Written for the British Film Institute’s DVD release of this film in early 2011. — J.R.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to call A Hen in the Wind (1948) one of the more neglected films of Yasujiro Ozu, especially within the English-speaking world. Made immediately before one of his key masterpieces, Late Spring (1949), it has quite understandably been treated as a lesser work, but its strengths and points of interest deserve a lot more attention than they’ve received. It isn’t discussed in Noël Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema (1979) or even mentioned in Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema under the American Occupation, 1945-1952 (1992), the English-language study where it would appear to be most relevant. Although it isn’t skimped in David Bordwell’s Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (1988), its treatment in Donald Richie’s earlier Ozu (1974) is relatively brief and dismissive. It seems pertinent that even the film’s title, which I assume derives from some Japanese expression, has apparently never been explicated in English.

It may be an atypical feature for Ozu, but it is stylistically recognizable as his work from beginning to end, especially when it comes to poetic handling of setting (a dismal industrial slum in the eastern part of Tokyo, where the heroine rents a cramped upstairs room in a house) and its use of ellipsis in relation to the plot. Ozu himself was more than a little disparaging about it; Richie reports that a decade after its production and release, he wrote, ‘Well, everyone has his failures. There are all kinds of failures, however, and some of my failures I like. This film is a bad failure.’

Perhaps because the film testifies so powerfully to the fact and circumstances of Japan’s shattering defeat during the American Occupation, Ozu may not have been disposed to recognize its truths years later, during a sunnier period. By then, one should note, the film had been widely written off by others as a failure, and chided for its lack of verisimilitude in certain details (such as the cleanliness and tidiness of a room in a brothel), as well as its violations of certain norms associated with other Ozu pictures, especially his usual avoidance of violence. One hardly expects to witness a rape or brutal spousal abuse in an Ozu picture, and this film shows us both.

Tokiko (Kinuyo Tanaka) – a young wife and dressmaker with a sick child, in financial straits while her husband Shuichi (Shuji Sano) is away in the army – is forced into a night of prostitution by her son’s hospital expenses, and the plot charts the couple’s slow reconciliation after the husband returns and discovers what has happened. If we momentarily ignore the unusual constraints of the American censors during this period – which, according to Hirano’s book, required a line of dialogue in Late Spring to be changed from a statement that the daughter’s health had deteriorated ‘due to her work after being conscripted by the Navy during the war’ to ‘due to the forced work during the war’ – it’s tempting to hypothesise what other Japanese masters of this period might have done with the same basic story. If Akira Kurosawa had treated this subject, one would expect him to focus more on the husband’s war experience; Kenji Mizoguchi would likely have devoted more attention to the wife and her brief episode as a prostitute. Ozu, accepting the viewpoints of both wife and husband in turn, maintains a certain balance between them by showing us nothing of either the husband at war or the wife as a prostitute. Both of these essential elements are left up to our imaginations and the imaginations of the characters: we ‘see’ the husband at war through his wife’s sorrows at home, just as we ‘see’ the wife’s prostitution only through the husband’s visit to the bordello much later. Both unseen experiences are ultimately viewed as devastations that have to be accepted, digested, and ultimately worked through – although significantly, it is the single night of prostitution, not the much longer period of the husband at war, that the film addresses and focuses on.

Tokiko had to sell her own last kimono shortly before her little boy Hiroshi became ill, and had previously resisted the advice of Orie (Reiko Mizukami), the woman who purchased it, that she turn to prostitution. But once she finds it necessary to take Hiroshi to a hospital, she discovers he has an acute catarrh of the colon, and even though one of the nurses kindly offers her a handout, which she accepts, Tokiko concludes that she has to follow Orie’s suggestion in order to pay for the medical expenses, even without discussing the matter with her best friend, Akiko (Chieko Murata). She does this only once, with a single customer – an event kept off-screen, although we hear the customer complaining afterwards in the brothel that she wasn’t very good. Significantly, Ozu also keeps her confession of this act to her husband off-screen, and we learn about it only when she tells Akiko about it afterwards.

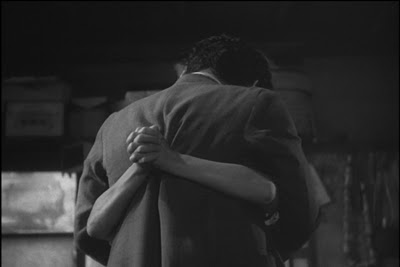

Shuichi becomes increasingly despondent about Tokiko’s revelation at his job, and back at home becomes obsessed with learning more, pumping his wife for information, including the location of the brothel, and then, after raping her (an event shown elliptically), going to the brothel himself, pretending at first to be a customer and quizzing Fusako (Chiyoko Fumiya), the 21-year-old sent to his room, about why she has succumbed to this profession. After leaving the brothel, he runs into Fusako again by chance and promises to find her another job. He tells a colleague, Kazuichiro (Chishu Ryu), also back from the war, who agrees to hire Fusako and urges him to forgive his wife just as he has forgiven Fusako; Shuichi accepts his advice on principal, but in fact is still in such a rage that when he eventually comes home he winds up shoving Tokiko down the stairs after she begs him not to leave again. But once he finally agrees to forgive and forget her transgression towards the end, it is her gesture of accepting him – her hands clasping one another behind his back – that seals their reconciliation, before Ozu ends the film with everyday exterior shots of the neighbourhood.

Despite the film’s chequered reputation, it has been persuasively defended by the two most influential and distinguished contemporary Japanese film critics, Tadao Sato and Shigehiko Hasumi, albeit in very different ways. Sato, who also observed that the brutal wife-beating in both A Hen in the Wind and The Munekata Sisters (1950) two years later were striking exceptions in Ozu’s work, has suggested, according to Bordwell’s summary of his argument, that ‘Tokiko’s becoming a prostitute symbolises a loss of national purity’ that was central to Japan’s sense of itself and its own spirit during the war:

Shuichi’s violence toward her becomes emblematic of the ingrained brutality of the war years, demonstrating that he has lost the noble purpose that had been used to justify the war. The film’s lesson, Sato concludes, cuts deeper than those contemporary films that sloughed blame off onto villainous militarists and weak-willed collaborators.(Bordwell, 302-303)

Supporting this theory is the fact that in the films of so many other countries under occupation or totalitarian rule, political issues, when they crop up at all, are commonly and covertly transposed into sexual issues. (Three examples of this tendency would be Henri-Georges Clouzot’s The Raven in France and Carl Dreyer’s Day of Wrath in Denmark, both in 1943, and Juan Antonio Bardem’s Calle Mayor/Main Street in Spain in 1956.)

In further support of Sato’s analysis is Ozu’s pungent and highly suggestive use of sordid settings – not merely the claustrophobic rented room, in a blocked corner of which the husband will rape his wife, but the stairs leading up to it from the ground floor, and, in a wasteland where the husband goes to brood, a large, gaping, exposed pipe, all of which contribute a great deal to the film’s emotional dynamics. And it is in this general arena – architecture, settings, the cutting between interiors and exteriors – that Hasumi’s own analysis of the film is especially illuminating.

Hasumi’s highly original 1983 book about Ozu, which lamentably isn’t yet available in English (I’ve read it in its French translation), addresses and responds to Sato’s defense of the film in some detail, agreeing that the film is ‘an important work,’ even though he concedes that ‘it is impossible to believe in Kinuyo Tanaka’s character,’ but focusing more on particular aspects of its unusual physicality. The film’s climactic moment of violence – conceivably the most shocking single moment in Ozu’s work – shows Shuichi shoving Tokiko down the flight of stairs and painfully shows us this moment frontally, from the foot of these stairs. Hasumi stresses the disturbing fact that Ozu focuses so often and repeatedly on this staircase long before this event happens, always from the same angle.

Part of the shock comes from Tokiko’s acceptance of her husband’s abuse, even to the point of masochism. (Her denial about what happened afterwards to her landlady, with the face-saving alibi that she had an accidental fall, is probably easier for most of us to understand, perhaps because we find this latter gesture more familiar.) But no less shocking is the fact that, as Hasumi points out, it is extremely rare for Ozu to show any stairs at all in any of his films; even when he implies their presence in various households, he almost invariably keeps them off-screen, Here he’s not only showing us a particular staircase countless times; he even prepares us for the climactic moment of violence in another way, by showing us an earlier scene in which Shuichi angrily kicks a tin can down those same steps and makes sure we hear the thuds as it hits every step.

Part of what makes Hasumi’s book so provocative is its way of countering and at times even contradicting most of the other critical studies of Ozu that we have. In response to the frequent claim that Ozu was the ‘most Japanese’ of Japanese filmmakers, Hasumi maintains that he may actually have been the least Japanese because of his (well-documented) obsession with Hollywood films, already evident in the movie posters seen in his features (including A Hen in the Wind, which has three of these in a single room). As a result of this fixation, Hasumi argues that even the weather in most of Ozu’s pictures is the weather of Southern California rather than that of Japan. And when it comes to the climactic moment of violence in A Hen in the Wind, Hasumi conjectures that this may have been inspired by Scarlett O’Hara’s fall down a staircase in Gone with the Wind (an accident that causes her miscarriage) – a film that Ozu saw in Singapore during the war, when he was viewing Hollywood films on virtually a daily basis.

It may seem paradoxical that Ozu’s strategies for conveying Japan’s sense of humiliation from the American occupation might have been drawn from the American cinema, but this possibility is supported by other things that we know about his taste. According to Richie, Citizen Kane was his favourite film; and he once famously remarked, ‘Watching Fantasia made me suspect that we were going to lose the war. These guys look like trouble, I thought.’

The film, in any case, is suffused with a sense of defeat, but it ends with some rays of hope, however characteristically elliptical Ozu makes their expression. Once Shuichi finally agrees to forgive and forget Tokiko’s transgression, it is significantly her gesture of accepting him – her hands clasping one another behind his back – that seals their reconciliation, before Ozu ends the film with everyday exterior shots of the neighbourhood.