent, it shares with his confession in LOIN DE VIETNAM the painful task of enunciating a stalemate: the deadlock between what he would like to film and what he is able to. Consequently, his concern hers is ‘research’ rather than results, and a growing tendency to think in terms of short units — shots and sequences rather than sustained ‘statements’ — has been indulged to such a degree that the film often threatens to become an anthology of documentary methods. In this respect, it strongly resembles James Agee’s beautiful and exasperating book about Alabama sharecroppers in the 30’s, LET US NOW PRAISE FAMOUS MEN, a similarly personal and anguished work that intermittently annihilates its subject in the search for a pure and truthful language. Language, Juliette tells her young son, is the house that man lives in; and it is Godard’s dogged search for a ‘house’ in which he can live –along with a commentary on Juliette’s life — that provides the film’s continuity.

Not surprisingly, the rich mosaic through which these concerns are threaded is uneven, erratic, and for the most part dramatically non-cumulative; in the final words of the film, “since one is brought back to zero, it is from there that one must start again.” Yet some of the parts of this mosaic are among the most extraordinary achievements in Godard’s career:

In one lengthy virtuoso take, we are offered a prime instance of on of the most disturbing techniques in his repertoire — the gag rendered as nightmare: the camera follows the movements of a baby-sitter that Juliette leaves her daughter with for the day — an old man who uses his flat as a combined nursery and brothel — as he busily officiates over his dual interests; then blithely turns to gaze out the window just as Juliette passes by below (having just left the building), while we continue to hear her daughter crying hopelessly, inconsolably, inside the flat. Later on, in a cafe, the camera bypasses Juliette completely to focus on enormous close-ups of a cup of black coffee, filling the entire Cinemascope screen with a sensual immediacy that turns the coffee into a swirling, exploding universe, progressively modified by the passionate, seemingly unrelated commentary of Godard that accompanies it: two wholly independent statements merge in a fugue of breathtaking beauty. In a later sequence, when Juliette goes to see her husband in the garage where he works, the scene becomes the occasion tor rapidly fragmented montage and darting probes of the camera that decompose, rearrange and deflect the separate events (at one point, turning leaves reflected on the hood of Juliette’s red convertible into an impressionist painting), while on the soundtrack Godard asks himself an endless barrage of questions:

“. . . Is it right that I use these words and these images? Are

they the only ones? Aren’t there others? Am I speaking

too loudly? Am I too far away or too close? . . . By the image,

everything is permitted. The best and the worst. . . . Objects

exist, and if we take better care of them than of people,

it’s because they exist that much more than people. . . .

It’s 4 :45 p. m. Should I speak of Juliette or of the leaves?

Since it’s impossible, in any case, to say two things at once

…let us say that both tremble gently at the end of an

October afternoon.”

Like L’ANNEE DERNIERE A MARIENBAD and PARIS NOUS APPARTIENT, 2 OU 3 CHOSES emerges as a rigidly anti-thesis film, a work that continually and systematically undermines its own metaphysics. Yet somehow, an austere, almost Langian concept of the city and its victims is finally conveyed — one that reaches past the modern mausoleums of ALPHAVILLE towards the pastel-plastic idiocy of the settings of Jacques Tati’s PLAY TIME, another extraordinary film that deals with contemporary Paris both as abstract idea and as (reinforced) concrete reality. One comes away from the film with the sense of a noble, cosmic vision of man’s capabilities that, while never being fully articulated, is implicit in the film’s ‘research’: a vision that (again like Tati’s) is curiously set off by the architectural monstrosities that contain it. It is in the context of this vision that we can appreciate the real value of Godard’s ‘uncertainty’ — which, needless to say, is only the other side of his formidable honesty.

Since Godard’s films portray contemporary life both as a void (making it necessary to “start from zero”) and as space cluttered with gratuitous objects — the commercial artifacts of industrial society — it is appropriate that WEEKEND announces itself in separate titles: “A film gone astray in the cosmos;” “A film found on the scrap heap.”

Whichever title is more representative of the film — and how can we choose between them if Godard himself cannot? — the focus of WEEK END is both wider (in terms of characters and locales) and narrower (conceptually) than that of 2 OU 3 CHOSES. This is not to suggest that WEEK END’s conception is narrow in its effects and implications; only that, by giving possible answers to some of the earlier film’s questions (Are these the words and images to use? Are they the only ones?), it is naturally less open-ended. In more ways than one, we’re back to the simple, fable-structured metaphysics of LES CARABINIERS, where every action is made part of a greater necessity. These are the words and images used, the film proclaims, and they are the only ones; one is challenged to accept them in toto, or not at all.

Put more bluntly, WEEKEND is a shocker. Following the petty exploits of a vicious bourgeois couple, Corinne and Roland, on a trip to the country, the film moves through a tortured landscape of corpses, burning carwrecks and savage antagonisms that culminate in ever-increasing crescendos of horror.

An attempted synopsis, much-abbreviated: 1) In the city, Corinne and Roland are each plotting with separate lovers to bump off the other; together they discuss their long-range project of poisoning Corinne’s father for an inheritance; Corinne relates to her lover a deadpan account of a three-way orgy she recently participated in, involving (among other things) eggs, wine, defecation, a bowl of milk and the kitchen sink. 2) On their way to the country, Corinne and Roland encounter a noisy traffic jam (rendered in an excruciating tracking shot that lasts over seven minutes); pass a screaming match between a farmer and a girl whose wealthy boyfriend has just perished in a collision between his convertible and the farmer’s tractor (“I’ve had the right of way, and now he’s dead!”); are hijacked momentarily by a hippy miracle-maker, Joseph Balsamo. 3) After pushing a bicyclist, motorist and pedestrian off the road, their car is demolished in an apocalyptic pile-up (blood-curdling screams from Corinne: “My Hermes pocketbook!”) 4) On foot, they encounter a number of picaresque characters including St. Just; Gros Poucet and Emily Bronte (the latter burnt to a crisp by Roland, in a fit of pique); Paul Gégauff, a pianist who performs Mozart to a farmyard audience; Jean-Claude Guilbert (a memorable actor in the last two Bresson films who appears briefly to rape Corinne while Roland, bored, smokes a cigarette); and two garbage men, Negro and Algerian, who expound on the revolutionary strategies of the Third World. 5) Arriving at their destination, they find that Corinne’s father has died, and promptly slaughter the mother for the inheritance. 6) Soon afterwards they are kidnapped by a tribe of guerilla hippies living in the woods, some of whose pastimes and rituals are observed (including the cannibalistic ‘preparation’ of a captured girl, with eggs broken between her thighs, which recalls Corinne’s recounted orgy); Roland, trying to escape, is killed; and in the final shot Corinne, now part of the tribe, is munching appreciatively on a cooked piece of him mixed with pork and English tourist. All in all, a pretty swinging affair.

Obviously we have travelled pretty far from the tone and texture of 2 OU 3 CHOSES; yet from a political standpoint, the visions of the two films can be seen as somewhat complementary. lf 2 OU 3 CHOSES shows us what prisons (economic, social and architectural) look like from the outside, WEEKEND gives us a horrifying view of their interiors. The metaphors have changed, of course; the prisons in WEEK END are represented mainly by the cars. And some wholly fresh points have emerged: there is little in 2 OU 3 CHOSES, for example, to suggest the mutual antagonism and/or indifference between classes that comes out in the scene of the car-and-tractor collision. (A reality cruelly underscored by crosscuts to a man giggling nearby, and later to a mock group portrait of everyone in the immediate vicinity, in apparent union; the shot is prefigured by the snide title, “Fauxtographie”.) But much of the essential nature of the protest remains the same.

An even greater difference is felt in the absence of a commentary (unless one counts a few editorializing flash titles); but Godard’s ‘conscience’ is nonetheless manifested in a number of ways, in characters like Emily Bronte and Gros Poucet; in Paul Gégauff, whose concert and audience, embraced in liquid 360-degree pans, supply some of the few calm moments in the film; and (a bit stodgily) in the political monologues of the garbage men. Most of all, one senses Godard’s presence in Joseph Balsamo, who (significantly) provides Corinne and Roland with their first real adventure on the road. After getting his girl friend to flag them down, he orders them at gunpoint to drive to Mantes-la-Jolie; a flash title presents him as THE EXTERMINATING ANGEL; next we see him taking photos of the couple, explaining that he’s “Minister of the Interior,” here to reintroduce “flamboyance in all things, particularly the cinema.” Then he asks to be taken to London (perhaps so he can make ONE PLUS ONE there with the Rolling Stones?), promising the couple anything they want in return; a bona fide magician, he demonstrates his power by producing a rabbit from the glove compartment (a trick any film director can do). Convinced, the couple express their deepest desires — a hotel in Miami Beach, naturally blond hair, a weekend with James Bond. Balsamo leaves them in disgust, but not before yelling “Silence!” — like Fritz Lang at the end of LE MÉPRIS — and turning a field of carwrecks into a flock of sheep.

In short, Godard’s role in WEEK END is that of magician and fairy-tale spinner (admittedly closer to the Brothers Grimm variety than to Andersen)’But it should be pointed out that some of his tales are twice-told; throughout the film, numerous echoes are evoked or suggested. The murder of Corinne’s mother is patterned after a shot in PSYCHO; immediately afterwards, MONSIEUR VERDOUX is alluded to (another film which equates murder with capitalism); Truffaut’s FAHRENHEIT 451 is recalled often, particularly in the disturbing, lingered-over plastic beauty of the fires. (Roland setting fire to Emily Bronte is shown as a kind of tragic book-burning; when Corinne protests, he explains that “she’s only an imaginary character”. “Then why is she crying?” Corinne asks. One might add that Godard’s romantic inclination towards lyrical hysteria, prevalent also in PIERROT LE FOU and MADE IN USA (both in color and both bringing to mind action paintings in blood), explains part of his welt-advertised debts to Nicholas Ray and Samuel Fuller (similarly violent and moralistic directors).

The point of this list is not how much Godard steals, but rather the extent to which he adapts and transforms (i.e., uses creatively) the work of other artists. (One could make up another long list of the writers in WEEK END; and the use of Mozart — like the use of Beethoven in 2 OU 3 CHOSES — is certainly original.) Paradoxically, his modernism (like Joyce’s, Eliot’s and Pound’s) is partially based on his adherence to tradition’ But like these earlier figures, his use of tradition is creative because he goes to the trouble of rediscovering it -– re-evaluating and revitalizing the past of an art that is just becoming old enough to have a history. At the age of 38, with sixteen feature films and about a dozen sketches to his credit, Godard still has a long way to travel; the unevenness and instability of his oeuvre-which is still (fortunately) being redefined with each new work — leaves a lot of-questions yet to be answered. In the meantime, 2 0U 3 CHOSES and WEEK END are major events to contend with.