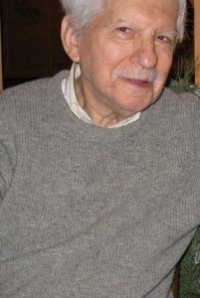

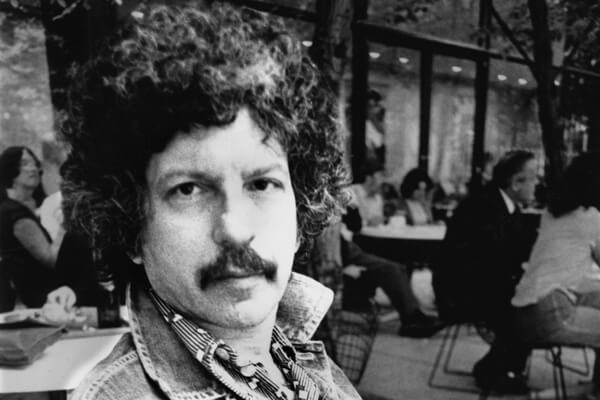

I can’t remember precisely when it was that I first met Elliott in Paris, but I’m sure it was in the early 70s, and I suspect it was the late Carlos Clarens, another Cinematheque regular, who introduced us, most likely after some Palais de Chaillot screening. It wasn’t much later when I discovered we were neighbors living a few blocks apart — me in a small, sunless flat on Rue Mazarine, Elliott in a large room stuffed with all sorts of arcane memorabilia at the Hotel de Verneuil on Rue de Verneuil. He was already a pack-rat then, especially when it came to his collection of clippings, and he continued to live that way years later when he eventually moved back to New York — first to a hotel on lower 5th Avenue, then to a roomy loft in Soho on West Broadway. It was a tragic moment for him when he had to move out of the latter place, leaving behind or giving up many of his treasured possessions (including, as I recall, a table once owned by Robert Ryan). And only a few days ago, at the Viennale, hearing about the ravages of Sandy on New York and environs, my friends and I were concerned about whether or not Elliott was okay.

He was special, as I discovered as soon as I got to know him roughly 40 years ago: a wonderfully erudite gossip and knowledgeable critic-historian-buff with enormous funds of information about all sorts of things other than cinema. On Matt Singer’s blog about him at Criticwire, a sweet tribute by his chums at BAMcinématek correctly points out that he was a major resource for Susan Sontag’s ” Notes on Camp,” and remained a good friend of Susan’s for several decades. The fact that he was also something of an outspoken, card-carrying sadist with a special interest in horror movies, however off-putting at first, was immediately offset by his warmth and humanity. He basically maintained that nothing human was alien to him. Even when it came to his underground aesthetics and erotics, he was no sort of ideologue but someone who looked at the world squarely, evenly, compassionately, with a great deal of sympathetic understanding. He also had uncommon gifts as a writer, as I already knew before getting to know him in Paris, especially from his pieces in Sight and Sound. (I treasure his wonderful and highly personal reviews of the autobiographies of Capra and Sternberg, as well as his early appreciation of Gertrud and his detailed report on the scandal surrounding Rivette’s La réligieuse) — not to mention a memorable and creepy early short story of his that had appeared in either New World Writing or Discovery, I forget which. And his monumental essay “My Life with Kong,” which appeared years later in the February 24, 1977 issue of Rolling Stone, had impressed me so much that I wanted to include it in my first book, a personal memoir (Moving Places: A Life at the Movies, 1980), as one of the four pieces by other writers to be included (along with Charles Eckert’s “The Carole Lombard in Macy’s Window” from the Winter 1978 Quarterly Review of Film Studies and two short stories, Delmore Schwartz’s “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” and Thomas Pynchon’s “The Secret Integration”), until my editor at Harper & Row talked me out of it.

A funny yet sad coincidence: the day after I received a Blu-Ray of André de Toth’s fine Western, Ramrod (1947), from Olive Films, I learned not only of Elliott’s death, but also that he had introduced the film at BAM, along with his friend Howard Mandelbaum, about a month earlier. Which suggests that we all need to look at Ramrod again, in tribute to Elliott. (11/9/12)