From the Chicago Reader, April 21, 1995. It’s lamentable that, although Black Girl is now available on DVD from New Yorker, the color sequence in it appears in black and white. (In fact, I only saw this sequence in color for the first time when I showed this film in a course on world cinema of the 60s that I taught in Chicago in 2008.) To see this sequence in color, order the film’s BFI edition from Amazon UK. — J.R.

Black Girl

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Ousmane Sembène

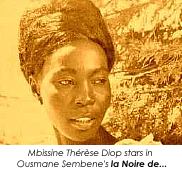

With Mbissine Thérèse Diop, Momar Nar Sene, Anne-Marie Jelinck, Robert Fontaine, Ibrahima Boy, and the voices of Toto Bissainthe, Robert Marcy, and Sophie Leclerc.

If you trace African film back to its first fiction feature, it is only 30 years old. Yet far from being underdeveloped, it begins on a more sophisticated level than any other cinema in the world. By some accounts Ousmane Sembène’s hour-long Black Girl was made in 1965, by others 1966, a characteristic ambiguity when it comes to African movies. Do you date them according to when they were made or when they were first shown? And given the scant and largely unreliable print sources that we have to check, how can we be sure about either date?

In any case, Black Girl is the only work from the 60s being shown at Columbia College’s first annual African Film Festival, a program of 16 features from six countries being shown this Friday and Saturday, free of charge. (Four films are from the 70s, seven from the 80s, and four from the 90s.) This festival is more important than you might assume, because practically none of the major works of African cinema are available on video and only a handful have ever opened in the U.S. Not counting Haile Gerima’s Sankofa (Gerima was born in Ethiopia but is based in this country), the last major African movie to open in Chicago was Sembène’s Guelwaar (1992), which premiered exactly a year ago (it’s also on the festival program).

Last April I reported erroneously that Sembène’s films were unavailable on video because his U.S. distributor, New Yorker Films, was reluctant to bring them out. A letter from Daniel Talbot, head of New Yorker, pointed out that the problem was ascribable not to him but to Sembène himself, who hates video and doesn’t like his films to be seen that way. Video tends to diminish and trivialize the force of a movie’s sound and image, so it’s not difficult to see how it would harm the political power and thrust of Sembène’s work. If you want to know why Sembène is one of the world’s greatest living filmmakers you have to see the evidence on film, and this weekend no less than five of his seven features are being screened — along with Souleymane Cissé’s even less often shown 1987 Brightness (Yeleen), my favorite African film, and Djibril Diop Mambety’s wholly remarkable Hyenas (1992), whose only previous showing here was at the Chicago International Film Festival.

I’ve seen only 6 of the 16 features being screened, and I can think of only a couple of my favorites that are missing, Mambety’s Touki Bouki (1973) and Cissé’s The Wind (1982). To all appearances, most of the best that the African cinema has to offer is being shown in one extended package, and though simultaneous screenings make it impossible to see everything, one can theoretically see all five of the Sembène films and Brightness.

One major reason for the sophistication of Black Girl is that by the time Sembène made it he was already in his early 40s and had published four novels and a collection of stories (including the story Black Girl is based on), studied filmmaking with Mark Donskoi at the Gorki studio in Moscow, and made three short films back in Africa (L’empire Sonhrai, Borom Sarret, and Niaye, all from the early 60s). By his own account, his main reason for becoming a filmmaker was that his stories could reach more Africans, especially those unable to read. (Illiteracy plays a key role in the plot of Black Girl.)

The story Black Girl is based on has the same French title as the film, “La noire de…,” which translates as “the black woman [or girl] of [or from, or belonging to]…,” conveying a good many additional connotations. The English translation of the story, included in the collection Tribal Scars, is called “The Promised Land,” and though the central plot of the story and the film are similar, the overall form and many of the details are not. In both an illiterate Senegalese woman from Dakar named Diouana, who’s hired as a servant by a white French couple living there with their young children, is thrilled when the wife proposes taking her with them to the French Riviera. But Diouana soon feels trapped, exploited, completely isolated, and depressed, and finally winds up slitting her own throat — an incident that’s recounted briefly on one of the back pages of a local newspaper. (Sembène’s story was reportedly inspired by just such an item in Nice-Matin.)

“The Promised Land” begins with the arrival of the police at the villa in Antibes where the suicide takes place, then flashes back to Dakar, freely shifting the narrative viewpoint between Diouana and her white mistress as it proceeds chronologically to the suicide. The story concludes with a poem, “Longing,” addressed to “Diouana, / Our sister,” in which the narrative voice becomes explicitly and exclusively African.

The film begins with Diouana’s arrival in France — where the family is staying in an ugly high rise rather than a villa — and gives us two separate flashbacks recounting her life in Dakar, before and after she’s hired by the French family. The narrative viewpoint is exclusively hers — she narrates much of the action, speaking petulantly to herself — up to the point of her suicide. Then, in a powerful coda, we see the French husband back in Dakar returning Diouana’s belongings to her mother — a sequence that can be described as both poetic and explicitly African in its thrust without duplicating anything in the original story’s poem. Other important differences between the story and film include Diouana’s age — close to 30 in the story, clearly much younger (though not explicitly stated) in the film — and the drunken old sailor of the story who tries to warn Diouana about France being more or less replaced in the film by a politically conscious young boy-friend, who has a picture of nationalist hero Patrice Lumumba on his wall and forebodings of his own. It’s worth noting that Senegal achieved full independence only in 1960; both Diouana’s glamorous dreams and her incapacities seem fully bound up in this fact.

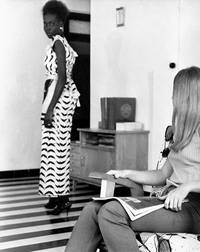

Considering Sembène’s passionate anticolonialism, it seems highly significant that Black Girl was made not because of but in spite of the Film Bureau created by the de Gaulle government’s Ministry of Cooperation in 1963 — an organization created to provide technical and financial resources to African filmmakers that began by assisting Sembène on Borom Sarret. In theory the Film Bureau couldn’t dictate the choice of subject matter by filmmakers it helped. Nevertheless it rejected Sembène’s script for Black Girl, because, as film historian Manthia Diawara puts it, “Sembène equated the way French Assistance Technique used cheap African labor to a new form of slavery.” (The sequence in which the heroine is selected by the French wife from a pool of African women on the street plainly evokes a slave market.) In other words, the story of Diouana’s disenchantment with her patrons had obvious bearing on the Film Bureau’s own patronage and patronizing attitudes. (Sembène’s hatred of charity and foreign aid as a form of postcolonial paternalism runs through his oeuvre; it forms an essential part of Guelwaar.)

To make his first feature Sembène ultimately had to turn to André Zwobada — an old friend and colleague of Jean Renoir’s who, back in the 30s, helped write Renoir’s Communist documentary La vie est à nous and was assistant director on The Rules of the Game. In the 60s Zwobada was the main editor for the French government’s newsreel service Actualités Françaises; sharing Sembène’s contempt for the paternalism of the Film Bureau, he wound up producing Black Girl and arranging for its postproduction to be done at the Actualités Françaises facilities in France. (Thanks to this arrangement, many of the film’s actors — all of them wonderfully precise and believable nonprofessionals — are dubbed by others; Sembène himself appears briefly in a couple of scenes as a schoolteacher, smoking his pipe.)

Ironically, the Film Bureau wound up purchasing the noncommercial distribution rights to Black Girl after it was made — seeking to control its distribution after failing to stifle its production. Broadly speaking, this all sounds like the African/French version of Sundance and Miramax: buy up, promote, and thereby contain the independents, especially the feistier ones who spit in your face. This is also the implication of Lizbeth Malkmus and Roy Armes’s tentative suggestion, in their recent book Arab & African Film Making, that the 60-minute running time of Black Girl may be the consequence of some requirement of the original distributors; the film reportedly once had a color sequence detailing Diouana’s “first reactions to France.”

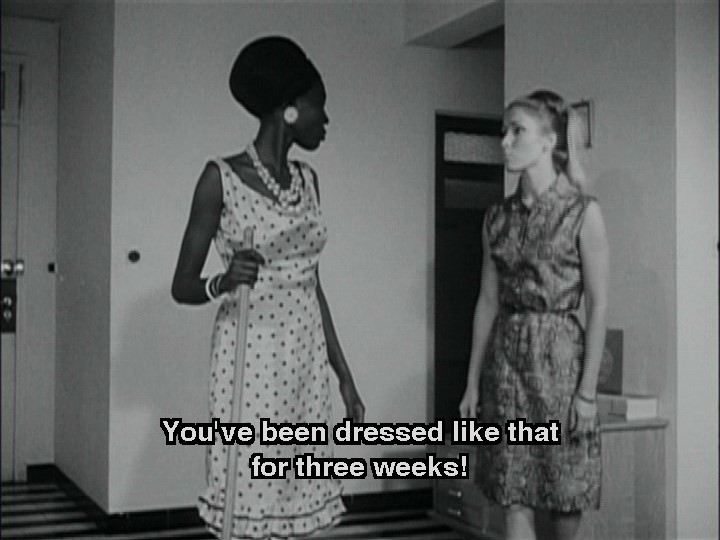

But the extraordinary thing about the film’s black-and-white cinematography is how essential Sembène makes it — formally, thematically, and even semantically — to the story he has to tell. As another critic — Lieve Spass, writing in the magazine Jump Cut — has pointed out, “Diouana wears a white dress with black dots; her suitcase is black; the apartment seems entirely in a black/white color scheme; the food prepared falls into the same categories — black coffee, sterilized milk, white rice; even the whiskey consumed generously by the Frenchman bears the label ‘Black and White'” — an opposition “enacted most dramatically when the camera focuses on Diouana’s inert black body in the white bathtub,” and one that’s matched by the movie’s striking juxtaposition of French music (barrelhouse piano evoking Shoot the Piano Player) and African music (instrumental as well as vocal) on the sound track.

Indeed, both the black-and-white cinematography and the music display an almost brutal concentration and economy that are basic to the film’s style and meaning; they uncannily get us to share the naïve consciousness of Diouana as it blooms or withers in different spaces — buoyant and freewheeling in the streets of Dakar when she learns she’s going to France, aggrieved and constricted in the Antibes apartment that encompasses nearly all of the France she sees. Though critics like Diawara, Malkmus, and Armes habitually describe Sembène as a social realist, it’s hard to think of any other artist pegged with that moldy label who’s so intimately and poetically concerned with what freedom and oppression actually feel like, not simply what they consist of. And if Sembène is in fact a social realist, he must be a pretty weird one to strip his plot to such emotional and poetic basics that we can’t walk away from this movie with the usual basic data. We don’t even know where the French family’s home base is, and we know next to nothing about Diouana’s past and family — it’s not even clear whether the little boy associated with her in Dakar is a friend, acquaintance, or brother. But we’re not persuaded that any of this information matters in the slightest. By the same token, I’m fully convinced that nothing in this movie can be weakened or spoiled by knowing the story in advance, which is why I’m not showing any hesitation about revealing it. For Sembène, the event is mere raw material; articulation is everything.

In fact, the intensity of everyday experience captured through a minimalist “newsreel” palette of New Wave shooting (natural lighting, hand-held camera movements) and postsynced sound is precisely what lifts this movie well beyond the limits of a simple tract. We share Diouana’s giddy pleasure as she circles her neighbors telling them the news of her job and as she, to the grim disapproval of her boyfriend, skips barefoot over a colonialist war memorial in downtown Dakar labeled For Our Dead, a Grateful Nation — just as we share her subsequent humiliation in Antibes when her first letter from her mother, consisting mainly of reprimands, is read aloud to her by the French husband, who then proceeds to compose her “reply” in his own words when she fails to provide him with any. In all three cases Diouana’s naïveté and ignorance are central to the scene’s meaning, but Sembène refuses to allow any cozy feelings of superiority — on our part or his. He also manages to work in plenty of irony regarding her boyfriend’s seriousness about the war memorial and her employers’ insensitivity about her illiteracy — without simply indicting them either. Everyone is criticized, but no one is stereotyped. When the French wife objects to Diouana wearing high heels in the apartment and Diouana responds by dropping them off in the center of the living-room carpet, the silliness and sadness of both characters registers with equal intensity. There’s a similar pathos in the husband’s efforts to assuage Diouana’s misery with wads of money. For all the simplicity of the materials and the fablelike aspects of the story, a complex and passionate intelligence is shaping the meaning in every scene.

I’m an amateur when it comes to African aesthetics — in large part because I have the disadvantage of knowing them mainly secondhand through such outsiders as Jean Rouch and John Coltrane. Yet it seems to me that they may have something to do with a certain freedom from conceptual rigidity. It is this that allows Sembène to shift in “The Promised Land” between the viewpoints of mistress and servant and between the forms of prose and poetry and in Black Girl to get us to share the consciousness of a single alienated character and then to create his most awesome emotional impact and summary statement after her death, when that consciousness is no longer present. He achieves this through one of the most basic artifacts and symbols in African aesthetics, a mask — a key object, I should add, that plays no part at all in “The Promised Land.”

Shortly after Diouana is hired by the French family in Dakar, she buys the mask from the little boy to present to them as a gift; they already have two or three others, so it’s merely an addition to their collection (as she is). The mask appears again at the tail end of the second flashback, after we see her in bed with her boyfriend — a detail that places this scene before the presentation of the gift in the first flashback (another example of Sembène’s freedom from conceptual rigidity). When Diouana is in the depths of her depression in Antibes and starts to pack her suitcase she angrily takes the mask back, occasioning a fight with the wife for possession of it that the husband settles in Diouana’s favor.

Finally, the husband brings both Diouana’s suitcase and the mask back to her mother in Dakar and attempts to ply her with francs; the mother simply walks away from him, refusing his guilt-ridden moral bribery. But the boy silently reclaims the mask and, putting it on, tracks the husband back to his car, provoking his paranoia all the way. After the husband drives away, the boy, facing the camera, removes the mask, and the movie ends. There are few endings in all of cinema as powerful and rich as this — brimming with tragic wisdom and latent meaning, with finality and promise, with humor and pain. Diouana and Africa and the mask and the boy have finally become one, an indissoluble and unbearable human fact staring us all in the face. It’s at this point that African cinema begins.