From the Chicago Reader (January 5, 1990). — J.R.

As a moviegoer who was privileged to see a good many films, both new and old, in a number of contexts, places, and formats in 1989, I can’t say it was a bad year for me at all. I saw two incontestably great films at the Rotterdam film festival (Jacques Rivette’s Out 1: Noli me tangere and Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan’s A Story of the Wind), and several uncommonly good ones both there and at the festivals in Berlin, Toronto, and Chicago. (Istvan Darday and Gyorgyu Szalai’s The Documentator and Jane Campion’s Sweetie — the latter due to be released in the U.S. early this year–are particular standouts.) Thanks to the increasing availability of older films on video, I was able to catch up with certain major works that I’d missed and see many others that I already cherished.

But considering only the movies that played theatrically for the first time in Chicago, I have to admit that it was a discouraging year. In fact, 1989 was the worst year for movies that I can remember, particularly when it comes to U.S. releases. Gifted filmmakers are granted less and less freedom as the Hollywood studios are taken over by conglomerates and European films are set up as international coproductions — both trends that have been in process for some time now; and the grim consequences of these changes become much more apparent when one takes a long backward look rather than when one considers the immediate surface effects of movies on a week-by-week basis.

When it comes to good films, this past year had plenty to offer, but great films were few and far between, and all but a precious few of the best that showed in Chicago were American and English independent productions. This wasn’t true in 1987 and 1988, when my ten-best lists included films from Africa, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, the Soviet Union, and the People’s Republic of China. Judging from what I’ve seen at festivals, I suspect that the difference has as much to do with the shrinking number of foreign-language imports to this country as with the overall quality of films in other countries. I should hasten to add, however, that apart from a few exciting glimmers from the Third World in the late 80s and a discernible resurgence in Great Britain, world cinema as a whole appears to be going through a period of desperate retreads, equivocal floundering, and outright exhaustion.

I certainly don’t rule out the possibility that important and exciting things are happening in cinema that we still know nothing about. The distressing lack of communication in the English-speaking world about new work not sanctioned by the film industry has been exacerbated in recent years by the absence of a single film magazine in English that can be relied upon to impart this information on any regular basis. Indeed, the best films around usually turn out to be well-kept secrets; with the striking exceptions of Do the Right Thing and sex, lies, and videotape — two American independent features that managed to make it into the big time — the best movies of the year tended to be either overlooked or underdiscussed.

In the list below, I’ve excluded contenders that showed at the Chicago Film Festival in 1989 and are scheduled to open commercially in 1990, such as Maurizio Nichetti’s The Icicle Thief and Michael Moore’s Roger and Me. Alas, Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Decalogue still lacks a U.S. distributor, and given all the obstacles to acquiring one — the unwieldiness of a ten-part work, a reportedly recalcitrant agent in charge of the North American rights, the displeasure exhibited by the New York Times toward the Decalogue segment A Short Film About Killing, the difficulty of imagining a Kieslowski segment on Entertainment Tonight — we unfortunately can’t count on it turning up in the foreseeable future.

Before proceeding with my list, I should stress that I chose films that I think are likely to last, and my criteria for determining this largely have to do with how certain films registered on repeated viewings. In the case of High Hopes (I was able to see the film only once), this is basically a matter of guesswork; by the same token, it’s theoretically possible that certain other films I saw only once — including Bangkok Bahrain, Damnation [see above], Kung Fu Master!, Leola, Little Vera, The Long Weekend (O’Despair), Macao, The Peddler, Queen of Hearts, and To Kill a Priest — might have made it onto the list if I’d seen them a second time.

1. Distant Voices, Still Lives

To the best of my knowledge, this is the only film released in the U.S. in 1989 other than The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (see below) that has a reasonable chance of being considered a great work ten years from now. It is the only one that rethinks the cinema from the ground up, starting from scratch — perhaps because it also happens to be the only one that appears to have been made solely out of personal necessity. Grounded in family memories, Terence Davies’s achronological account of life in Liverpool in the 40s and 50s, structured more on feelings than ideas, relies mainly on portraiture and collectively experienced songs for its power.

Most art films scare audiences away because of their intellectual content or their exotic subject matter, but this masterpiece has neither, and apart from its lack of stars, I don’t know how it can be considered any less accessible than, say, Rain Man; indeed, in terms of raw impact, I can’t see any Hollywood release this year coming within miles of it.

I suspect it was largely the relative absence of plot — plot being the ne plus ultra of commercial filmmaking — that deprived this movie of most of the audience it could and should have had. At the same time, however, this absence gives a wholeness and intensity to every moment that is virtually impossible to achieve in narrative filmmaking, which tends to sacrifice such expressive possibilities for the sake of conventional continuity. And despite the fact that violence and emotional pain form part of this intensity — leading some viewers to confuse this part with the whole and conclude that the film is a “downer” — the pleasure and sheer empowerment offered by the songs and collective gatherings are certainly no less prominent or vibrant. I can honestly say that no movie this year gave me more happiness.

2. A Short Film About Love

Having seen only half of Kieslowski’s Decalogue at this point, I’ve selected the best of the five parts that I’m familiar with, and one of the two parts — along with A Short Film About Killing, which I’ve also seen — that was expanded by its director to a feature-length running time, which is the version that I saw. In keeping with the generally ambiguous relationship of the Decalogue to the Ten Commandments, this part relates to the commandment “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” though neither of the major characters is married.

Like the other self-sufficient installments in the Decalogue that I’ve seen, A Short Film About Love is in fact centrally concerned with a highly sophisticated moral ambiguity — a distinguishing trait of the contemporary Polish cinema that could also be noted this year in Agnieszka Holland’s flawed but powerful To Kill a Priest as well as Andrzej Kotkowski’s Citizen P. Unlike the first-grade ethics of a Crimes and Misdemeanors, which can’t see beyond either the notion of good guys versus bad guys or the self-absorption of the three characters it is ostensibly attacking, Kieslowski and Holland are interested in the complex intricacies — the paradoxes, contradictions, and cross-purposes — that figure in ethical choices.

The plot of A Short Film About Love centers on the voyeuristic relationship between a young and solitary postal worker (Olaf Lubaszenko) and an attractive and promiscuous older woman (Grazyna Szapolowska) who live in facing flats in a high-rise complex. The story develops through a network of subjective camera angles, each character gradually becoming aware of the other, that recalls the elliptical story telling of Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But where Hitchcock’s film restricted its viewpoint to that of the voyeur, Kieslowski’s story reveals the partial and developing viewpoints of both characters as they diverge and coincide. The story begins from the viewpoint of the postal worker, and proceeds in that manner until the two characters meet — in a highly charged and traumatic sexual confrontation that leads to the hero’s suicide attempt. Then the woman’s viewpoint takes over, and her own increased understanding of the obsessive and repressed voyeur takes hold when she can look through his telescope and imagine both what he saw and how he saw it. For its immaculately controlled story telling and performances, Kieslowski’s parable provides as much of a model of putting all the elements in a work to use as the Davies film does, although here the interest is in character and plot rather than the distillation of memory.

3. The Adventures of Baron Munchausen

It seems that nearly everyone seriously underrated this picture, myself included — which became apparent to me when I went back for a second look several weeks after it opened. The audacity of Terry Gilliam’s unorthodox narrative structure and the imaginative eclecticism of individual scenes seemed to give a good many viewers more than they knew what to do with, although I should add that grown-ups seemed to have more problems with this overload of invention than kids did, judging from a weekend matinee I attended. The intellectual and emotional coherence of the picture’s design grows as one becomes more familiar with its details, although unfortunately most critics were too alienated by their initial impressions to dig any further. As a consequence, an inordinate number of reviewers treated this film, like Ishtar a couple of years ago, less as a work of art than as a financial investment, and wound up siding with the investors — a peculiar and rather sinister vantage point for a noninvestor to take toward any movie, but one that seems to be gaining popularity among critics.

Although the European responses to this grand fantasy spectacle were generally no more enthusiastic than the American ones, it’s worth noting that the major sources of and counterparts to Gilliam’s visions are European — Georges Melies (a conscious influence), Lewis Carroll, and Italo Calvino are the first that spring to mind. Gilliam’s imaginative freedom in relation to both space and time gives this movie a kind of richness that goes far beyond the scenic tapestries of Fellini and animated Disney features, and while The Adventures of Baron Munchausen may not have the same credentials as The Wizard of Oz or the 1940 version of The Thief of Bagdad as a freewheeling fantasy entertainment, its metaphysical and visionary scope is even broader. Whether or not the film finally qualifies as a magnificent “failure” — the conclusion I reached in my original review — is a judgment that can only be made after we come to know the picture better in the years to come; in the meantime, there’s no question that it deserves the attention needed to make such an evaluation.

4. Do the Right Thing

Practically the only American movie this year that stimulated extended, in-depth discussion about anything other than just movies, Spike Lee’s energetic portrait of a day in the life of the inhabitants of a Bedford-Stuyvesant block breaks with the Hollywood mainstream by doing away with the moral certainties represented by heroes and villains. In addition to representing a quantum leap over Lee’s previous features, this highly entertaining and provocative feature addresses contemporary racial issues in a manner that startlingly respects the ability of viewers to think for themselves.

In contrast to the stacked decks that generally accompany most Hollywood “problem” pictures, which typically divvy up the antagonists in racial conflicts into separate piles labeled “us” and “them,” Do the Right Thing discovers a way of addressing a varied audience in such a way that no single viewpoint provides a skeleton key for comprehending the action in all its implications. The motto of Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, “Everyone has his reasons,” applies here not only to the separate perspectives of the pizzeria owner (Danny Aiello), his delivery boy (Lee), his two sons (Richard Edson, John Turturro), three alienated malcontents (Giancarlo Esposito, Bill Nunn, Roger Guenveur Smith), two elderly outsiders (Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis), and three comic kibitzers (Robin Harris, Frankie Faison, Paul Benjamin), among others, but also to the separate legacies of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X that are evoked at the movie’s end. Theoretical pluralism has often played a substantial role in American movies, but genuine pluralism pushed so far that it actively determines narrative structure is a rarity, and Lee’s comedy-drama provides a bracing model for how this can be done.

5. High Hopes

Like Do the Right Thing, this English comedy-drama by Mike Leigh can be regarded as an up-to-date news bulletin from an embattled community; but while Lee’s community constitutes little more than a single city block, Leigh’s implicitly takes in an entire nation. One can’t argue that the film’s small cross-section of Londoners living in Thatcher England is seen with the same pluralism and generosity that Lee brings to his own complex of characters. On the contrary, the film’s heart and mind clearly belong with its disenfranchised working-class couple, Cyril (Philip Davis) and Shirley (Ruth Sheen) — a lovable pair whose viewpoint provides the movie’s moral center, for better and for worse — and the characters outside their class tend to be caricatured with increasing ferocity the farther one moves up the economic ladder. No one could dispute, however, that High Hopes is a film with a great deal of heart and soul, and its polemical view of contemporary life in England certainly carries a great deal of conviction. (The only American movie this year with a comparable political bite, Bob Balaban’s underrated and stylistically remarkable Parents, significantly had to go back to the 50s to make many of its major points, and then unfortunately dissipated some of these ideas in horror-movie conventions.)

A well-known stage, TV, and film director in England who is still virtually unknown outside his home turf, Leigh has worked out a collective method of generating both characters and stories with the input of his actors that has few counterparts in this country (although the mature work of the late John Cassavetes has frequently been misread as similarly improvisational). Because he has honed this technique over many years, the results in High Hopes have none of the slapdash quality that one might expect; the parallels established between various characters and scenes have a pointed rigor that makes virtually every fleeting moment functional. Given the relative success of High Hopes as an art-house picture in the U.S., it would be heartening if this could lead to an opportunity to see some of Leigh’s previous work — his earlier feature (Bleak Moments, made in 1971) and his dozen or so TV plays.

6. Golub

The only documentary in this list is a 58-minute portrait of the New York painter Leon Golub by the Chicago-based Kartemquin collective, directed by Jerry Blumenthal and Gordon Quinn. In the past, Kartemquin has mainly concentrated on grass-roots political struggles; profiling here a political painter, they come up with an exemplary approach to the vexing problem of how to present artists and artists’ works on film. In place of art critics and other “experts,” we get ordinary viewers and Golub himself commenting on the work and its meanings. Instead of treating the moment when a painting is completed with hushed reverence by isolating it as a “finished” work in an artist’s studio, the film moves directly from its creation to its social reception, without missing a beat. And because Golub himself is an unusually articulate and self-aware commentator on his own work, the film’s step-by-step chronicle of the execution and impact of one of his paintings offers a model of purposeful exposition.

7. Rembrandt Laughing

The ninth feature of Jon Jost, the most conspicuously neglected of talented American independents, represents a new level of achievement in his work, and one suggesting certain parallels with Mike Leigh–an improvisational method of working with actors as well as a concentration on the textures of everyday life. Less politically oriented than most of Jost’s other features, this elliptical account of a little over a year in the lives of a few friends in San Francisco has a spiritual dimension that is also relatively new to Jost. As story telling, the film has its awkward moments, and there is one unfortunate sequence involving gangsters that is downright inept; but as visual poetry rendered with feeling, lyricism, and a great deal of camera virtuosity, the film remains firmly fixed in my memory.

8. sex, lies, and videotape Like my ninth and tenth choices, this is a first feature by an American writer-director that constitutes an impressive debut. As other commentators have noted, Steven Soderbergh shows more originality at this point as a writer than as a director. Although his handling of his talented cast — Andie MacDowell, James Spader, Laura San Giacomo, and Peter Gallagher — is certainly accomplished, the best that can be said for his basically conventional mise en scene is that it admirably serves his actors and dialogue without adding anything very significant to them.

When I met Soderbergh at the Denver film festival three months ago, I was impressed by his modesty in spite of the avalanche of prizes and rave reviews that have been showered on him. (He was in Denver, in fact, to pick up still another prize, the John Cassavetes Award.) Still in his mid-20s, and uncommonly serious and self-critical for someone so exalted, he comes across as a filmmaker who feels that he still has a lot to learn — an education that we can only look forward to sharing and benefiting from.

9. Forevermore: Biography of a Leach Lord

The most intriguing discovery of Barbara Scharres’s “Films From the Lunatic Fringe” series at the Film Center in September was this independent first feature by Erik Saks — a Los Angeles environmentalist who is roughly the same age as Soderbergh — a pseudodocumentary about the life of a fictional toxic-waste dumper set between the 1940s and the ’90s. Using an achronological narrative structure and a dry, poetic offscreen narration, the film conveys a lot of information about the damage that is routinely done to our environment. By locating this concern in one man’s biography — his troubled family life as well as his profession — Saks sets up a dense network of affects and significations, and the subject becomes not merely the ruin of a landscape but the erosion of a consciousness — and beyond that, the multiple ways in which landscape and consciousness interact. (As a former student of James Benning — who works in a related tradition, and who appears briefly in Forevermore — Saks shows himself to be an astute and original pupil.)

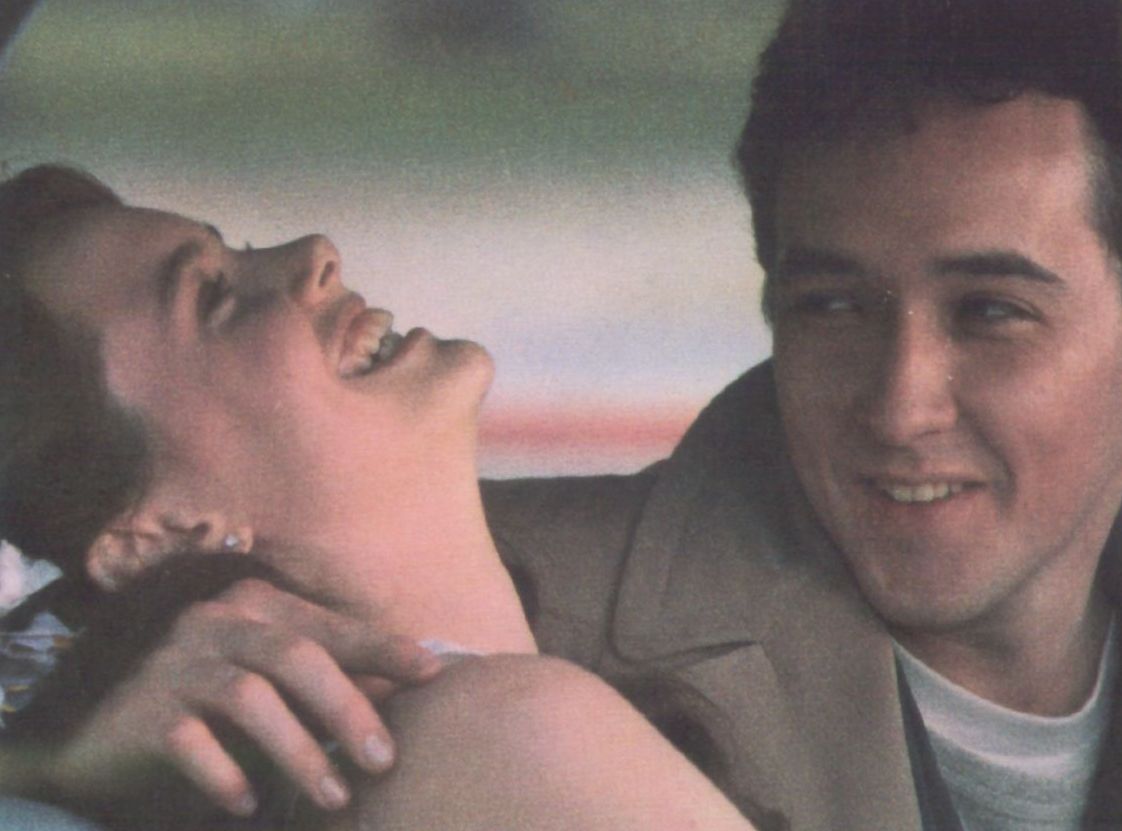

10. Say Anything . . .

When I recently had occasion to cite Cameron Crowe’s tender love story as one of the best Hollywood features of the year to a group of students at Cornell, a freshman countered that, being the same age as the two leads (John Cusack and Ione Skye), she thought that the movie bore no relation to her own experience. Assuming that her reactions were shared by her contemporaries, this may account for the lukewarm box-office response to what was clearly the freshest and sweetest youth movie of the year. It’s possible, in other words, that older critics like myself were so enchanted by the film’s distance from the cliches and conventions of recent teen movies that we confused this distinction with realism.

Realistic or not, Crowe’s assured script and direction, the performances of Cusack, Skye, and John Mahoney (as the heroine’s father), and the meticulous production design all made this a very touching movie that, as LA colleague David Ehrenstein pointed out to me, is probably as close as the recent American cinema can get to early Truffaut. (For that matter, judging by Claude Miller’s The Little Thief, this may be even closer than recent French cinema gets to early Truffaut.) The budding romance between an isolated and accomplished biochemistry student (Skye) and a devoted but otherwise diffident jock (Cusack), complicated by the girl’s intense relationship with her father, was notable mainly for the sustained interest and delight it showed in its characters; whether or not one considers them “believable,” Crowe certainly filled them with energy and life.

As indicated above, the number of good movies this year was as plentiful as the number of great movies was minuscule, and I can think of at least two dozen runners up to add to the titles already mentioned. These are, in alphabetical order, The Abyss (before the plot went gaga), Apartment Zero, Ashik Kerib (a minor work by a major filmmaker), The Big Picture, Dangerous Liaisons (which I underrated), Drugstore Cowboy, A Dry White Season, The Fabulous Baker Boys, Family Viewing, Four Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle, Henry V, Kung Fu Master!, “Life Lessons” (the Martin Scorsese episode in New York Stories), Mapantsula, Mr. Freedom, “Oedipus Wrecks” (the Woody Allen episode in New York Stories), Poulet au vinaigre, Scandal, She-Devil, Surname Viet Given Name Nam (in spite of all its difficulties), Tales From the Gimli Hospital, The War of the Roses, A Winter Tan, and, to end with a comedy that was both overhyped and underrated, Young Einstein.

Special mention should be made of the excellent restoration of Lawrence of Arabia, a rousing good spectacle that would have certainly made it onto this year’s ten-best list if it had been made today rather than in 1962. (For all my ambivalence about the ultimate value of David Lean’s undeniable skills as a tasteful literary director, if there ever was a case to be made for their importance, Lawrence clearly makes that case.)

But when it comes to granting the F.W. Murnau Award — given each year to a new or old film that provokes a radical revision in our sense of film history — I can think of an even greater blockbuster that was impeccably restored, a movie that surfaced in Chicago over two evenings at the Music Box in March: Fritz Lang’s The Nibelungen (1924), a mind-boggling silent German epic that was shown with Gottfried Huppertz’s powerful original orchestral score performed by Dennis James on the organ.

The restoration and presentation of this masterpiece by Enno Patalas of the Munich Film Museum — who has been carrying out comparable work on other early Lang films, as well as silent films by Murnau and Lubitsch — were exemplary in every sense of the word, including the use of adjacent slides to translate the beautifully drawn and pictorial intertitles that subtitles would have obscured. The major revelation for me about this version of the 13th-century German legend is how much of the cinema to come is already contained in–and clearly derives from–Lang’s magisterially composed images: movies as diverse as The Blue Light, Flash Gordon, Alexander Nevsky, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, a slew of classic westerns, Throne of Blood, Star Wars, and The Emerald Forest, among many others, would all be unthinkable without this wondrous classic. (One might even postulate a possible influence of Walter Ruttmann’s beautiful animated dream sequence on the abstract animated shorts of Oskar Fischinger in the 20s and 30s.)

It’s worth noting that this luminous, well-attended event took place in all its splendor only in Chicago; the screenings of The Nibelungen in Los Angeles and New York had to do without the Huppertz score, which to my mind is an essential part of the work. It was the finest single film event that I’ve ever attended in Chicago (although James Bond’s heroic screenings of Days of Heaven and 2001: A Space Odyssey in 70-millimeter in Lincoln Park last summer, the latter in a driving rain, certainly deserve to be applauded); if any of the Hollywood studios had come up with a movie event that was even one-tenth as impressive, it might not have been such a lackluster year.