On October 14, 2012 I received the sad news from Pierre Bayle d’Autrange that his longtime partner Eduardo de Gregorio, also a longtime friend of mine (since 1973), died Saturday night at the St. Louis Hospital in Paris, not long after his 70th birthday.

I wrote the following for the festival catalogue of the Buenos Aires Festival of Independent Film in 2004, to accompany a retrospective of Eduardo’s films — as far as I know, the only such retrospective that was ever held. It is also reprinted — along with a short essay of the same length on Sara Driver (also the subject of a BAFICI retrospective that year)– in “Two Neglected Filmmakers,” a piece included in my most recent collection, Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia as well as here. — J.R.

Eduardo de Gregorio’s Dream Door

It must be a bummer to be an Argentinian writer and/or filmmaker and constantly get linked to Jorge Luis Borges. It must be especially hard if you’re Eduardo de Gregorio, whose first major screen credit is on an adaptation of “Theme of the Traitor and Hero” for Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1970 feature The Spider’s Strategm.

I don’t mean to question the credentials of de Gregorio as a onetime student of Borges — just the appropriateness of a too-narrow understanding to impose on a singular body of work that owes as much to cinematic references as to literary ones, and one that indeed juxtaposes the two almost as freely as it juxtaposes different languages and historical periods (while including all the cultural baggage that comes with each of them). For if we agree with historian Eric Hobsbawm that the overall development from the 19th century to the 20th and then to the 21st is a gradual slide from civilization to barbarism, I believe we’ve arguably accepted not only an operating hypothesis of Argentinian culture in general and of Borges’ work in particular, both steeped in a particular kind of cultural nostalgia, but one of the most precious legacies of both. And considering how roomy the 19th century is, it’s obviously a resource that can be put to radically different uses.

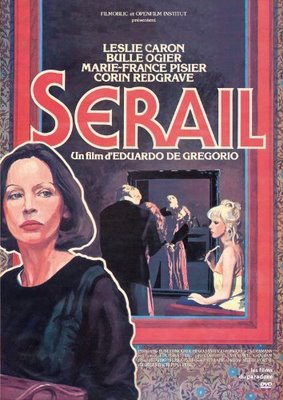

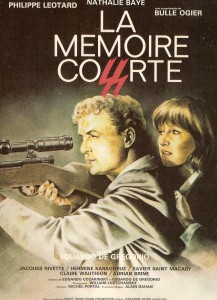

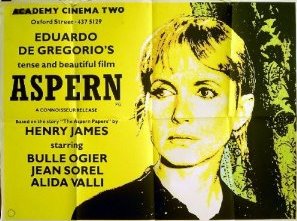

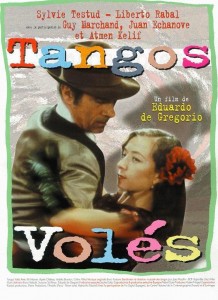

In the case of de Gregorio’s features and his participation as a writer in the elaboration of a few others, the literary tradition most in play is probably the Gothic — and especially one of the principal sites of that tradition, the Old Dark House, which crops up directly in The Spider’s Strategm (where it’s also known as Tara), Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974), Sérail (Surreal Estate, 1976; see three photos above), Aspern (1984, see first photo below), Corps perdus (1989), and, more metaphorically, in my two favorites of de Gregorio’s own features, La mémoire courte (1979) and Tangos volés (2001, see second photo below). (In the heavy Langian menace of the former, it’s the tainted history of Nazism, functioning like an active form of decay inside a film noir in color; in the light, Renoiresque affection and swarming activity of the latter — appropriately overseen by a character named Octave, recalling Renoir’s own character in La règle du jeu — it’s the “old bright house” of a film studio.)

From another point of view, these houses in de Gregorio’s films function in much the same way as manuscripts, paintings, and films — as time machines that are also thresholds into alternate realities, which in Borgesian terms might be described as alternate fictions. For it’s important to recognize that what we call “reality” in de Gregorio’s universe is most often a matter of dialectical fictions: two scheming sexpots (Bulle Ogier and Marie France Pisier — whether they’re competing in Céline et Julie’s film-within-a-film or working in tandem in Sérail); the separate interests of art and commerce (in Sérail, Aspern, and Corps perdus); juxtapositions of the Anglo-American 19th century (via references to Collins, James, Poe, Stevenson, et al.) with the continental European or South American 20th — indeed, nearly always two or more separate national cultures interfacing and interacting across separate time frames and historical periods.

Basically a filmmaker of the fantastique — even when he’s rummaging around in a reasonable facsimile of real history in Aspern and an even more persuasive (if chilling) version of real history and politics in La mémoire courte —- de Gregorio also participated in generating the other-worldly fantasies of Rivette’s Céline and Julie, Duelle, Noroît, and Merry-Go-Round (as well as the history of Jean-Louis Comolli’s 1975 La Cecilia), only the first of which is playing in this retrospective. All of these share with most of de Gregorio’s own features a universe where women, many of them divas, are often the ones in control. What they don’t share are the conniving and cynical men who try to deceive and outwit them — i.e., the heroes of Sérail, Aspern, and Corps perdus, played respectively by Corin Redgrave, Jean Sorel, and Tchéky Karyo. One thing that’s especially likable about Tangos volés — a film whose conscious influences include Hellzapoppin and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty — is the relative lack of malice in the male characters (played by, among others, Liberto Rabal, grandson of Francisco; Guy Marchand; Juan Echanove as Octave; and a little boy who irresistibly recalls Michael Chaplin in A King in New York) — although de Gregorio’s caustic wit is not entirely absent from his treatment of tangomania.

I’d like to conclude by citing a few other insufficiently recognized treasures in his work. There’s the only real performance as an actor (as opposed to cameo appearance) of Jacques Rivette, in La mémoire courte [Short Memory, see above photos] — which, combined with William Lubtchansky’s ravishing color cinematography and the paranoid intensity of the multinational script, makes this film, along with early Robert Kramer, one of the only true successors of Paris nous appartient (even if it gets cited as infrequently in Rivette’s filmographies as de Gregorio’s own performance in Straub-Huillet’s Othon gets cited in his). There are the interesting and varied ways of representing and evoking de Gregorio’s native Buenos Aires in absentia (in La mémoire courte, where it’s present only in documentary footage borrowed from coscreenwriter Edgardo Cozarinsky’s …; and in Tangos volés, where it’s entirely a matter of memory and pastiche) and perversely and dialectically shutting out most evidences of the city while actually filming there (in Corps perdus). There are three of Bulle Ogier’s most delicate and beautifully shaped performances, in Sérail, La mémoire courte, and Aspern. And finally, there’s the exhilaration as well as the heady vertigo of shuttling between eras and continents via what Tangos volés [see photo below] calls “la porte des songes” — a handy device for a nostalgic expatriate.